This curriculum unit, designed for a high school English class, examines the importance of protest music during the Civil Rights movement and how music has changed and reshaped itself into protest anthems for the #BlackLivesMatter movement of the 21st century. Beginning with the importance of protest songs in the 1950s and 60s during Civil Rights campaigns including sit-ins, marches, and boycotts, students will examine how music provided the soundtrack for social change. As the unit progresses, they will analyze how that soundtrack has changed over the years, and will analyze the similarities and differences between protest music then and now. Standards covered include literacy, especially in informational texts; writing for varied purposes, including explanatory and argumentative tasks; and integration of multiple sources in research and presentation. Key objectives for this unit are that students will identify similarities and differences between musical styles and messages (i.e. Underground Railroad spirituals and Civil Rights protest songs), and the repurposing of songs for protest purposes; and that students will analyze contemporary music associated with the Black Lives Matter movement for similarities and differences to previous protest music (i.e. Civil Rights and Black Panther Party era music).

Protest music – the soundtrack of social change – has changed and shifted over time. This unit investigates and examines how the genre of protest music has shifted from the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s to the Black Lives Matter movement of today. In what ways has the social contract of music and musicians been redeveloped and renegotiated in the face of the technology boom of the last 20 years? How does written literature follow and/or diverge from the paths taken by music over the last 50-60 years? Many of the Civil Rights era songs of protest grew out of old Negro spirituals and the call-and-response traditions of African American culture. The Black Lives Matter movement, however, seems less grounded in those traditions, and its musical voice is instead largely found in rap and hip hop music. Does this change its accessibility or appeal? Does the music of BLM serve as an invitation or a barrier to older generations? Was there a musical genre that acted as a ‘bridge’ between the protest music of the 50s and 60s and the BLM-grounded music of today? What elements of musical genre identity were gained or lost in the transition, and how has that affected the efficacy of the musical genre’s identity. Examining the changes that musical genres experience in their identities not only provides challenging and relevant reading and discussion for students in class, but also acts as a catalyst for deeper conversations about how students’ identities also grow and change as their age and experience grows and changes. By using musical identity as a framework, students will be able to articulate and define the changes they have experienced – and especially for teenagers – are experiencing in their individual identities, and how these changes sometimes lead to conflict and dissonance in their relationships with people (family, friends) and institutions (work, religious organizations, schools). Although such affective concerns may not be explicitly described in Pennsylvania’s curricular standards, they are critically important in educating adolescents for productive citizenship. By exploring how musical genres have self-identified, self-perpetuated, and evolved and changed over time, I hope to help students see that that trend is consonant throughout all art forms – visual arts, literary arts, and performance arts – and that it is true for the ‘art’ of being human, as well. We change and grow; embrace new identities and discard outdated ones; consistently over time, and this is reflected in our creations. I hope, then, to help students to be more cognizant of the arc of human history and development, specifically as it’s expressed in music, art, and literature, in order to help them both see patterns, and to see a place for themselves and their own creations in our current historical moment. Werner (2006) writes, History never happens in straight lines. The lines connecting events extend across space and time in tangled, irreducible patterns. All forms of storytelling oversimplify the patterns, but music simplifies less than most. Structurally, music mirrors the complications of history. Moving forward through time, music immerses us in a narrative flow, gives us a sense of how what happened yesterday shapes what’s happening now. But the simultaneous quality of music – its ability to make us aware of the many voices sounding at a single moment – adds another dimension to our sense of the world (xiii-xiv). This unit, then, seeks to help students untangle both elements of their personal histories, and those in our shared history, in order to identify “how what happened yesterday shapes what’s happening now” for us as individuals in a society, and for our society as a whole. “All I ever had, redemption songs” (from “Redemption Song” by Bob Marley) In 1963, LeRoi Jones, in his now classic text, Blues people: Negro music in white America, writes: “It seems possible to me that some kind of graph could be set up using samples of Negro music proper to whatever moment of the Negro’s social history was selected, and that in each grouping of songs a certain frequency of reference could pretty well determine his social, economic, and psychological states at that particular period” (65). Later, he adds, “the most expressive Negro music of any given period will be an exact reflection of what the Negro himself is. It will be a portrait of the Negro in America at that particular time” (Jones, 1963, 137). African American history is fraught with conflict and oppression, and yet, out of the horrors of slavery and the atrocities of Jim Crow laws and lynchings, music emerged as a constant force, held in tension with, and against, the worst historical moments as an enduring and creative force – a call to action, a salve for healing, a balm for grief, and a companion in suffering. Taking Jones’ words as a map, it is, in fact, possible to align African American history, in both its tragedies and triumphs, with the music created alongside it. Slave Songs to Gospel Hymns – “Follow the Drinking Gourd” Although this unit will not spend time tracing the development of the African American spiritual from slave songs through gospel hymns, it is worth noting, and sharing with students, that even in the 18th century, enslaved Africans used music to resist, to persist, and to survive. Forced to give up their language, religion, and culture, enslaved men and women in the American South adopted the hymns they were often forced to learn by their ‘Christian’ owners and adapted them to suit their own purposes, infusing them with beats and rhythms reminiscent of the music from their native lands. Thus, songs like “Follow the Drinking Gourd” and “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” became private code that could be publicly sung to announce plans to escape slavery and run to the North and the possibility of freedom. This early example of music’s adaptability to cultural identity and usefulness as a tool of protest can set the foundation for students’ learning in this unit. The Blues – “I’m a Man . . . M – A – N . . .no B – O – Y” (“Mannish Boy” by Muddy Waters) While African Americans experienced a brief taste of freedom and the benefits of US citizenship during Reconstruction, the South pushed back hard after the so-called Northern carpetbaggers returned home, instituting brutal policies designed to return Black southerners to slavery-era status by enforcing Black Codes and Jim Crow laws, creating a fully segregated society, with swift and often lethal retaliation for any perceived violation of the Southern social structure. Music reflected this change in the birth of the blues, a musical genre that expressed the fullness of the struggle, and allowed people to acknowledge the weight of the burden they were carrying, and to lighten the load a little in the sharing of that burden through song. For Ralph Ellison, the blues present a philosophy of life, a three-step process that can be used by painters, dancers, or writers as well as musicians. The process consists of (1) fingering the jagged grain of your brutal experience; (2) finding a near-tragic, near-comic voice to express that experience; and (3) reaffirming your existence. The first two steps run parallel to the gospel impulse’s determination to bear witness to the reality of the burden. But where gospel holds out the hope that things will change, that there’s a better world coming, the blues settle for making it through the night” (Werner, 2006, 69-70). The blues, then, represents a musical style that understands that life is hard, and accepts that it might not get better. It affirms, however, the dignity and valor of persisting in the struggle, even without a promise of a better tomorrow. If the old slavery-era spirituals laid the foundation for protest music, then blues music built the scaffolding, creating a structure upon which to build a music crafted specifically for resistance. Jazz – “My only sin is my skin” (“What did I do to be so black and blue?” by Louis Armstrong) While the blues was largely the domain of African American musicians alone, the birth of jazz brought Black and White musicians together in new ways, further laying the groundwork for the Civil Rights movement and its music. The popularity of jazz, and its ability to draw in multiracial audiences, offered its marquis players an element – albeit a small one – of leverage in negotiating recording contracts and performance venues. This enabled Duke Ellington, for example, to stipulate in his contracts that he would not play for segregated audiences (Verity, 2017). White bandleader Benny Goodman integrated his jazz ensemble, the first bandleader to do so, although it was against the law in some Southern states for Whites and Blacks to play together (Verity, 2017). One note, one lyric, one recording, one performance at a time, music was pushing people together. Prompted by decades of oppression and countless acts of racist aggression on micro and macro levels, the Civil Rights movement found its footing in the mid 1950s, and began its inexorable march to freedom by the early 1960s. Music was, both incidentally and intentionally, a critical component of the Movement’s growth and persistence. Gospel Influence – “I’ve been buked and I’ve been scorned” (Mahalia Jackson) Perhaps because so many of the Movement’s leaders were active in their church congregations, or perhaps because those early resistance songs – the old spirituals – still lived in churches, gospel was the first musical standard bearer in the Civil Rights movement. Whether by recontextualizing time-honored gospel lyrics, or by reinterpreting their rhythms, gospel singers brought the weight of the historical moment together with the weight of their sacred songs to create powerful anthems that mobilized and encouraged Civil Rights workers in sit-ins, through boycotts, and on marches. While countless gospel singers recorded and performed the songs that would guide and shape the Movement, perhaps none were more central than Mahalia Jackson. Werner (2006) writes that It wasn’t just Mahalia’s voice, any more than it was just Martin’s courage and determination, that gave the movement its strength. The power came from the community that responded so deeply to the songs that, as King wrote, ‘bind us together . . . help us march together.’ The songs Mahalia sang were both a call for renewal and a response to her people’s courage” (11). Mahalia Jackson often performed when Dr. King spoke, and has been credited for shaping his famous “I have a dream” speech at the 1963 March on Washington, calling to him to ‘tell ‘em about the dream, Martin’ and prompting him to leave his notes behind to create perhaps the most famous riff in a speech in modern memory. “The music of the early sixties wasn’t immune to the tensions that helped produce it. But in a world defined by both unprecedented economic opportunity and historic struggle for human dignity, music helped the beloved community find meaning in the past and possibility in the future. Some people held to music as a way of resisting what they saw as destructive changes, refusing to surrender the values of the gospel impulse. Others set out to imagine new possibilities for the coming world, arguing that black music had always showed you how to make a way out of no way. It was the difference between Martin and Mahalia on the one hand, Malcolm and John Coltrane on the other. The early sixties belonged to gospel; the late sixties would belong to jazz” (Werner, 2006, 100). Pop and Crossover – “A Change is Gonna Come” (Sam Cooke) Although gospel music stirred church congregations and propelled them into the streets to march for change, the Civil Rights movement was equally fueled by student activists rising up on their high school and college campuses and demanding equal rights and fair treatment under the law. While these students could appreciate the gospel music of their parents and grandparents, they wanted a new sound to embody their new experiences on the vanguard of their social justice work. Pop and crossover music, with its faster beats, brighter sound, and catchy lyrics provided the musical outlet for young people to embrace, and through which could envision the world they were working to create. Ward (1998) writes As Martin Luther King had warned the racists and massive resisters in his account of the Montgomery bus boycott, confidently entitled Stride toward freedom, “We will soon wear you down by our capacity to suffer. And in winning our freedom we will so appeal to your heart and conscience that we will win you in the process.” Black enthusiasm for black pop and its white counterpart was in many ways the cultural expression of a similar faith in the eventual triumph of the freedom struggle and the possibilities of an integrated, equalitarian America (127). As students in the civil rights movement looked to pop music to give them a unique musical voice in the struggle, some gospel artists, including Sam Cooke and Mavis Staples and the Staples Singers, saw crossover music as a way to build bridges between the stalwart gospel texts they had grown up with, and the pop tracks embraced by the younger generation. While there were detractors who suggested that musical crossovers were tantamount to renouncing their religious faith, most crossover musicians experienced success moving into new musical markets, and many crossover songs made their way onto the growing set list for the growing civil rights soundtrack. Indeed, Werner (2006) observes that Sam Cooke’s song, “A Change is Gonna Come” “expresses the soul of the freedom movement as clearly and powerfully as King’s ‘Letter from a Birmingham Jail’” (33). Songs of Protest – “Which Side Are You On?” (SNCC Freedom Singers) Gospel, pop, and crossover blends between the two each provided songs to motivate, encourage, and inspire Civil Rights activists, but the Movement was a force unto itself, and it required music of its own. Cordell Reagon and the Freedom Singers, originally a college singing group at Albany State College in Georgia, became a regular fixture at SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) events, as their fusion of gospel rhythms and protest chants in congregational, call and response style singing generated momentum in training and recruiting students to join the Movement. The Freedom Singers, and other musicians who embraced this protest genre of music, were flexible, riffing off other genres and established songs and changing the lyrics to suit the protest of the moment. Ward (1998) writes that “Civil rights activists cheerfully plundered R&B and soul, along with gospel, hymns, spirituals, union songs, folk, country and any other music they could lay their larynxes on, to create new material fitted for a particular incident, moment or theme in the Movement” (203). Similarly, they would choose the style and rhythm that suited their audience, moving between more R&B styles with younger crowds, and gospel favorites with older audiences. Such flexibility and adaptability were crucial to a Movement that relied on a base of college activists on one hand, and middle-aged and older working men and women on the other. Addressing this customization, Ward (1998) observes: “When they were not mining r&b for lyrical inspiration, young activists sometimes customized existing freedom songs by grafting r&b-style arrangements onto them, rather than using the more usual gospel-spiritual-folk musical settings” (203). As the Civil Rights Movement gained momentum, White allies joined in working for the cause, both at the grassroots level in marches, sit ins and freedom rides, and in musical performance, with artists like Pete Seeger and Bob Dylan recording anthems to support social change, justice, and racial equality. The pop music of the 1950s had already broadened the interracial listening audience of both Black and White music, and protest singers capitalized on, and extended, that musical integration. Rock ‘n Roll – “The Times They Are A-Changin’” (Bob Dylan) As the Civil Rights Movement grew in power and influence, a new kid on the musical block emerged with gyrating hips and a driving guitar beat, fusing influences from pop, the blues, jazz, R&B, and never-before-heard beats and rhythms. Rock and roll arrived with fanfare and, predictably, controversy, and, although not everyone liked it, it had its own contributions to make to the push for racial justice and equality in the United States. Watching Elvis Presley shake his hips on national television, and observing the frenzied screaming of young people – especially young women – caught in the thrall of Beatlemania, parents and pastors alike were concerned about the influence of rock and roll on their children. Even Martin Luther King Jr. issued stern warnings, saying, “The profound sacred and spiritual meaning of the great music of the church must never be mixed with the transitory quality of rock and roll music” (in Ward, 1998, 173). Whatever Dr. King (and many others) thought of it, however, rock and roll was here to stay, and in its own way, to help. Famed record producer Ralph Bass recalls: . . . they’d put a rope across the middle of the floor. The blacks on one side, whites on the other, digging how the blacks were dancing and copying them. Then, hell, the rope would come down, and they’d all be dancing together. And you know it was a revolution. Music did it. We did it as much with our music as the civil rights acts and all of the marches, for breaking the race thing down” (in Ward, 1998, 130). Musicians and their music had been crossing racial lines with increasing frequency and success since the jazz boom of the 1920s and 30s, but in rock and roll, in the heart of the Civil Rights Movement, musical miscegenation reached a zenith as young people – Black and White together – shared their love of all things rock and roll in dance halls and clubs across the country. Although not all rock and roll musicians were involved with, or supportive of, the Civil Rights Movement, many found ways, both overt and covert, to use their positions to lend a hand. Artists like Chuck Berry (in “The Promised Land”) and Paul McCartney (in “Blackbird”) made veiled references to the civil rights struggles of freedom riders in the South and students working to integrate public schools in Little Rock, Arkansas. Pete Seeger, Peter, Paul and Mary, and Bob Dylan all recorded songs that celebrated peace, justice and equality. The Beatles proved themselves staunch, if unwitting, allies by developing collaborative relationships with Black musicians and songwriters, and by refusing to play for segregated audiences, or in venues with racially-based seating arrangements. While rock and roll would not necessarily be featured on the Civil Rights Movement soundtrack, it nonetheless played a vital role in advancing the goals of the Movement itself. As the 1960s came to a close, the mood in country changed yet again, moving from the poppy optimism of the 1950s, through the anthemic protests of the 1960s, the dawn of the 1970s was darker, more disenfranchised. The great leaders of the Civil Rights Movement, and of the nation, were gone. The murders of John F. Kennedy and his brother Robert, of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr., and the deaths of tens of thousands in the seemingly endless Vietnam War had dampened the nation’s energy and enthusiasm for change. And yet, change was still necessary. Racial equality had not been realized, and with the sense that the Movement was, for all intents and purposes, over without realizing its ultimate goals, created a sense of dissatisfaction and disengagement in many. Soul – “What’s Goin’ On?” (Marvin Gaye) While soul music certainly offered its own rhythmic gestures and sonic interpretations as a unique musical genre, much of the message of the soul music that emerged following the Civil Rights Movement grounds its lyrical stance in messages of Black identity and Black pride. Musicians seemed to be saying, ‘If this is as far as America is willing to move in recognizing our equal status and inherent worth, we’ll proclaim the rest ourselves.’ James Brown’s “Say it loud, I’m Black and I’m proud” and Curtis Mayfield and The Impressions’ “We’re a Winner” ushered in a new kind of lyricism, one that celebrated Blackness rather than focusing on assimilation or racial homogeneity. Soul music wasn’t all about Black pride, however. Ward (1998) writes that “Perhaps the broader significance here is that soul, like all major black cultural forms, ultimately embodied the diversity, ambiguities, and paradoxes of the black experience in America, as well as its common features, certainties, and essences” (183). Still, the memory of music’s power and influence in the Civil Rights Movement was still fresh in the national consciousness, and new groups of activists, including the Black Panther Party, began considering its usefulness to their work. Unfortunately, however, this sometimes resulting in the over-politicizing, and thereby under-musicalizing, of the songs. . . . the Panthers tended to underestimate the politics of pleasure. They neglected the sensual gratification which crucially shapes an audience’s potential receptivity to any message in popular music and makes it difficult for any artist to ‘educate,’ let alone ‘mobilize,’ without first entertaining (Ward, 1998, 414). It was perhaps this failure to balance the politics with the pleasure that resulted in the decline of popular protest music throughout the 1970s. Hip Hop swaggered into the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s, brash and unapologetic, determined to be seen and heard on its own terms. A combination of syncopated rhymes and driving, rhythmic beats, hip hop artists were a force of nature, compelling multiracial audiences who became entranced not just with their music, but with their perceived lifestyle. Much like rock and roll in the 1950s and 60s, parents and pastors revolted against this new influence in the lives of their children, even convening congressional hearings on the inappropriateness of hip hop’s lyrics and accompanying art (and graffiti), but, again as in the 1950s and 60s, their revulsion fell on deaf ears, and hip hop became increasingly entrenched in American musical culture. Black Lives Matter – “Freedom, freedom, Where are you?” (Beyonce feat. Kendrick Lamar) The #BlackLivesMatter (BLM) movement grew out of the rising epidemic of police violence against young Black men, specifically after the murder of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin in Florida in 2012. Their stated goal is to “(re)build the Black liberation movement” (www.blacklivesmatter.com/about). As a new movement in a new century, Black Lives Matter is generating a new soundtrack of protest music that speaks to the issues of today, which, while rooted in those of yesteryear, are unique in this moment in time, both for their complexity and their prevalence, and the ways in which those things can be shared in this information age with internet technology and social media platforms. The Black Lives Matter movement is intersectional, working to end victimization, dehumanization, and oppression for not just young Black men, but women, queer, transgender, and disabled people, and all the Black voices so often silenced and forced into positions of powerlessness by government at any level. For this reason, although hip hop provides rich soil for growing the music of this movement, there is a complicated relationship between the two. Morgan, a contemporary hip hop feminist, writes: We need a voice like our music – one that samples and layers many voices, injects its sensibilities into the old and flips it into something new, provocative, and powerful. And one whose occasional hypocrisy, contradictions, and trifeness guarantee us at least a few trips to the terror-dome, forcing us to finally confront what we’d all rather hide from” (1999, 62). She is speaking to both artists and consumers of hip hop, asking that all voices and realities be represented in the music, and that when there is an issue that creates controversy, that the artists and consumers be ready and willing to confront that head on, and to learn and grow from it. She believes that the importance and impact of hip hop cannot be overestimated, observing that Hip-hop will always be remembered as that bittersweet moment when young black men captured the ears of America and defined themselves on their own terms. Regenerating themselves as seemingly invincible bass gods, gangsta griots, and rhythm warriors, they turned a defiant middle finger to a history that racistly ignored or misrepresented them. (Morgan, 1999, 101-102). Nonetheless, Morgan and others believe that there must be a sea change in society, and in hip hop, in order to disrupt the cycles of violence that hip hop often seems to glorify or perpetuate. The soundtrack of Black Lives Matter, then, must also disrupt the trope of glory by violence. Morgan notes Since hip-hop is the mirror in which so many brothers see themselves, it’s significant that one of the music’s most prevalent mythologies is that black boys rarely grow into men. Instead, they remain perpetually post-adolescent or die. For all the machismo and testosterone in the music, it’s frighteningly clear that many brothers see themselves as powerless when it comes to facing the evils of the larger society, accepting responsibility for their lives, or the lives of their children (1999, 74). This is the mythology that Black Lives Matter seeks to interrogate and rewrite to empower Black men, and the Black community, to return agency to groups that have been marginalized, disenfranchised, and left behind or, more tragically still, left to die. With countless media images circulating of Black bodies left lying in the street or in cars after police shootings – Michael Brown, Philando Castile, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, and on and on, ad nauseum – it is crucial that both the BLM movement and its music offer a counter-narrative to that of the “big bad Black man put down before he can hurt anyone.” Enter the 21st century musicians who are aligning themselves and their music with Black Lives Matter: Beyonce, Kendrick Lamar, D’Angelo, Janelle Monae, and Common, to name a few. Perhaps the first, most public entry came from Queen Bey, whose halftime performance of “Formation,” with its fashion nod to the Black Panther Party and its Black is beautiful lyrics (“I like my baby heir with baby hair and afros/I like my negro nose with Jackson Five nostrils”) set the stage for serious conversation – and criticism – by foregoing a more homogenized pop performance and instead embracing a Black pride centered musical narrative and performance. A week later, Kendrick Lamar took the Grammy stage in a chain gang uniform with his medley of “The Blacker the Berry” (“This plot is bigger than me, it’s generational hatred/It’s genocism, it’s grimy, little justification”) and “Alright” (“Wouldn’t you know/We been hurt, been down before/Nigga, when our pride was low/Lookin’ at the world like, “Where do we go?”/Nigga, and we hate po-po/Wanna kill us dead in the street fo sho’”), explicitly calling out society in general, and law enforcement in particular, for the systematic oppression and destruction of Black lives. While it can be credibly argued that two performances did not, and perhaps could not, turn the tide in favor of the BLM movement, it can be just as credibly asserted that these two, very public performances by very popular performers opened a door to more and deeper conversation about the state of race relations in the United States in the 21st century. As #BlackLivesMatter continues to grow and to develop its own soundtrack for protest and social change, hip hop will likely be at its core. While this may alienate some older listeners, and even some venerable veterans of the last Civil Rights Movement, it is important to remember, in Morgan’s words, that . . . hip-hop can help us win. Let’s start by recognizing that its illuminating, informative narration and its incredible ability to articulate our collective pain [as] an invaluable tool” (1999, 80). Note: The songs listed in each subtitle can be combined to create a playlist for students to access in order to deepen their understanding of the music for each time period, and the musical influences that shaped both the music of the Civil Rights Movement and the #BlackLivesMatter movement.Race Music: A Brief History

Music and the Civil Rights Movement

Black Power Takes the Stage

The Rise of Hip Hop

Objectives This unit is intended for high school students. Although it is being written for 10th grade students, it could easily be adapted for use in grades 9-12. Students in my school take English in a 90-minute daily block for one semester. This block schedule allows for great flexibility in planning activities, but it is important to bear in mind that all content must presented in a 4.5-month window. Objectives for this unit include:

A variety of strategies will be utilized throughout the unit in order to guide students into deep thinking and analysis of song lyrics and historical documents. Differentiation strategies are also embedded in each activity to ensure that students at multiple ability levels can engage with the content meaningfully and successfully. Each day’s lesson follows a similar structure, beginning with a “Do Now” activity as students come into class to help them settle into the class and focus on the lesson ahead. The lesson is then divided into three segments: direct instruction (provided by the teacher), guided practice (teacher and students working together), and independent practice (students working alone or in small groups, but with limited teacher assistance). The class ends with an exit ticket to serve as a formative assessment of each student’s learning for the day. Within this structure, the following strategies will be implemented: Annotating Text – This strategy allows students to really dig into a text, highlighting key words and phrases, and making notes about connections or questions they uncover as they read. Daily Journal – Often the daily ‘do now’ activity, the daily journal prompt is projected on the SmartBoard at the front of the classroom and invites students to engage with a 5-7 minute writing prompt to stimulate their thinking around the topic(s) being covered in the day’s lesson. It also serves as an attention getter, often designed around a controversial topic or question. Guided Listening – Because music is the central feature of this unit, students will be asked to listen to a variety of songs in a variety of genres. In order to prompt them to deeper analysis in this listening, it will be important to provide them with guidance for each listening exercise. Songs will be listened to at least twice, and often more than that. The first listen will be to hear the overall text and timbre of the song. The second (and potentially subsequent) listen will be to look for examples of something specific (i.e. How does the song use volume [crescendo and diminuendo] to influence the listener? Which words/phrases does the singer emphasize?). Jigsaw Reading – The jigsaw strategy is a useful method to help a whole class of students access a number of texts without reading all of them as a whole class. When using this strategy, the teacher provides different readings to small groups of students (for example, a class of thirty students might be broken into six groups of five students each, and each group would receive a different text to work with). Each group is responsible for reading and discussing their selection, and then presenting what they learned from their reading to the class. Disseminating the information from the reading can occur in several ways, including: Quick Write – A quick write is much like a daily journal, except that it takes place during the events of the lesson (as opposed to at the beginning of class) and it asks students to respond to a specific moment or idea under discussion in the lesson at that time. Quick writes can be used to help students clarify their own thinking (in which case they are not turned in for grading), to spur discussion (in which case students are asked to share what they wrote aloud), or as a form of formative assessment (in which case they are collected for teacher review). Venn Diagram – Venn Diagrams (and other, similar, graphic organizers) are useful tools for helping students identify similarities and differences between two texts. For this unit, they can be used to help students compare and contrast songs from the same era, songs of different eras, issues from different eras, etceteras. Vote With Your Feet – In this strategy, students use their bodies to create a human continuum of positions on an issue. For example, if students are asked, “Do you believe students should have to wear a school uniform?” students would move to one side of the classroom to vote ‘no’ and to the opposite side of the room to vote ‘yes.’ They also have the option to take a position somewhere in the middle, but they must be able give a reason for the position they chose.

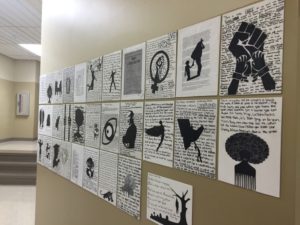

This unit is built around music, and so sampling and analysis of songs should form the backbone of the unit, with supplemental expository texts provided to help students contextualize and better understand the lyrics of each selected piece. Potential song lists for both the Civil Rights Movement and the Black Lives Matter movement are provided in the Resources section of this document. A sample lesson for guided analysis of a song is provided in this section, as well as a lesson integrating expository text, and a suggested summative project for the unit. This lesson will serve as an introductory lesson in the unit, and will provide students with the protocol for close reading of song lyrics and guided listening of a song. The goal of this lesson is to introduce students to both the topic and the foundational skills necessary for success in this unit. The lesson begins with a journal prompt: Read the following lines from “Ella’s Song.” What do you think they mean? Why? When do you think this song was written? What makes you think so? “We who believe in freedom cannot rest/We who believe in freedom cannot rest until it comes” (From “Ella’s Song” by Sweet Honey in the Rock) Explain to students that this song was written by Sweet Honey in the Rock, an African American women’s a cappella group founded by former SNCC Freedom Singer, Bernice Johnson Reagon. Ask students if they know/remember from history class who Ella Baker was? If not, either provide them with information or ask a student to look it up and report out to the class. Be sure that students understand that Ella Baker was a lifelong, grassroots activist who participated in Civil Rights Movement and continued her social justice work until her death in 1986. Introduce students to the idea of guided listening. Explain that you will play the song for them to listen to at least twice. The first time, they should just listen and jot down notes of any words, phrases, or musical moments that stand out to them. Play the song (and/or video of the Sweet Honey in the Rock performance). Ask students for feedback – what did they like/dislike? What did they hear/notice? What stood out to them? Explain to students that they’ll be listening to the song a second time, but this time they are to listen for some specific elements. They should take notes as they listen and be prepared to discuss what they heard. You can select any elements that you’d like them to listen for, but some suggestions include: After the song ends, share your notes with the students (either read aloud or projected for them to look at) and ask for them to contribute to create a whole class response to the guided questions. NOTE: The first round through, limit the questions to 2-3 so students can really focus. As they get more practice with the protocol, the questions can be increased, or introduced in subsequent rounds of listening. Provide students with a copy of the song lyrics (either printed or projected). Ask them to perform a close reading and annotation, making notes about the meaning of each line of the song. At the end of the close reading, they should use their notes and annotation to write a one to two paragraph summary explaining what they song means, why they think it was written, and what message it’s designed to convey in performance. They should use evidence from both the written lyrics and the vocal performance to support their response. Invite students to share their paragraphs aloud with the class. NOTE: Consider completing this activity with your students, at the least the first time, and then share your response with them to provide them with a model. Students’ completed paragraph(s) serve as an exit ticket for this lesson. This lesson focuses on how art and music are used, reinterpreted, and sampled to reimagine new forms of expression. The goal of this activity is to build a bridge from the legacy of the Civil Rights Movement into contemporary relevance for students. The lesson begins with a journal prompt: Are all historical moments ‘fair game’ for artists in creating new works? (If students are stuck, offer them an example, i.e. Would it be okay for a comedian to use the 9/11 attacks as material for jokes in a New York City comedy club?) Ask for volunteers to share their thoughts/ideas with the class and encourage class discussion, eliciting support for multiple points of view. Next, ask students what they remember from their earlier study of Emmett Till. Solicit examples of why the Till case was a watershed moment for the Civil Rights movement. Project lyrics of the Lil Wayne feature in Future’s song, “Karate Chop.” [Lyrics: “Pop a lot of pain bills/Bout to put rims on my skateboard wheels/Beat that pussy up like Emmett Till”] Ask students whether or not Lil Wayne had a right to evoke the cultural memory and legacy of Emmett Till in this way; facilitate class discussion, encouraging multiple viewpoints. Ask students to stand and vote with their feet, standing on one side of the room to vote “yes, he has the right as an artist to utilize any cultural memories in service of his art” or on the other side to vote “no, he does not have the right to coopt a cultural memory for profit and/or in a disrespectful way.” Students may also stand between the two points, creating a human continuum of stances on the issue, but must be able to articulate a rationale for their position. As students take their seats, share with them the letter written by Till’s family regarding Lil Wayne’s lyrics, and Lil Wayne’s response. Ask students to judge whether or not Lil Wayne’s reaction to the family was sufficient, and to explain their reasoning. Project the Dana Schutz painting, “Open Casket” (2016), depicting an artistic rendering of the iconic photo of Emmett Till in his casket. Explain that the display of this painting at the Whitney Museum’s biennial show in 2017 generated significant controversy. Ask students to complete an independent quick write assessing what they believe caused the controversy, and whether or not Schulz had the right to use this cultural moment in a work of contemporary art. Divide students into groups; give each group a different article about the Schutz painting and exhibit. Ask students to read the article together and determine (a) the belief espoused in the article about the appropriateness of Schutz’s work and (b) whether or not they agree or disagree with the author of the article. Ask each group to report out to the whole class, giving a summary of their article, a restatement of their author’s belief, and a report on which group members agree/disagree with the author and why. After all groups have reported out, encourage continued class discussion. At the end of the discussion, project Mamie Till’s words – “Let them [the public] see what I’ve seen” – about choosing to share the image of her son in the casket. Ask students what they believe Mamie Till would have to say about Schutz’s painting and why they believe that. Assign students the following writing prompt, to be completed in the final moments of class and collected as they leave for the day: Why do contemporary artists turn to moments of cultural history and memory to incorporate in their music/art/etc.? What rights and responsibilities do they have when they do this? Borrowing artistic style from the works of Kara Walker and Tim Rollins/KOS, students will create an artistic composition to represent aspects of their identity and a social justice issue of great importance to them. Taking the album as a graphic symbol, students will create a 2-frame piece, inscribing a written composition about their own personal identity on one album, and a written composition about a social justice issue of importance to them on the other side (a la an A and B side of an album). Students may choose to repurpose song lyrics for either their A side or B side composition, but the other side must be an original written piece. Students will then compose an “artist statement” explaining and interpreting their choices. Students will present their artwork to the class, with an abbreviated version of their artist statement. Artwork will be exhibited in the hallway as a gallery show. This activity will require at least a week of class time. A suggested schedule follows: Day One: Introduce students to the art of Kara Walker and Tim Rollins and KOS. Ask students to observe, specifically, how the artists use silhouette and text to create images, and how the combination of text and image can create new meaning in their works. Allow students to spend some time independently investigating examples of the artists’ work (a Google image search is a useful tool for this). At the end of day one, ask students to complete an exit ticket identifying a favorite image they found by either artists and an explanation of their choice. Day Two: Introduce the summative project to students. Explain that they will be required to make personal identity (Who am I?) statement and a social justice (What matters to me) statement. Explain that one statement must be an original composition, but that the other may include a repurposing of song lyrics (and/or other texts studied in class) to make their statement. Give students the remainder of the period to begin working on their written statements. Days Three, Four, and Five: Students will need extensive time to create their art, including time to sketch out the pieces, to create them with paint and/or markers, and to shellac them for posterity (including requisite drying time). While they wait for their pieces to dry, students can work on the Artist’s Statement that will be displayed with their work in the hallway gallery. Optional Extension: After students’ art projects have been completed and dried, designate an “Artist’s Expo” day in class to allow each student to present their finished work and to read their Artist’s Statement to the class. Students will create side by side albums, and then create the text on top of the album image. Sample image of a similar project, created with art boards, Sharpie markers, and Mod Podge shellac.Introductory Activity: Music and Protest

Do Now:

Direct Instruction:

Guided Practice:

Independent Practice:

Exit Ticket:

Mid-Unit Activity: Building a Bridge from Civil Rights to #BlackLivesMatter

Do Now:

Direct Instruction:

Guided Practice:

Independent Practice:

Exit Ticket:

Culminating Activity: Artistic Expression – Identity and Protest

Black, S. (2014). “’Street Music,’ urban ethnography, and ghettoized communities.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(2), 700-705. Blum, A. (2016). “Rhythm nation.” Studies in Gender and Sexuality, 17(3), 141-149. Cooper, B.C., Morris, S.M., and Boylorn, R.M., Eds. (2017). The crunk feminist collection. New York: Feminist Press. Brooks, D.A. (2016). “How #BlackLivesMatter started a musical revolution.” The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/mar/13/black-lives-matter-beyonce-kendrick-lamar-protest Darden, R. (2016). Nothing but love in God’s water: Black sacred music from sit-ins to Resurrection City, volume 2. University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press. Dennis, A.L. (2016). “Black contemporary social movements, resource mobilization, and black musical activism.” Law and Contemporary Problems, 79(29), 29-51. Ellison, M. (1989). Lyrical protest: Black music’s struggle against discrimination. New York: Praeger Press. Freeland, G.K. (2009). “’We’re a winner’: Popular music and the black power movement.” Social Movement Studies, 8(3), 261-288. Gosa, T.L. and Nielson, E., Eds. (2015). The hip hop and Obama reader. New York: Oxford University Press. Jones, L. (1963). Blues people: Negro music in white America.” New York, NY: William Morrow and Company. Kernodle, T.L. (2008). “I wish I knew how it would feel to be free”: Nina Simone and the redefining of the freedom song of the 1960s. Journal of the Society for American Music, 2(3), 295-317. Kot, G. (2014). I’ll take you there: Mavis Staples, the Staple Singers, and the music that shaped the civil rights era. New York: Scribner. Love, N.S. (2002). “’Singing for our lives’: Women’s music and democratic politics.” Hypatia, 17(4), 71-94. Monson, I. (2007). Freedom sounds: Civil rights call out to jazz and Africa. New York: Oxford University Press. Morgan, J. (1999). When chickenheads come home to roost: My life as a hip hop feminist. New York: Simon and Schuster. Rabaka, R. (2013). The hop hop movement: From R&B and the civil rights movement to rap and the hip hop generation. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. Radano, R. (2003). Lying up a nation: Race and black music. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. Ramsey, G.P. (2003). Race music: Black cultures from bebop to hip-hop. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. Saul, S. (2003). Freedom is, freedom ain’t: Jazz and the making of the sixties. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Sell, M. (2008). “Don’t forget the triple front! Some historical and representational dimensions of the black arts movement in academia.” African American Review, 42(3-4), 623-641. Tate, G. (1992). Flyboy in the buttermilk: Essays on contemporary America – an eye-opening look at race, politics, literature, and music. New York: Simon and Schuster. Taylor, K.Y. (2016). From #blacklivesmatter to black liberation. Chicago: Haymarket Books. Thomas, L. (2008). Don’t deny my name: Words and music in the black intellectual tradition. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press. Verity, M. (2017) “How jazz musicians spoke out for racial equality” Retrieved from: https://www.thoughtco.com/jazz-and-the-civil-rights-movement-2039542 Ward, B. (1998). Just my soul responding: Rhythm and blues, black consciousness, and race relations. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. Werner, C. (2006). A change is gonna come: Music, race, and the soul of America. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press. Mid-Unit Activity; Article: “Lil Wayne apologizes for ‘inappropriate’ Emmett Till lyric” http://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/lil-wayne-apologizes-for-inappropriate-emmett-till-lyric-20130501 Article: “Emmett Till family calls for a meeting with Lil Wayne” https://www.usatoday.com/story/life/people/2013/05/03/emmett-till-family-lil-wayne-lyrics/2131633/ Article: “White artist’s painting at Whitney Biennial draws protests” https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/21/arts/design/painting-of-emmett-till-at-whitney-biennial-draws-protests.html Article: “Why Dana Schutz painted Emmett Till” http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/04/10/why-dana-schutz-painted-emmett-till Article: “The painting that has reopened wounds of American racism” https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/apr/02/emmett-till-painting-reopened-america-wounds-race-exploitation-dana-schutz Article: “Creator of Emmett Till ‘Open Casket’ at Whitney Responds to Backlash” http://www.nbcnews.com/news/nbcblk/creator-emmett-till-open-casket-whitney-responds-backlash-n736696 Culminating Activity Kara Walker’s art: https://www.artsy.net/artist/kara-walker/works Tim Rollins and K.O.S. art: https://www.artsy.net/artist/tim-rollins-and-kos Playlist of songs inspired by the Civil Rights Movement: http://www.npr.org/2013/07/09/199105070/the-mix-songs-inspired-by-the-civil-rights-movement Playlist of songs inspired by Black Lives Matter: http://www.rollingstone.com/music/pictures/songs-of-black-lives-matter-22-new-protest-anthems-20160713 Black Lives Matter Movement: http://www.blacklivesmatter.com Lyrics to and performance video of “Ella’s Song”: http://ellabakercenter.org/blog/2013/12/ellas-song-we-who-believe-in-freedom-cannot-rest-until-it-comesReferences:

Resources for Students:

Resources for Teachers

Content Standards: Pennsylvania Content Standards for English Language Arts, grades 6-12 (available at: http://static.pdesas.org/content/documents/PA%20Core%20Standards%20ELA%206-12%20March%202014.pdf)