Author: Keysiah Middleton

School/Organization:

Eugene Washington Rhodes Middle School

Year: 2013

Seminar: From Slavery to Civil Rights

Grade Level: 6-8

Keywords: Abraham Lincoln, African American History, capitalism, Civil War, emancipation, History, Middle School, primary source documents

School Subject(s): African American History, American History, History, Social Studies

Abraham Lincoln’s pivotal role in emancipating four million African Americans is examined using primary source analysis. A careful analysis of the documents tells the story of emancipation coming to fruition. Lincoln emancipated African Americans under great duress and conflict, some reluctance and without any intent for it to initially benefit the African American. The documents also reveal Lincoln’s drastic transformation in his position towards slavery over the course of his presidency. And what became clear “is that Lincoln hated slavery not only because of its brutality and inhumanity, but first and foremost because it constituted the theft of another person’s labor-both of the slave and that of the white men who had, in effect, to compete disadvantageously in the market place with slave labor.”(Gates, Lincoln on Race & Slavery, page xxx) However, Lincoln was adamant about maintaining the Union at whatever the cost. This unit will explore how Lincoln came to free the slaves, evaluate the various transformations he experienced to provide a deeper understanding of the changes he endured to make emancipation a reality and to provide a connection to the Civil War using stories of emancipation that give witness to the role African Americans played in securing their own freedom. Upon completion of the lessons and activities in this unit, students will be able to formulate their own conclusions as well as construct their own inferences of the American Civil War and African American Emancipation based on this in depth study of primary source images and documents related to the Civil War and emancipation.

Download Unit: 13.01.01-unit.pdf

Did you try this unit in your classroom? Give us your feedback here.

It all started when Abraham Lincoln won the presidential election of 1860. Initially, he ran as a Republican candidate on a platform that argued against the institution of slavery expanding westward as the United States acquired more territory. The irony of this victory is that “Lincoln himself said virtually nothing about race or colonization in 1859, although on one occasion he did reiterate his opposition to black suffrage.”[1] The fact that he won the presidential election speaks volumes of the political and social atmosphere in America during that time because “Lincoln was not even on the ballot in the South.”[2] American Southerners were outraged because they saw the beginning of the end of a way of life that they had become not only accustomed to, but also very wealthy from. “Slaves, even more than land, were the Southern planters’ most valuable and reliable capital asset: not only did they produce annual income (and increase in number over time); they also could be mortgaged, rented, or liquidated quite easily, at prices that were rising steadily each year.”[3] Southerners began threatening to secede from the Union. At the time, states were being added to the Union by Congressional approval. As the country’s new leader, Lincoln sought to maintain the Union. Some scholars believe that Lincoln used the institution of slavery as a means to accomplish an end. “What is clear is that Lincoln hated slavery not only because of its brutality and inhumanity, but first and foremost because it constituted the theft of another person’s labor- both the labor of the slave and that of the white men who had, in effect, to compete disadvantageously in the marketplace with slave labor.” [4] As a result of this Southern outrage, Lincoln altered his political tone in an attempt to assuage southerners when “he reaffirmed that he had no intention of interfering with slavery in the southern states, and added that he had no power to do so under the Constitution. He pledged to enforce the fugitive slave law, and he endorsed the proposed constitutional amendment protecting slavery in the states that had just passed Congress.”[5] White Southerners were not moved by this change in Lincoln’s political position and “the cotton states began calling for secession as soon as the outcome of the November balloting became clear. South Carolina was the first to go announcing its departure from the union on December 20. Within six weeks Florida, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas went the same way. In February 1861 delegates from the seceded states met in Montgomery, Alabama, drew up a Constitution for the Confederate States of America, declared themselves an independent nation, and demanded that the United States surrender all the military fortifications within the South’s boundaries.”[6] Lincoln never acknowledged the Confederate States of America. He believed that these states had no legitimate grounds to sever ties with the Union and create their own country. Lincoln felt that “secession was not merely unjustified, he declared; it was unconstitutional.” [7] He seemed to have focused his energies on his crusade against slavery by strategically planning his attacks on slavery from various angles. Lincoln and his administration began drafting and implementing policies that would negatively affect the institution of slavery. Consequently, the entire idea of secession backfired on the southern states because the slavery legislation that once protected them did not apply to the Confederate States of America. “The government’s assault on slavery commenced almost immediately. Little more than a month after Fort Sumter, Lincoln’s secretary of war, Simon Cameron, signed off on a policy declaring runaway slaves contraband of war. After several amendments and revisions both houses of Congress passed the first Confiscation Act in early August 1861. Lincoln ordered the federal government to begin the aggressive suppression of the illegal Atlantic slave trade. In December, Lincoln ordered McClellan to stop Union troops from turning away slaves who had escaped to Washington, DC and to arrest any masters who tried to recapture fugitives in the nation’s capital.”[8] This new position was a reversal of what the Republican Party had their candidate run on. The government’s immediate response to the attack on Fort Sumter is what fueled this southern outrage. It became apparent to white southerners that Lincoln had been strategic in his plan that would set them and their way of life up for ultimate failure. In a desperate attempt they resorted to secession as an inevitable way to salvage whatever they possibly could of their southern way of life. [1] Foner, Eric, 2010, The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery, New York, W.W. Norton & Company, pages 133-134 [2] Hahn, Steven, 2013, “From Slavery to Civil Rights” Teachers Institute of Philadelphia Seminar, University of Pennsylvania, January 29, 2013 class lecture [3] Goodheart, Adam, 2011, 1861: The Civil War Awakening, New York, Alfred A. Knopf, page 66 [4] Gates Jr., Henry Louis, 2009, Lincoln on Race & Slavery, Princeton, Princeton University Press, page xxx [5] Gienapp, William E., 2002, Abraham Lincoln and Civil War America: A Biography, Oxford, Oxford University Press, page 78 [6] Oakes, James, 2007, The Radical and the Republican: Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, and the Triumph of Antislavery Politics, New York, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. pages 133-134 [7] Ibid, page 140 [8] Ibid, pages 143 and 147

The goal of this unit is to serve as a supplemental primary source document analysis component to the history curriculum to give our students the missing intricate details that will help with content comprehension while focusing on the required academic standards to build skills. The central purpose of this unit is to provide students with hands-on Civil War and emancipation-related primary source documents to increase their content knowledge of the topic and subtopics as well as enhance critical thinking skills. This will be achieved by engaging students in intense examination of various primary sources, completing graphic organizers and implementing various academic skills such as distinguishing fact from opinion, determining author’s purpose, verifying point of view, making an inference and drawing conclusions as well as comparing and contrasting. This supplemental unit can be implemented in a middle school general education learning environment. Lessons may be modified and chunked based on the student’s academic needs. Differentiated instruction is required to meet the assortment of our students’ many learning styles. This documentary analysis can complement an American History and African American History curriculum. For purposes of reading and content examination, this unit can also function as an extension to an English course. With the American History program of study, this component can be aligned with portions of the textbook that touch upon the causes of the Civil War. The documents can be exploited to enlighten group discussion and collaborative group projects about the countless positions regarding the causes of the war. Students can refer to the various scholarly arguments that say Lincoln’s principal goal was to maintain a solidified Union or those that say he used the institution of slavery and the slave to save the Union as their basis for a debate. The goal here is to give students a mixture of positions so that they can make a validly sound argument. Bestselling author, Chiamanda Ngozi Adichie warns us of “The Danger of the Single Story” in her TED Talk. When armed with a multitude of information regarding the diverse perspectives, our students can view the subject matter in its entirety and defend their own positions. This type of dialoguing, using the Socratic Circle discussion technique, will reveal the many insights of our students as it relates to the topic allowing the lesson to be student-centered. Student-centered lessons give students the opportunity to learn from one another. This is useful because classroom textbooks do not delve into the complicated details of Lincoln’s strong stance against slavery, why he held such a strong view against slavery, how he was politically deliberate in using slavery to win an election, then ultimately putting an end to slavery and maintaining the Union. When teaching American History, this element becomes compatible with the curriculum since numerous parts to the African American story are omitted from history textbooks. For instance, the story of Baker, Mallory and Townsend of Fort Monroe, Virginia is not written in history textbooks. However, their story when taught in conjunction with The First and Second Confiscation Acts of 1861 and 1862 can be powerful when revealing how instrumental African Americans were in securing their own freedom during the war. “Three slaves spied a chance to liberate themselves. The three slaves decided to choose their own allegiance. And they joined the Union.”[1] This, too, is yet another story on the list of textbook omissions. This also provides students with a real connection to history. This will segue into a Socratic Circle of whether or not slaves played a vital role in acquiring their emancipation. Usage of this Civil War event will aid in building subject matter comprehension. Also included in this lesson will be the label now attacked to runaway slaves and Lincoln’s political shrewdness in defying the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 to create new legislation to bring those slaves onto the Union side. “The theory behind the new law was that runaway slaves could be confiscated or held as contraband only if they had been used in the Confederate war effort. This made it difficult to enforce the Fugitive Slave Law in any consistent way. The ‘incidents of war’ as Lincoln liked to call them, were rapidly turning the Fugitive Slave Act into a dead letter.”[2] The fugitive slave laws can be contrasted with the two Confiscation Acts as a collaborative group project providing our students with the experience of determining how one law nullifies another. The American Civil War and African American Emancipation: A Documentary Analysis provides a great opportunity for teachers of different disciplines to collaborate with one another to implement the same theme to drill content matter for students to master the subject matter and accompanying skills. The readings from this unit can be taught in an English course so that students can conduct document analysis as it relates to text. Document analysis will deepen the student’s critical thinking and writing skills as well as an enhanced understanding of Abraham Lincoln’s speeches, debates, legislation and other written correspondence. Reading, writing and discussing similar subject matter in various classes aides our students not only in this mastery of knowledge and skills process, but in successfully retaining this newly acquired knowledge. [1] Goodheart, Adam, 2011, 1861: The Civil War Awakening, New York, Alfred A. Knopf, page 298 [2] Oakes, James, 2007, The Radical and the Republican: Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, and the Triumph of Antislavery Politics, New York, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. pages 133-134.

The strategies for this unit will coincide with the Pennsylvania Common Core State Standards for Literacy in History/Social Studies. These strategies will include the use of text and image document analysis, academic skills, graphic organizers, collaborative group activities, written exercises, technology, assessments and a culminating exercise. Eugene Washington Rhodes Middle School as a School District of Philadelphia school uses The Seven (7) Step Lesson Plan format) with Homework as an extension of the lesson). This format is used to provide a more structured type of daily instruction to achieve greater academic student success. This teaching format essentially involves an “I Do, We Do, You Do” interactive approach that gradually engages students in the lesson using the following components: These components are posted daily as the class agenda giving students a visual of what is expected from them during the course of the class period. The “Objective” describes the intent of the lesson from the onset. Our students should know immediately what it is that they are studying, why they need to know this particular information, how this information will be applicable to them in real life and how they will accomplish acquiring said lesson in order to get a handle on the subject matter quickly. The “Do Now” is a brief warm up exercise related to the previous lesson for review or as an assessment strategy or as a precursor to the current lesson to build background information and to segue into the current lesson. “Direct Instruction” is strictly teacher-centered. The details of the lesson are introduced here. This is the “I Do” portion of this teaching format. Students typically take lesson notes during the direct instruction segment. “Guided Practice” calls for the lesson to be modeled. The teacher must exhibit what is to be accomplished during this part of the lesson. Repeated instruction or drilling the content occurs during this part of the lesson. The lesson must be modeled repeatedly using Bloom’s Taxonomy to address the assorted learning levels and styles of our students. This can be difficult because it involves differentiating the instruction to meet all the needs of our students. Subsequently, considerable thought must be put into Guided Practice when planning your lesson. The guided practice piece of the lesson is the “We Do.” “Independent Practice” stipulates that students put into practice the lesson they have learned during the direct instruction. It is imperative that our students work independent of any assistance so that they may be successful during the assessment of the lesson. Also, it is important that students work free of teacher involvement so that she can adequately gage the student’s level of comprehension of the lesson. This is where it is determined if students have achieved mastery of the topic and can move on or if the lesson will need to be re-taught. Consequently, this “I Do” part of the lesson must be strictly adhered to. “Closure” is simply restating all that was ascertained from Direct Instruction, Guided Practice and Independent Practice. This and the “Exit Ticket” allows the teacher to do a quick assessment of her student’s knowledge base of the lesson taught or activity completed. Finally, “Homework” serves as an extension of the current lesson to give our students additional practice to master the topic. Homework must frequently be assigned and assessed to determine comprehension levels and if students need additional instruction. The lesson plan format coupled with an array of teaching strategies such as the Before, During and After (BDA), TAG writing strategy and PLORES will not only build content comprehension, but also our student’s reading, writing and sight word vocabulary skills. BDA is a comprehension assessment strategy that involves a series of teacher made questions to identify a student’s level of understanding. TAG is a writing technique that involves turning the question (writing prompt) into a statement, answering the question and giving supporting details as a guide to writing more effectively. PLORES is an acronym for the combined reading, writing and process of elimination technique that requires students to predict what they believe the reading assignment is about, locate supporting details during the reading, organize these details to answer questions or writing prompts regarding the reading, re-read anything that it not understood and evaluate/eliminate any answers that are chosen or disregarded. These teaching strategies must be implemented in the beginning of school and drilled on a consistent basis during the school year so that using them will become habitual techniques to our students.

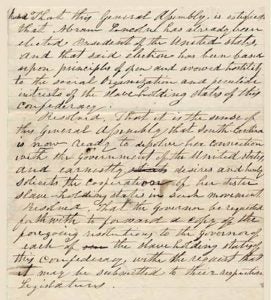

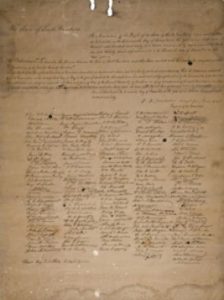

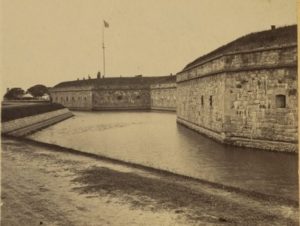

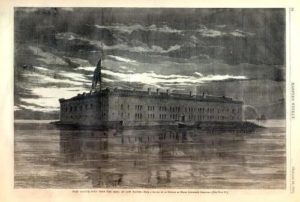

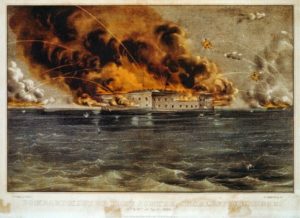

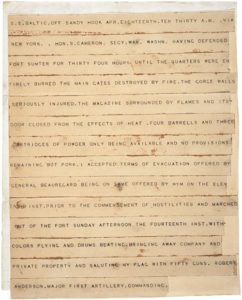

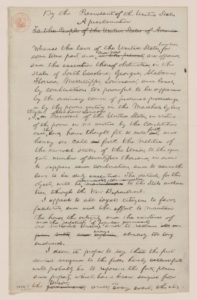

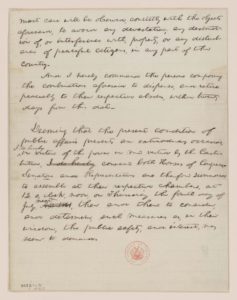

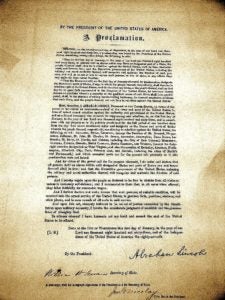

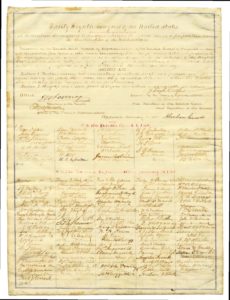

“The South Publicly Goes Against President Lincoln” Lesson objective: SWBAT explain why southern Democrats were outraged at the election of Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 Presidential Election using a primary source document, document analysis and a graphic organizer. Distribute the document and read it as a group. Use the Before, During, After (BDA) as a guided reading strategy to assess content comprehension. Distribute document analysis worksheet (See Appendix) to guide students in analyzing the document. Encourage extended dialogue during inquiry. Have students give as many details as possible. (See Appendix) Have students use the same primary source document with a graphic organizer to answer questions regarding fact and opinion. Have students complete a brief writing prompt using the key terms detailing in fifty (50) words or less why the Southern states were outraged about Lincoln winning the presidential election. “South Carolina Secedes From the Union” Lesson Objective: SWBAT explain how South Carolina seceded from the Union using a primary source document, document analysis and a graphic organizer. Distribute the document and document analysis worksheet (See Appendix). Read the document aloud as a group. Ask questions frequently to assess the student’s understanding. Guide students along in the document analysis process encouraging them to provide as many details as possible. “The Attack on Fort Sumter” Lesson Objective: SWBAT explain the attack on Fort Sumter and President Lincoln’s response using primary source Civil War images as well as documents, image analysis, document analysis and graphic organizers. Fort Monroe during the Civil War, Library of Congress Fort Sumter in Charleston SC harbor before it was bombarded in the Civil War Painting of Fort Sumter burning in Charleston, SC harbor on April 12, 1861 Fort Monroe today, with the city of Hampton, VA beyond it. The star-shaped citadel is the Civil War-era fortress Courtesy of the City of Hampton Telegram Announcing the Surrender of Fort Sumter (1861) Lesson Objective: SWBAT explain how the surrendering of Fort Sumter sparked the Civil War and Lincoln to act swiftly using Civil War documents and descriptive writing. “Lincoln’s Proclamation on State Militia” (1860) Distribute the document and the document analysis worksheet (See Appendix). Students will work independently to complete the analysis. Lesson Objective: SWBAT describe how President Lincoln used his powers as Commander in Chief to call loyal states to provide troops in an effort to reclaim forts and property seized by the Confederates using a primary source document analysis worksheet. Lesson 6: “Lincoln Suspends the Writ of Habeas Corpus” (See Appendix) Lesson Objective: SWBAT explain a Writ of Habeas Corpus is and where the right of a Habeas Corpus comes from using the United States Constitution. SWBAT describe the circumstances surrounding Lincoln’s suspension of the writ of habeas corpus in 1861 using the United States federal court case Ex parte Merryman and primary source document analysis. Distribute excerpts of the document to the collaborative groups for analysis using the document analysis worksheet (See Appendix). “Mallory, Baker and Townsend: Virginia Slaves Who Became Contraband” (1861) Lesson Objective: SWBAT make a real life connection to the Civil War by describing how African Americans played a pivotal role in obtaining their freedom using a Civil War story. SWBAT describe how the escape, capture and contraband label of Virginia slaves Mallory, Baker and Townsend from their Confederate slaveholders to Fort Monroe at the start of the Civil War led to military legislation using a graphic organizer, primary source drawing and secondary source. Gen. Benjamin Butler’s decision to seize runaways as contraband is a milestone often overshadowed in Civil War history by tales of generals and battlefield strategy. (Photo: Library of Congress) Brigadier General F. Benjamin Butler Library of Congress Illustration — African-American fugitives entering the fort in the summer of 1861 “The First Confiscation Act of 1861” Lesson Objective: SWBAT explain circumstances surrounding the creation of The First Confiscation Act of 1861 using background knowledge and primary source document analysis. “The Second Confiscation Act of 1862” Lesson Objective: SWBAT explain how The Second Confiscation Act of 1862 went beyond The First Confiscation Act of 1861 to include treason and a label for slaves using the skill of compare and contrast. “The Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation” and “The Final Emancipation Proclamation” Lesson Objective: SWBAT describe and discuss the basis of the “Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation” and the use of “The Final Emancipation Proclamation” as a military war measure to weaken the Confederacy. “The Thirteenth Amendment” (1865) Lesson Objective: SWBAT explain the process in the making of “The Thirteenth Amendment” SWBAT engage in debate after viewing the 2012 film “Lincoln” written by Doris Kearns Goodwin, directed by Steven Spielberg and starring Daniel Day-Lewis using a film analysis worksheet and the BDA strategy.Lesson 1:

Agenda:

Lesson 2:

Agenda:

Lesson 3:

Agenda:

Lesson 4:

Agenda:

Lesson 5:

Agenda:

Agenda:

Lesson 7:

Agenda:

Lesson 8:

Agenda:

Lesson 9:

Agenda:

Lesson 10:

Agenda:

Lesson 11:

Agenda:

Suggested Teacher Readings Belz, Herman, 1998, Abraham Lincoln, Constitutionalism, and Equal Rights in the Civil War Era, New York, Fordham University This book analyzes the nature and tendency of American Constitutionalism during the nation’s greatest political crisis The Civil War. In a series of related essays, Herman Belz combines detailed narrative with probing judicial analysis of the political thought of Abraham Lincoln, his exercise of executive power, and the application of the equality principle which would become a central issue during Reconstruction. Bennett, Jr., Lerone, 1999, Forced Into Glory: Lincoln’s White Dream, Library of Congress Cataloging Beginning with the argument that the Emancipation Proclamation did not actually free African American slaves, this dissenting view of Lincoln’s greatness surveys the president’s policies, speeches, and private utterances and concludes that he had little real interest in abolition. Pointing to Lincoln’s support for the fugitive slave laws, his friendship with slave-owning senator Henry Clay, and conversations in which he entertained the idea of deporting slaves in order to create an all-white nation, the book, concludes that the president was a racist at heart—and that the tragedies of Reconstruction and the Jim Crow era were the legacy of his shallow moral vision. Blight, David W., 2001, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory, Cambridge, MA, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Blight delves deeply into the shifting meanings of death and sacrifice, Reconstruction, the romanticized South of literature, soldiers’ reminiscences of battle, the idea of the Lost Cause, and the ritual of Memorial Day. He resurrects the variety of African-American voices and memories of the war and the efforts to preserve the emancipationist legacy in the midst of a culture built on its denial. Boritt, Gabor S, 1978, Lincoln and the Economics of the American Dream, Memphis, TN, The Memphis State University Press This unique exploration of Lincoln’s economic beliefs shows how they helped shape his view of slavery, his conduct of the war, and most fundamentally his understanding of what the United States was and could become. Copeland, Matt, 2005, Socratic Circles: Fostering Critical and Creative Thinking in Middle and High School, Portland, Maine, Stenhouse Publishers This is a coaching guide for both the teacher new to Socratic seminars and the experienced teacher seeking to optimize the benefits of this powerful strategy. Socratic Circles also shows teachers who are familiar with literature circles the many ways in which these two practices complement and extend each other. Effectively implemented, Socratic seminars enhance reading comprehension, listening and speaking skills, and build better classroom community and conflict resolution skills. Foner, Eric, 2008, Our Lincoln: New Perspectives on Lincoln and His World, New York, NY, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. Several of these original essays focus on Lincoln’s leadership as president and commander in chief. James M. McPherson examines Lincoln’s deft navigation of the crosscurrents of politics and wartime strategy. Sean Wilentz assesses Lincoln’s evolving position in the context of party politics. On slavery and race, Eric Foner writes of Lincoln and the movement to colonize emancipated slaves outside the United States. James Oakes considers Lincoln’s views on race and citizenship. Foner, Eric, 2010, The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery, New York, NY, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. This landmark work gives us a definitive account of Lincoln’s lifelong engagement with the nation’s critical issue: American slavery. Gates, Jr., Henry Louis, 2009, Lincoln on Race and Slavery, Princeton Acclaimed Harvard scholar and documentary filmmaker Henry Louis Gates, Jr., presents the full range of Lincoln’s views, gathered from his private letters, speeches, official documents, and even race jokes, arranged chronologically from the late 1830s to the 1860s. Complete with definitive texts, rich historical notes, and an original introduction by Henry Louis Gates, Jr., this book charts the progress of a war within Lincoln himself. We witness his struggles with conflicting aims and ideas–a hatred of slavery and a belief in the political equality of all men, but also anti-black prejudices and a determination to preserve the Union even at the cost of preserving slavery. We also watch the evolution of his racial views, especially in reaction to the heroic fighting of black Union troops. Gienapp, William E., 2002, Abraham Lincoln and Civil War in America: A Biography, New York, Oxford University Press Gienapp begins with a finely etched portrait of Lincoln’s early life, from pioneer farm boy, to politician and lawyer in Springfield, to his stunning election as sixteenth president of the United States. We see how Lincoln grew during his years in office, how he developed a keen aptitude for military strategy and displayed enormous skill in dealing with his generals, and also how his war strategy evolved from a desire to preserve the Union to emancipation and total war. Goodheart, Adam, 2011, 1861: The Civil War Awakening, New York, Alfred Knopf As the United States marks the 150th anniversary of our defining national drama, 1861 presents a gripping and original account of how the Civil War began. Goodwin, Doris Kearns, 2005, Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln, 2004, New York, NY, Simon & Schuster Paperbacks Acclaimed historian Doris Kearns Goodwin illuminates Lincoln’s political genius in this highly original work, as the one-term congressman and prairie lawyer rises from obscurity to prevail over three gifted rivals of national reputation to become president. This brilliant multiple biography is centered on Lincoln’s mastery of men and how it shaped the most significant presidency in the nation’s history. Guelzo, Allen C., 2004, Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation: The End of Slavery in America, New York, NY, Simon & Schuster Paperbacks Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation dispels the myths and mistakes surrounding the Emancipation Proclamation and skillfully reconstructs how America’s greatest president wrote the greatest American proclamation of freedom. Levine, Bruce, 1992, Half Slave and Half Free: The Roots of Civil War, New York, NY, Hill and Wang Levine explores the far-reaching, divisive changes in American life that came with the incomplete Revolution of 1776 and the development of two distinct social systems, one based on slavery, the other on free labor–changes out of which the Civil War developed. Library of Congress, 1989, Abraham Lincoln: Speeches and Writings, 1859-1865, Speeches, Letters, and Miscellaneous Writings Presidential Messages and Proclamations of the United States, Inc. This volume consists of a complete collection of works from Lincoln’s years as a lawyer up until his death. McPherson, James, 1998, Battle Cry Freedom: the Civil War Era, Oxford, Oxford University Press This book vividly recounts the momentous episodes that preceded the Civil War–the Dred Scott decision, the Lincoln-Douglas debates, John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry–and then moves into a masterful chronicle of the war itself–the battles, the strategic maneuvering on both sides, the politics, and the personalities. Particularly notable are McPherson’s new views on such matters as the slavery expansion issue in the 1850s, the origins of the Republican Party, the causes of secession, internal dissent and anti-war opposition in the North and the South, and the reasons for the Union’s victory. Oakes, James, 2007, The Radical and the Republican: Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, and the Triumph of Antislavery Politics, New York, NY, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. James Oakes has written a masterful narrative history, bringing two iconic figures to life and shedding new light on the central issues of slavery, race, and equality in Civil War America. The frontier lawyer and the former slave, the cautious politician and the fiery reformer, the President and the most famous black man in America—their lives traced different paths that finally met in the bloody landscape of secession, Civil War, and emancipation. Olsen, Christopher J., 2006, The American Civil War: A Hands-On History, New York, NY, Hill and Wang Christopher J. Olsen’s The American Civil War is the ideal introduction to American history’s most famous, and infamous, chapter. Covering events from 1850 and the mounting political pressures to split the Union into opposing sections, through the four years of bloodshed and waning Confederate fortunes, to Lincoln’s assassination and the advent of Reconstruction, The American Civil War covers the entire sectional conflict and at every juncture emphasizes the decisions and circumstances, large and small, that determined the course of events. Urofsky, Melvin I. and Finkleman, Paul, 2002, Documents of American Constitutional and Legal History, Volume I: From the Founding Through the Age of Industrialization, 2nd Edition, New York, NY, Oxford University Press Organized chronologically, this documents reader skillfully weaves together constitutional and legal history, offering students a mix of both frequently cited and lesser-known-but equally important-historical documents and court decisions that have been instrumental in shaping the nation’s constitutional development. Vest, Kathleen, 2005, Using Primary Sources in the Classroom, Huntington Beach, CA, Shell Education Developed by social studies specialists, this resource helps teachers turn classrooms into primary source learning environments. Using Primary Sources in the Classroom offers effective, creative strategies for integrating primary source materials and providing cross-curricular ideas. This resource is aligned to the interdisciplinary themes from the Partnership for 21st Century Skills. Woolman, Albert A., 1936, Lawyer Lincoln, New York, NY, Carroll and Graf Publishers The New York Times review describes Lawyer Lincoln as a chronological account of Abraham Lincoln’s twenty-three years of practicing law at the Illinois bar. It views Lincoln’s legal career not as a mere backdrop to the story of his Civil War presidency but as experience vital to his evolution from a shrewd practitioner of frontier justice into a chief executive capable of leading his nation through the most challenging period in America’s history. Goodheart, Adam, 2011, “ How Slavery Really Ended in America” New York Times, April 1, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/03/magazine/mag-03CivilWar-t.html?pagewanted=all# Widmer, Ted, 2011, “Lincoln Declares War” New York Times article http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/04/14/lincoln-declares-war/ Goodheart, Adam, 2011, “The Future of Freedom’s Fortress” New York Times article http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/08/18/the-future-of-freedoms-fortress/ Pinsker, Matthew, 2012, “Congressional Confiscation Acts,” Emancipation Digital Classroom http://housedivided.dickinson.edu/sites/emancipation/2012/07/14/congressional-confiscation-acts/ Pinsker, Matthew, House Divided: The Civil War Research Engine at Dickinson CollegeSuggested Student Readings

The Resolution to Call the Election of Abraham Lincoln A Hostile Act (1860) http://scdah.blogspot.com/2010/11/resolution-to-call-lincolns-election.html www.teachingushistory.org/pdfs/lincdoc_000.pdf The South Carolina Ordinance of Secession (1860) http://www.teachingushistory.org/lessons/documents/Ordinance.pdf “Attack On Fort Sumter” (1860) images http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/08/18/the-future-of-freedoms-fortress/#more-102789 www.charlestonbatterytour.com/fort-sumter.htm http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/08/18/the-future-of-freedoms-fortress/#more-102789 “The Future of Freedom’s Fortress” by Adam Goodheart, New York Times article http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/08/18/the-future-of-freedoms-fortress/ “Telegram Announcing the Surrender of Fort Sumter” (1861) http://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc_large_image.php?flash=true&doc=30 “Major Robert Anderson Surrenders”(1865) image www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/cwpb.02460/ “Lincoln’s Proclamation On State Militia (1861) http://www.archives.gov/northeast/nyc/education/images/union-blockade.pdf “Lincoln Declares War” by Ted Widmer, New York Times article http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/04/14/lincoln-declares-war/ “Lincoln Suspends the Writ of Habeas Corpus” http://www.archives.gov/northeast/nyc/education/images/union-blockade.pdf “How Slavery Really Ended in America” by Adam Goodheart, New York Times article http://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/03/magazine/mag-03CivilWar-t.html?pagewanted=all# Shepard Mallory, Frank Baker and James Townsend Meet Brigadier General Benjamin F. Butler After Escape photo image http://contrabandhistoricalsociety.org/ “Brigadier General Benjamin F. Butler” (1861) photo http://www.civilwaracademy.com/images/general-butler.jpg “African-American fugitives entering the fort in the summer of 1861” illustration http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/08/18/the-future-of-freedoms-fortress/ “The First Confiscation Act of 1861” http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/first-confiscation-act/ http://www.ohiocivilwarcentral.com/entry.php?rec=997 “The Second Confiscation Act of 1862” http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/second-confiscation-act/ http://www.ohiocivilwarcentral.com/entry.php?rec=999 “The Emancipation Proclamation” (1863) http://www.phawker.com/wpcontent/uploads/2007/02/emancipationproclamation.jpg “The Thirteenth Amendment” (1865) http://constitutioncenter.org/Files/thirteenthamendmentposter.pdf http://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=true&doc=40&page=transcript http://www.archives.gov/historical-docs/doc-content/images/13th-amendment.pdf “Ex Parte Merryman” (1861) http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/ex-parte-merryman/Primary Source Document Retrieval Information

The Pennsylvania Common Core State Standards for Literacy in History/Social Studies can be found at www.corestandards.org/ELA-Literacy The Common Core Standards utilized in this unit include the following: History CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.6.8-1: Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary sources. CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.6-8.2: Determine the central ideas or information of a primary source; provide an accurate summary of the source distinct from prior knowledge or opinions. CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.6-8.3: Identify key steps in a text’s description of a process related to history/social studies. CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.6-8.4: Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including vocabulary specific to domains related to history/social studies. CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.6.8.7: Integrate visual information (e.g., graphic organizers, photographs, documentary films, etc.) with other information in print. CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.6-8.8: Distinguish among fact, opinion, and reasoned judgment in a text. CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH9-10.4: Determine the meaning of text, including vocabulary describing the economic, political and social aspects of a primary source. This is a ninth grade standard that can be modified to introduce middle school students to ESP the strategy. CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.8.2: Determine a central idea of a text and analyze its development over the course of the text, including its relationship to supporting ideas; provide an objective summary of the text. CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.8.3: Analyze how a text makes connections among and distinctions between individuals, ideas or events (e.g., through comparisons, analogies, categories). CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.8.2: Write informative/explanatory texts to examine a topic and convey ideas, concepts, and information through the selection, organization, and analysis of relevant content. CCSS.ELA-Literacy.SL.8.1: Engage effectively in a range of collaborative discussions (one-on-one, in groups, teacher-led, and student-led) with diverse partners on grade level topics, texts, issues, films, building on others’ ideas and expressing their own clearly.Reading

Writing

Speaking