Author: Jessica Ramos

School/Organization:

Henry C. Lea School

Year: 2013

Seminar: Painless Statistics for Teachers and Teaching

Grade Level: 6-8

Keywords: Book logs, English, graphing, Increased reading ability, Literature, Middle, Probability / Statistics

School Subject(s): English, Literature, Math, Statistics, Writing

This unit seeks to: 1. Increase students’ awareness of their independent reading abilities; 2. Enable students to chart and track their progress; 3. Increase students’ ability to employ basic statistical processes of collecting and analyzing, presenting, and interpreting date; and 4. Use those statistical skills across curriculums.

This unit is intended for use with middle school, preferably in an English and Language Arts, ELA, setting. Cross-curricular integration, with a concept such as statistics, allows students to reduce anxiety levels by addressing it initially through a more familiar venue. Specifically, data analysis, which can seem overwhelming to students who already struggle with basic mathematical concepts.

Students will also get a chance to track their reading ability over time. They will be able to graph their starting point, their interim points, as well as their final reading level. The hope is that students will see a positive relationship between increased independent reading and independent reading ability.

Download Unit: Ramos-Jessica-unit.pdf

Did you try this unit in your classroom? Give us your feedback here.

Over the last seven years I have noticed the independent reading levels of the middle school students I teach decrease rapidly. According to the National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL), people’s reading ability has declined, despite increasing costs of schooling and increasing percentages of people making it all the way through high school generation, vs. generations ago. A survey conducted in 2003 by NAAL measured literacy along three dimensions: prose literacy, document literacy, and quantitative literacy. This survey revealed that approximately 50% of United States adults were categorized as having the lowest two of five levels of literacy. The silver lining was that people are not spending much time at all reading anymore, especially young people. Susan Williams of Show and Tell for Parents (Williams, 2008) went on to assert that the reason for the declining abilities is that when people don’t read for pleasure, they can’t read for information because their brains haven’t been developed by the mental processes that go on when you read a lot. Williams blames this problem on parents spending less quality time with young children, too much exposure to TV and video games, an explosion of other leisure-time activities that steal time away from solitary reading, and schools that seek to teach reading with the wrong instructional philosophy and methods. Due to the advent of electronic technology, children are becoming less and less likely to read on their own for leisure. For the purposes of this unit, leisure reading is defined as reading that is part of a non-work, non-school recreational activity (Kbulst and Kraaykamp, 1998). Greaney (1980) defined leisure reading as requiring a certain level of reading proficiency. This level of proficiency is not synonymous with the level at which most of my students can read independently. Children are more interested in television, video games, and smart phones, than in reading. Thomas Coffin’s Television’s effects on leisure-time activities, asserts that television-owning homes are 24% less likely to participate in non-technology related activities than non-television owning homes (American Psychological Association, 2013); activities like reading. A connection has been found between children’s leisure reading habits and their academic achievement, causing even more concern (Hughes-Hassell & Rodge, 2007; McKool, 2007; Nippold et al., 2005). As students’ academic achievement levels are falling so too is the time they spend reading for leisure. In contrast with past generations what kids consider reading in this digital age is much different than in decades past. In September of 2010, Scholastic and Harrison Group published their “Kids and Family Reading Report.” This report found that from age 6 – 17, the time kids spend reading books for fun declines while the time kids spend going online for fun and using a cell phone to text or talk increases. Parents express concern that the use of electronic and digital devices negatively affects the time kids spend reading books (41%), doing physical activities (40%), and engaging with family (33%) (Good, 2010). As well 25% of kids (age 9-17) think texting with friends counts as reading. Similarly 28% of kids (ages 9-17) think that looking through postings or comments on social networking sites like Facebook counts as reading. Therefore when the issue is raised that kids are reading by or with technology I urge those who think that to take a closer look at what’s being read and what definition of reading is implied. I do not think that reading text messages sent by friends is going to yield increased achievement on student aptitude assessments or overall reading abilities. As the common core curriculum shifts toward a focus on non-fiction text, students’ ability to read critically is increasing. Declining reading levels are the opposite of what is needed to tackle this new curriculum that is filled with complex texts and more difficult content. Increased text complexity is calling for increased levels of comprehension and vocabulary. Students are reading less and less for leisure and are therefore creating less and less background knowledge—both abilities needed for comprehension. Scores on reading inventories such as the Gates-McGinty are getting lower and lower. Students just aren’t reading enough. There is extensive research to support the premise that the best way to become a better reader is to read more (Allington, 2001).

While researching for this unit I came across a wealth of research on reading and reading ability that establishes a clear positive relationship between reading more and increased reading ability. I wish to further explore if there is a positive relationship between reading more challenging texts and reading ability. To that effect I am hypothesizing that reading more challenging texts independently will increase students’ ability to tackle text complexity in the new common core curriculum. In addition to increased independent reading I think implicit instruction in the five main comprehension strategies is, if not necessary, extremely helpful in improving reading ability. To this end, all four of my ELA sections began a reading log in January in which they read a minimum of ten pages per night in a self-selected novel (from a range of books suited for their independent reading level). One class received additional implicit instruction in the use of the five main comprehension strategies. The inability of the public education system to prepare students for higher education is astounding, assuming these kids are in fact being prepared for college. For some, this seems an unrealistic goal. Some studies show that there is as much as a 350L (lexile) gap between the difficulty of end-of-high school and college texts. This gap is equivalent to 1.5 standard deviations and more than the standard lexile difference between fourth and eighth grade on the National Assessment of Educational Progress. To put this in perspective, students who have a gap of only 250L decreased their comprehension of a text from above 75% to 50%. This means that many of my middle school students are reading grade level text, but comprehend at a rate of only about 50%.

This Unit is intended for use with middle school. The middle school schedule allots 71 minutes daily to English and Language Arts instruction, ELA. During the ELA block students are expected to receive instruction in reading, writing, speaking, and listening. This instruction, ideally, should be on grade level and involve mostly guided instruction with little time allotted for independent reading. The objectives this unit will set out to accomplish are as follows:

During this unit students will focus on five main comprehension strategies. The control group will receive implicit instruction in the five strategies good readers use. Meaningful reading cannot occur without a purpose. Even though proficient readers may not always consciously state their reasons for reading particular selections, they always have a purpose. Deciding on a purpose for reading influences, which other strategies readers will use during reading. When students do not have a purpose for reading, their reading tends to be haphazard and unfocused. Setting a purpose for reading is paramount. If you have not been provided a purpose for reading, figuring out what you are expected to recall as a result of your reading becomes a matter of guesswork (Brozo & Simpson, 2007). Teach students to set a purpose for reading by using questions such as; what is the material about? What type of material is this? Why am I reading this material? Questions such as these will help get students thinking about the authors intended purpose for the text. You can also teach students how to determine the topic of a selection before they begin to read. Explain to the students that quickly previewing/surveying a reading selection will give them some information about the topic and that knowing this makes reading much easier. Monitoring comprehension is a strategy that allows students to know when they understand and when they do not. This strategy gives them ways to “fix” problems in their understanding as the problems arise. As students read they stop frequently to ask themselves what just happened Utilizing this skill prevents students from reading an entire page or an entire text and not knowing what the text was about. Research shows that instruction, even in the early grades, can help students become better at monitoring their comprehension. Ways to Teach Monitoring Comprehension while Reading Teach students to be aware of what they do understand and identify what they do not understand. (Clewell, 2003) offers the following as a way to teach monitoring comprehension. Get a paragraph or a piece of text that’s not too long and put dots at different points in the paragraph. As students come to those dots they then tell exactly what’s going on in their head, what they’re thinking. They may be making predictions, asking questions, even thinking about something that’s confusing or something that needs some clarification. Clewell notes that many students are successful with the dots throughout the passages as they act as the cognitive cop on their shoulders letting them know they need to stop and pay attention to what they’re thinking as they’re reading. This skill is especially important for middle school students as they tend to be the population of readers who like to just read the words but they never stop to think that what they’re thinking about is important. Questioning is a strategy that can help students access the inner conversations one has when reading and comprehending. Teaching Questioning is a helpful strategy for all readers. Teaching questioning is helpful for those readers who are struggling in that it helps them to recall information that seemed tricky to them or confused them in some way. It helps “on-level” readers to pace themselves and can serve as a checkpoint throughout paragraphs or chapters to aid comprehension. Questioning is also a good skill for advanced readers as it allows them to develop deeper meaning and push themselves further into the text. The questioning strategy can be taught by reading aloud to students and sharing what you’re thinking or questioning in your mind while you read. You can describe your inner conversation to them. This is one of the best methods I to use to make reading concrete. When sharing your thinking be sure to include the outcomes you’re wondering about, the characters, new information, and concepts or themes that are emerging. Questioning is what makes you want to keep reading. If you already know what is going to happen you will be less likely to keep reading. Stephanie Harvey, (Stenhouse, 2000) a literacy consultant and staff developer for the Denver-based Public Education and Business Coalition lists four research-based steps she uses to teach the questioning strategy to her students: This strategy is helpful for any student who is struggling with a word in a text. It does, however, lend itself more to those students who are struggling with a few words as opposed to struggling with the entire text. The strategy is simply a reminder to skip the word and come back to it once you gain more insight or information that would make sense. Students use what they read to identify the unfamiliar word. This is another form of using context clues. This strategy is simple to teach and should become routine for all readers. Select a text that is unfamiliar to the group of students whom you will be working. Model the strategy by reading a sentence out loud and skipping a word. After the sentence is complete model out loud the thought process of deciding what the word might mean based on the rest of the sentence. Do this several times and then allow time for the students to practice the strategy as well. Drawing conclusions and making inferences is by far the toughest skill for struggling readers. It is often times difficult, if not impossible, for them to do. In drawing conclusions (making inferences), you are really getting at the ultimate meaning of things – what is important, why it is important, how one event influences another, how one happening leads to another. Simply getting the facts in reading is not enough you must think about what those facts mean to you. This strategy is best taught when students are reminded that they already make inferences in their daily lives. Share an example of them hearing screeching tires and hearing a loud crash, but not seeing it. Ask what they think could have caused both noises in such a quick succession. They will most likely say a car crash, which is the answer you want. Explain that they know this happened by inferring, or deciding what the two sounds-facts, meant to them. Drawing conclusions is very similar to inferring in terms of teaching the strategy. When showing students how to draw conclusions remind them that drawing conclusions refers to information that is implied or inferred. This means that the information is never clearly stated. Show students how to read between the lines by having them read a short text that is very vague. After reading have them draw conclusions that focus on or center around what, why, when, who, and how. These strategies will be taught implicitly to one section of eighth grade students. All of the sections will receive a pocket size strategy card that briefly outlines each of the five strategies and their uses. These strategies will be used while reading independently each night. The hope is that an increased use of these strategies in combination with daily reading will improve students’ abilities to comprehend difficult texts. Students will monitor their progress throughout this unit. It is the constant monitoring that will, if my hypothesis is correct, be a motivator for the students to do better. Actually seeing their progress will give them a sense of accomplishment and a reason to try harder.Set purpose for reading

Ways to Teach Setting a Purpose for Reading

Monitor comprehension while reading

Questioning

Ways to Teach Questioning

Skip, read on, and go back

Teaching the Skip, Read on, and Go Back Strategy

Draw conclusions and Make Inferences

Teaching Drawing Conclusions and Making Inferences

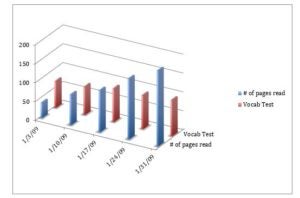

To begin this unit we need all students to establish a baseline independent reading level as determined by their score on the Gates-McGinty Reading Inventory. This assessment consists of a 45-question vocabulary section and a 48-question comprehension section. This should be completed in two separate class sessions so as not to overwhelm the students with questions. Once all students have taken the assessment and it has been scored a spreadsheet for recording the result should be created. Below is a row form such a spreadsheet. Once all students have their baseline data they will make a double bar graph that will show their baseline vocabulary and comprehension score and leave room for their next set of scores. See Appendix 1.1. They will use a subsequent monitoring chart to track progress towards their goal. This chart will be introduced in the lesson entitled Showing Me: A look at student data and different ways to display them. Prior to distributing the book logs (see appendix 1.2). Students will review “Why Can’t I Skip My 20 Minutes of Reading Tonight?” (See appendix 1.3). This document illustrates for students the vast range of words vocabulary knowledge associated with minutes read. Student A reads for 20 minutes each day for a total of 3600 minutes in a school year. Student B reads for 5 minutes a day for a total of 900 minutes in a school year. Student C reads for 1 minute each day for a total of 180 minutes in a school year. Immediately after showing this graphic in print or on an overhead or Smart board students will have time to do a think-pair-share with a partner about which student they expect to be more successful in life and why. After students discuss the question with a partner, the teacher will select a few students to share their insights with the entire class. At the completion of the discussion the teacher will distribute the book logs, which will be handed out each week. Every night the student will read and record the amount of pages read and the time spent reading; the minimum requirement will be ten pages or twenty minutes. Students will get their book logs signed either nightly or by Friday. This unit is intended to span approximately one marking/grading period, which is usually about two and a half months in length. During this period students will graph the number of pages they’ve read and the amount of time they’ve spent reading each week. They will also graph the scores to their weekly vocabulary assessments. This will be done weekly. Students may get un-invested if they are not continually returning to the data to observe progress. Due to the demands of the common core curriculum, students will complete the independent reading at home for one of their homework assignments. The initial graphs (appendix 1.1) should be kept in a centralized location so they are not misplaced or lost by students. Ideally this chart should be stapled to the inside of the manila folder that will house all the students’ data. This folder should be revisited weekly to chart pages read and vocabulary test scores. Book Logs (appendix 1.2) should also be stored in this folder Lesson Rationale: If students are able to see, actually picture, their progress towards a goal they may be more inclined or motivated to accomplish said goal. Lesson Objective: By the end of this lesson students will know how, and be able to, represent their growth in terms of reading ability on a weekly basis. After collecting four weeks of data students will be able to graph and present their data using one of the many graphic representation tools available in Microsoft Word Charts and Tables. To begin the lesson the teacher will ask students to revisit their initial Baseline graph (appendix 1.1). This graph should be stapled into a folder, preferably manila, that will house all of each student’s data. The teacher will have students review their initial vocabulary and comprehension levels. The students will reflect, in writing, whether they are pleased with their initial levels. If they are not pleased the will state how they plan to improve. If they are pleased, they too will state how they plan to move up even higher. These questions will serve as a class brainstorming session on how to improve reading levels. The class will also have a discussion about some factors that may have influenced the low scores. Students will create a simple table on a sheet of notebook paper that will be updated weekly. The table will show the number of pages read each night, if none enter zero. The table will also record the weekly vocabulary assessment score. An example of this simple table is shown below. Keeping a chart with data sets will give students the data they need to create a graphic representation of their progress towards their goal. After four weeks of data sets are collected students will construct a chart. The teacher will demonstrate how to easily create a chart using Microsoft Word. The teacher will demonstrate on the smart board how to make a chart. If there is no smart board the teachers can either walk through the steps, verbally, one-by-one with the class or pre-print the steps and distribute them or have students copy them down. Students will open a new Microsoft Word document. They will click on View, Elements Gallery, then Charts. Once in Charts students will see eleven categories of charts to choose from. For the purposes of this lesson and to be sure everyone can practice doing the same thing the students will select a 3-D Column Chart. Selecting a chart will navigate students to an excel sheet that is already set up and just needs values for the X-axis, Y-axis and the data sets. Students will enter their data from the first four weeks of recoding them. Assuming the student read more pages each week and did better on each subsequent vocabulary assessment they would have a chart that looks something like the example below. The hope would be that seeing their own data represented would be more of a motivator to keep reading and to improve. The example shown above is just one of the many graphs students can make using Microsoft word. Students will have the option of making any graph that makes sense to them. To close the lesson the teacher will inform students that they will be making a graphic representation each month up until and including May, when they take their final Gates-McGinty reading inventory assessment. Each time they will need to select a different visual representation. Lesson Rationale: This lesson on comprehension strategies will be taught to one eighth grade section. The thought is that this group will improve more than the control groups because they’ll have the aid of implicit instruction on the strategies. If students can utilize even one of the five major comprehension strategies while reading they will gain more from the text at hand. Lesson Objective: By the end of the class period students will be able to define the five major comprehension strategies and show evidence of using each strategy to better understand a text, shown by completing a graphic organizer (appendix 1.5) with at least five entries. To begin, the teacher will pose the following question “Who ever found themselves reading something and asking themselves what did I just read?” This question will serve as a discussion starter on what comprehension is and how to get better at it. Once students have talked for a few minutes, no more than 4, about what they currently do when they’re stuck in a text or what they do if they don’t understand something the teacher will provide students with brief notes to copy down on the five main comprehension strategies. The teacher will go over each skill and give an example. Students will then get into small groups and practice using each strategy. This practice can be done with any text the students are currently reading. Students will complete a graphic organizer that asks which strategy was used, why it was used, and how it helped. They will complete one entry for each strategy. To close the lesson students will be counted off by 5s and placed in similarly numbered groups. Each group will come up with a quick 3-5 minute presentation of when and how to use one of the strategies. (The teacher will decide which group gets which strategies.) Lesson Rationale: As an end to this unit, preferably in may, after all students have recorded their final progress on the Gates-McGinty assessment, they will have a chance to display their data as a whole. Each class will create a visual representation of the entire classroom’s data. The students will be able to choose from the following visual representations and data sets. If the class wants to display their data differently or focus on different data they can, as long as they can justify why. These visual representations can be presented to other classes or even better to the whole school. If presenting to the entire school is not feasible the representations can be displayed in a centralized location such as a hallway.Part I – Baseline Assessment (Data Collection)

Last Name

First Name

Reading Level

Baseline (January)

May

Vocabulary (V)

Comprehension (C)

Total (T)

V

C

T

Doe

Jane

7.7

9.4

8.4

Part II – Graphing/Representing Data

Part III – Book Logs

Part IV – Charting progress

Lesson One: Showing Me: A look at Student Data and Different Ways to Display Them

Week 1

# of pages read

Weekly Vocab. Test Score

February 25-28

45

85

March 4-7

60

88

Lesson 2: Utilizing Comprehension Strategies to Increase Reading Ability

Lesson 3: Culminating Activity

Borzo, W. & Simpson, M. Content Literacy for Today’s Adolescents. University of Georgia: Pearson Education Inc, 2007. This book describes setting a purpose for reading in great detail. It gives teachers practical ways in which they can implement this strategy in their classrooms. Clewell, S. “Reading Strategies” retrieved from www.thinkport.org/career/strategies/reading/monitor.tp. on March 29, 2013. This website provides a great overview on monitoring comprehension. It provides teachers specific take away strategies that can be used to teach students to monitor their comprehension. Greaney, V. (1980) “Factors related to the amount and type of leisure reading.” Reading Research Quarterly, 15:3, 337-357. This article provides an overview of the different factors that influence students’ time and/or want to read for leisure. Knulst, W. & Kraaykamp, G. (1998) “Trends in leisure reading: forty years of research on reading in the Netherlands.” Poetics, 26:1 (September), 21-41 This article explores the trends in leisure reading with the advent of technology. It highlights the shifts in technology and explores why these shifts may have affected peoples inclination to read for leisure. Williams, S. (2008) “Why Reading Skills Are Declining.” Retrieved from www.showandtellforparents.com. on April 11, 2013. http://www.tweentribune.com This website provides articles for all age groups, many from the Associated Press. It is an excellent resource to promote leisure time reading, electronically Students will need access to varied novels and novellas as well as non-fiction books on topics they are generally interested in. They will also need the required graphs, charts and worksheets, available in the appendix. Pocket sized strategy cards will also be need and can be created by shirking the strategy card included in the appendix. Students will need writing utensils and coloring instruments to construct some of the graphs and charts. They will need manila, or any type, folders to house all of their data. They will also need notebooks for note taking on the comprehension strategies. Computers with Microsoft Word software will be needed to make the charts and tables. However, students can create hand drawn graphs if computers aren’t available.Teacher Resources

Student Resources

Classroom Materials

Student Name: ______________________________________________ Baseline Reading/Final Reading

Appendix B Name: ________________________________ Week of Monday February 25, 2013 – Thursday February 28, 2013 Monday 2/25 Tuesday 2/26 Wednesday 2/27 Thursday 2/28 Note- This book log will be distributed in the weekly homework packet and collected each Friday. However, it can be given independent of a homework packet. Depending on time it could also be filled out during class.

Date

Pages Read

Parent Signature

Strategy I used to better understand it __________________________________________________ How did using this strategy help? Strategy I used to better understand it __________________________________________________ How did using this strategy help? Strategy I used to better understand it __________________________________________________ How did using this strategy help? Strategy I used to better understand it __________________________________________________ How did using this strategy help? Strategy I used to better understand it __________________________________________________ How did using this strategy help? Comprehension Strategies Graphic Organizer

Part of Text I Didn’t Understand

Part of Text I Didn’t Understand

Part of Text I Didn’t Understand

Part of Text I Didn’t Understand

Part of Text I Didn’t Understand

Set a Purpose for Reading: Why am I reading this? Why did the author write it? What do I want to get out of this text?

Questioning: What just happened? How would it be different if…? Why did the character do/say that?

Monitor Comprehension: Do I understand what I just read? Do I need to go back and re-read? Will a quick summary help me right now?

Skip, Read On, and Go Back: I don’t understand this word/phrase I’ll go back and read the sentence before this one. I don’t really understand this part I will come back to it once I get some more information.

Drawing Conclusions: Can I come to any conclusions about the plot? Characters? Content?

The common core state standards are in full swing in Pennsylvania. The following standards are part of the new core and will be addressed during this unit.