Author: Freda/Frankie Anderson

School/Organization:

The U School

Year: 2019

Seminar: Environmental Humanities from the Tidal Schuylkill River

Grade Level: 9-12

Keywords: activism, environment, Health, social studies, STEM

School Subject(s): Activism, Environmental Science, Health, Science, Social Studies

This unit is for high school students. Students test lead in school. Students synthesize findings into user friendly zines explaining the scope of the lead problem within the school, the work students have done on the project, preventative tips, and actions which can be taken against this poison. They plan and promote the town hall by canvassing the neighborhood. Students create a presentation showing how the school’s lead problem relates to the larger problem in the neighborhood. Students give a call-to-action speech declaring access to safe neighborhoods a human right. Students break into 7 stations which guests can visit.

Stations:

Media from this event and the planning process is shared on social media and maintained by students.

Download Unit: Anderson-F.-19.02.08.pdf

Did you try this unit in your classroom? Give us your feedback here.

The U School High School sits in the 19122 area code. There is a very real threat of lead in the drinking water in Philadelphia’s 19122 area code. Before the 1950s, many houses were built using lead pipes. According to the Philadelphia Health Department, between 56 and 74 percent of houses in the 19122 were built before the 1950s. The high school I work in was built in the 1920s. In September 2017, a Philadelphia public school student developed serious brain damage from eating lead paint chips which fell from the ceiling of his classroom. Later in the school year, the School District decided it was finally going to do some of the toxicity tests teachers and parents had been begging them to do for decades. The results have not been good, and the actions taken based on the toxicity results have been unacceptable. At our school, a letter was sent out by the district stating that lead levels of 8.4ppb were found in the main kitchen sink which is used to cook all of our student’s food. The letter also stated that it would be doing nothing to combat this issue, as its action level was capped at 10ppb lead concentration or higher. There is not a lot that staff and students of The U School can do about changing the lead levels which exist in the school; just as there isn’t a lot the students and residents of the neighborhood can do about changing the lead pipes in their own homes. Replacing residential lead pipes has an estimated cost of $3,000 – $8,000 while the students and surrounding neighborhood live almost entirely below the poverty line and can not afford this replacement. As defeating as this information may be, one power that The U School does have at its disposal is the ability to educate itself and others. At The U School, students must demonstrate mastery in certain competencies for each class in order to earn credit and graduate. In the Organize Lab Class (a community activism class taught by the author), some of the core competencies are “How Well Can I Plan, Promote, and Host a Successful Community Event?” “How Well Can I Motivate My Community to Take Action?” and “How Well Can I Design and Facilitate Workshops to Educate Others About Important Community Issues?” The unit created in the Teachers Institute of Philadelphia for Organize Lab will be a Community Education Lead Safety Town Hall and Workshop. The Organize Lab students will collaborate with 9th grade Physical Science students to test lead within the school. The Organize Lab students will help the Science students synthesize their findings into a user friendly zine which explains to participants at the neighborhood town hall the scope and sequence of the lead problem within the school, the work that the students have done on the project, helpful preventative tips, and direct actions which can be taken against this poison. They will plan and promote the community town hall by canvassing in the neighborhood. The U School students will put together a compelling presentation about the ways in which the school’s individual lead problem relates to the larger lead problem which affects the entire neighborhood. Organize Lab There are many ways in which the work from Environmental Humanities from the Tidal Schuylkill River and Bethany Wiggin’s teachings and resources will inform this unit. The zine which students will create and distribute is inspired by a resource provided by Bethany Wiggin entitled Ecotopian Toolkit. There is a grant attached to the Ecotopian Toolkit, that if won, could be used to expand the zine portion of the project which could make it into something participants at the town hall contribute to and be a part in creating. Drawing on concepts from the Marisol de la Cadena reading as well as past readings of Rachel Carson’s The Sense of Wonder, students will spend time at either the Schuylkill, the Delaware, Tacony Creek, etc., simply taking in the water as an entity and making observations about how the water interacts and exists unto itself, with nonhuman wildlife, and with the human population of the City of Philadelphia. This experience will help them garner a feeling of belonging when it comes to the water that surrounds this city and therefore instill a feeling of duty to keep the water safe for others and demand water safety as a basic right for themselves. The Essential Questions for this unit are: 1. What factors have allowed inhumane living conditions to be seen as “normal” for some communities, but seen as “unacceptable” for others? 2. How can we identify and fight against inhumane living conditions. I do not think it is possible to teach a unit about environmental injustice and not address the imbedded racism, classism, and sexism that comes with it. This is the reasoning for the first Day 1: What is an inhumane living condition? Day 2: In school water experience investigation. What is water at school? What is our relationship to it? Day 3: Out of school water experience. What is water in (a river, a creek, a lake, wherever we can get to)? What is our relationship to it? Day 4: What is intersectionality? Day 5: What is environmental racism? Environmental classism? Day 6: Article and podcast response to Philadelphia’s lead water risk. Day 7: Philadelphia blood lead levels map to poverty level map to racial map comparison and analysis. Day 8: Interview with science students preparation: how do I conduct a strong interview? Day 9: Write strong interview questions, receive feedback, revise and finalize questions. Day 10: Conduct interview with science students about their lead findings and research. Day 11: Share interview experience. Discuss interview process. Debrief. Day 12: Analyze and interpret information collected. Evaluate findings. Draw conclusions. Day 13: Pamphlet Information Breakdown 1, Why is lead bad? Day 14: Pamphlet Information Breakdown 2, How can you prevent poisoning? Day 15: Pamphlet Information Breakdown 3, Why does this project matter to The U School and Organize Lab and you? Day 16: Pamphlet Information Breakdown 4, Explain this project. What are the science kids doing? What are you doing? Day 17: Pamphlet Information Breakdown 5, Call to action. What do you want people to do about it? Why/how are we fighting for clean water? Day 18: Choose your group for the town hall. Day 19-21: Work with your group. Day 22: Class flyering day. Day 23-24: Water activist investigations. Day 25: Pamphlet Information Breakdown 6, Explanation of your clean water activist(s). Explain what other water activists are doing around the world to fight for this issue. Day 26: What makes an aesthetically pleasing pamphlet? Day 27: Organize all Pamphlet Information Breakdown sections into a single pamphlet. Day 28: Get feedback on pamphlet. Day 29: Finalize and turn in pamphlet. Day 30: Last minute group work. Area of Learning: Deliver a Solution: Day 31: Town hall. Carry out your group’s job at the town hall. Day 32: Reflect on town hall and overall project. Celebrate success. Analyze growth areas. There are a few main places where I can see the content from TIP coming into play. Firstly, in the beginning when we’re spending time with water, we will read some of the poetry from Flow by Beth Kephart. We will use some of the passages as inspiration as we write our experiences in the presence of water, both when we visit at school and outdoors. Secondly, a lot of the water activists can be explored in the activist investigation section of project, which will take place from Day 21-Day 23. Some of the activist groups which were shown to me in seminar and which I will include for my students are: Additionally I will add some water activist groups of my own into the mix: Problem Statement and Introductions:

students will give a short call-to-action speech declaring access to safe schools and neighborhoods as a basic human right. After this, students will break out into multiple different workshop stations which guests can cycle through at their leisure. One station will teach neighbors lead water safety tips like running the tap for longer and avoiding hot water as well as explaining how to access and utilize lead testing kits for their own homes. Another station will be explaining to guests what the true health effects of lead can mean for their families. Another station will be engaging in a discussion with guests about some the rich history of activists fighting for the right to clean and accessible water around the world. Another station will be collecting ideas from guests for further direct actions that can be taken. Another station will be engaging participants in a creative outlet for their frustrations, ideas, and concerns. (This creative outlet can be determined by students, whether they are more inclined to facilitating poetry prompts, sketches, short videos, etc.). Another station will be helping guests contribute to a video about the issue which will be shared with media outlets and distributed throughout the city. A final station will be collecting contact information of guests who wish to participate in future action around the topic. Photographs, videos, and media from this event and the process leading up to it will be shared on an Instagram page created and maintained by students about the project.Content Objectives

essential question. The second question is about giving my students a way to fight back against that imbedded racism, classism, and sexism. In my class, it is difficult to strike a balance between teaching students about the injustices which affect their everyday lives, and making sure they know that there is still hope, and they do possess some agency in the situation. To expose children to environmental racism with no other action for them to take part in is, in my opinion, cruel. These two essential questions are about sitting with the weight of the injustice for a second, mourning the hurt around the injustice, and then getting up to try and eradicate the injustice. In order for students to be able to really understand and interpret the clean water access problem in order to synthesize it and be able to teach it to others or demand action around it, a lot of background knowledge has to be done first. I will lay out here how I plan to build the acquisition of knowledge in individual lesson steps. The lessons start more broadly, dealing with the essential questions, and become more focused as the days go on.Area of Learning: Discovering the Problem:

Area of Learning: Defining the Problem:

Area of Learning: Designing a Solution:

Area of Learning: Develop a Solution:

Thirdly, if possible my students will be able to amp up the pamphlet quality with resources from the Ecotopian Toolkit organized by the Penn Program in Environmental Humanities. They have used their resources in the past to create zines documenting environmentalism projects that have gone on around and in relation to the river. If the program is interested in assisting us, we will be able to elevate our pamphlets to artistic zine status. This will make the information more accessible and user friendly. However, if we are not approved for assistance by the program, I can use the Ecotopian Toolkit zine as an example to my students so that they can see what they’re could possibly reach for in terms of their pamphlet design.

I teach a class called Organize Lab at The U School. Organize Lab is essentially a community activism course. We spend a little bit of time learning about activist struggles and triumphs throughout history and presently. We spend the bulk of our time however, actually taking actions around various social issues which impact the students’ lives and the world around them. Our class is project based, and every culminating performance task in Organize Lab is a major action oriented project. Although the content and specifics of our coursework changes unit to unit and year to year, the performance tasks which the students must demonstrate mastery in consist roughly of the same four things. These repeated four performance tasks are: In order to help students build to these larger and more overwhelming final projects, components of the projects are broken down into manageable parts, so that students can complete a bit at a time, and in the end, they can simple string all of the components together to create the final project. This process of breaking a large project into more bite sized pieces is often referred to as “chunking” in project based learning circles. For individual projects, like most of the campaign projects and the informational media projects, chunking happens by creating each assignment so that it fits like a piece in the final project. For example: in this project, as students work to create their pamphlets to distribute to guests at the town hall, they are completing individual sections of the pamphlet one at a time, in the form of assignments. In the end, the students can simply take all of the work that they did in the assignments, compile it in an attractive looking pamphlet template from Canva.com, add a few pictures, and turn it in. This prevents students from feeling overwhelmed and stressed out by the material. In addition to helping students, it gives the teacher more time to spend modeling and practicing each section with the students, and identifying problem areas for the class which can be focused on.

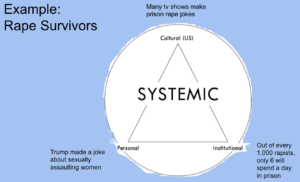

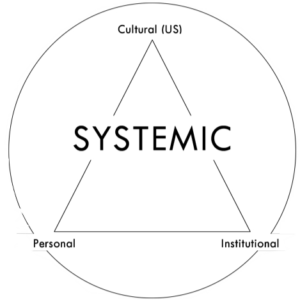

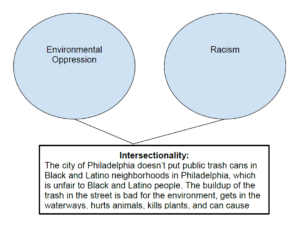

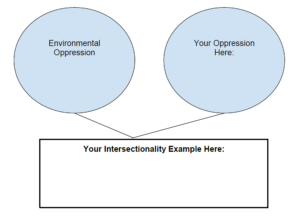

For larger performance tasks – like planning, promoting, and hosting a community event – the individual assignments are chunked as well as the roles of the various students in the creation of the final product. I playfully refer to this strategy as “chunking children.” For this project, students are chunked into different small groups, and each group plays a part in the final town hall event. The groups for this project will include: Within each group, there are chunked assignments, just like with the individual pamphlet assignments. Below is a sampling of the instructions that the individual groups get from me: Social Media Group: Here is a list of what you need to do for your social media Water Activist History Station: You will make little cards which include information on For each group, answer these 3 questions. Your answers to these questions will be printed on cards which you will pass out In this way, we can build towards creating very large scale, complicated, and public performance tasks as a class, and no one, including the teacher, becomes too overwhelmed. Notice that some of the groups require students to be physically present at the town hall (like the Kid’s Station), and other groups don’t have to literally attend the event in order to do their part (like the Press Release Group). For my student population and for the neighborhood population, this works out well. No community event would be successful if it was held during the day, as the local residents work during the day. However, many of my students have financial or familial responsibilities that they must attend to after school, making it impossible for them to stick around for an evening event. Students are asked to pick their top three job choices, and explain why they think each of their choices is a good fit for them. Then, I read through and try and match everybody in their top three. I explicitly tell students which jobs would require for them to be present at the town hall. Notice that most of the off-site jobs are more complicated, asking the students to write or create things, while some of the on-site jobs are easier and require less long-term preparation. In this way, the demands on each individual student balance out and feel pretty fair to everyone. A teacher in another context may wish to group students differently, perhaps by skillset. Some educators I have spoken to about this work have expressed concern that students will behave badly or do subpar work – which would reflect poorly on the school at such a large and public scale like a town hall. On the contrary, in my experience students work much harder and are much more attentive when they know their work actually will matter in the real world and can have a real impact on the people in their communities. The students at my school are not much motivated by grades. They are motivated however, by the idea that they might be publicly embarrassed if they don’t know what they’re talking about on stage at a town hall event. They are also motivated by the fact that, to steal an idea from Chris Lehmann, the work that they do in Organize Lab isn’t preparation for real life – the work that they do in Organize Lab IS real life. What they create matters now, and it can have a very real impact on the lives of very real people who live on the very real planet. Below are some more detailed lesson plans from the unit. Lesson for Day 2: What is an Inhumane Living Condition? What is Systemic Oppression? Materials Needed: Paper, Pencils, White Board/Chalk Board, Dry Erase Markers/Chalk Timeline for Completion: 1-2 class periods. Stated Objectives: Students will be able to identify inhumane living conditions in their communities and theorize which systems of oppression play a role in the persistence of these conditions. Standards and Competencies: PA State Standard 5.1.U.C. – Analyze the Principals and Ideals that Shape the US Government, Liberty, Freedom, Democracy, Justice, and Equality. Evaluation Tool: This is the rubric that I will use to grade this assignment. 2.3-Evaluate findings and draw conclusions Vocabulary: Oppression: Prolonged cruel or unjust treatment or control. Inhumane Living Condition: An environment that shows little to no evidence of basic compassion, kindness, health, or safety. Step 1: Have students write down what they think of when they think of the word oppression. Step 2: Have them share out what they wrote. Step 3: Have them take down the class definition for oppression. Step 4: On one side of the board, have them write down with dry erase markers every single form of oppression they can think of. Help them out by writing some obvious ones. Racism. Homophobia. Fill in words afterwards that you think are important which they may not know and didn’t write down. Ableism. Ageism. Step 5: Spend a second going over some of the oppressions that they wrote down. Clarify what a student meant where you need to. Explain any words you may have added yourself. Congratulate them on how much they already know. Build confidence here. Step 6: Have students write down what they think of when they here the term inhumane living condition. Step 7: Have them share out what they wrote. Build confidence here. Highlight where they made insightful guesses. Step 8: Have them take down the class definition for inhumane living conditions. Step 9: On the other side of the board, have them write down all the examples of inhumane living conditions that they can think of. You will need to help them with this, get some examples down first yourself. (An area with so much pollution that everyone has asthma, a school with not enough funding for an art or music class, a country where it is illegal to be gay, etc.). Step 10: Go over some of their answers, again congratulating students on their insights and building confidence. Step 11: Have students create connections with lines on the dry erase board, between the inhumane living condition and the form(s) of oppression that may be causing it. You will have to model this. (Connect asthma from pollution to racism, classism. Connect a school with not enough funding for an art and music class to ageism, racism, classism). Step 12: Intro to the Systemic Oppression Assignment. Show students the assignment. Explain the example to students. Explain that, when a form of oppression is systemic, that means its violence is replicated in multiple areas of our society. Systemic oppression is enforced in our public culture, in our personal lives, and in our country’s institutions. See assignment below, with example included. Step 13: After you have gone over the example with students, spend some time talking about the example and answering any questions they may have. Step 14: Have students choose an inhumane living condition, and fill out the systemic oppression triangle themselves in the assignment. As students are working on this, walk around and assist as needed. Step 15: Have students share their work with the class. Make a big show about clapping for them and celebrating their work. Step 16: Before students leave for the end of the day, please be sure to take some time to reassure them that, while this topic is difficult, and saddening, you are taking the time to teach it to them so that they can learn to fight back against it. Systemic oppression is very hard to destroy, it is imbedded deeply into our culture, and it’s important to acknowledge this to kids. It is validating for them to hear that the work is hard, and you as their teacher can become disheartened by it as well. It is equally important that you remind them that the goal of the unit is to bring about unity and fight against this monster. Your goal is to arm them with this information, not be cruel. Conclude. Name: Organize Lab 11th Date: 1.1 Systemic Oppression Triangle Directions: You are going to choose an Inhumane Living Condition and create a Systemic Oppression Triangle. An example is provided below. Now, think of an inhumane living condition. Create a Systemic Oppression Triangle that shows how cultures, people, and institutions work together to oppress that target group. Lesson for Day 4-5: What is Intersectionality? What is Environmental Racism? Classism? Materials Needed: Paper, Pencils, White Board/Chalk Board, Dry Erase Markers/Chalk Tape Timeline for Completion: 1-2 class periods. Stated Objectives: Students will be able to compare two forms of oppression and speculate how those systems of oppression might intersect to create an even more nuanced situation of injustice. Standards and Competencies: PA State Standard 5.1.U.C. – Analyze the Principals and Ideals that Shape the US Government, Liberty, Freedom, Democracy, Justice, and Equality. Vocabulary: Intersectionality: Overlapping systems of discrimination and oppression. Environmental Oppression: The systematic destruction of the earth, and the living/non living things which inhabit the earth. Step 1: Have students write down what they think of when they hear the word intersectionality. Step 2: Have them share out what they wrote. Step 3: Have them take out their systemic oppression triangle papers from Lesson 1. Step 4: Have students place tape on the back of their triangles, and come to the board and place their inhumane living condition paper near the oppression that they think it most closely relates to. You might have to help a student with this as an example. If a student wrote about a homeless teen, who was kicked out of his house for being gay, you might help them place that under “homophobia” on the board. Step 5: Once students have matched them, ask a few of them to share why they placed their assignments where they did. Step 6: Now is your time to challenge their thinking a bit and have them understand intersectionality more. Demonstrate for them how some of their assignments could fit with multiple forms of oppression. For example, with the gay homeless teen example, you could draw a line on the board connecting the teen example to “classism,” since the child is experiencing homeless and therefore impoverished. You can draw another line connecting the teen to “ageism,” since teens have very little agency in this country to keep themselves safe in emergency situations. Step 7: Have students come up and make lines connecting their assignments to as many forms of oppression as they can think of that affect their situation. Step 8: Have students write the class definition for intersectionality. Step 9: Have students write down what they think of when they here the term environmental oppression. Step 10: Have students share out some of their ideas. Build confidence here. Highlight good guesses. Step 11: Have student copy down definition of environmental oppression. Step 12: Unveil the assignment. Students will be showing how various forms of oppression can be intersectional with environmental oppression. Go over the example included in the assignment below with students. Step 13: Have students work independently on the second part of the assignment. They will think of a form of oppression and then they will demonstrate a situation where that form of oppression could intersect with environmental oppression. Students will need a lot of help with this. This is an extremely complicated concept. Walk around and help as needed. Step 14: Have students share their work. Build their confidence and give lots of rounds of applause. If students share something that doesn’t quite hit the mark, ask classmates to help brainstorm how to get the student there. Step 15: Conclude by tying this all back to the unit. The lack of clean water concentrated in mostly black and brown and poor areas, is an example of intersectionality with environmental oppression and racism/classism. Name: Organize Lab 10th Date: 2.4 Environmental Oppression Intersectionality Web Directions: Choose a form of oppression (from the board) and write the oppression in the blank circle. Then, explain in the web how the form of oppression you chose can intersect with Environmental Oppression. Give a specific example of this intersection. Definition of Environmental Oppression: The systematic destruction of the Earth and the living things which inhabit the Earth. Use the example below to help you. Lesson for Day 6: Article and Podcast Response to Philadelphia’s Lead Water Risk. Materials Needed: Computer or Article Printouts, Response Printouts, and Pencils. Timeline for Completion: 1-2 class periods. Stated Objectives: Students will be able to criticize local and national governmental priorities and spending in order to reimagine a more life-nurturing water supply for Philadelphians. Standards and Competencies: PA State Standard 5.1.U.C. – Analyze the Principals and Ideals that Shape the US Government, Liberty, Freedom, Democracy, Justice, and Equality. Step 1: Ask students what the purpose of the unit is. Step 2: Have them write out in a sentence or two a summary of the unit. Step 3: Have them share out. (This is all as a reminder and to help center kids for the article). Step 4: Tell kids to go to the article response assignment on Google Classroom (or pass out the paper, if using paper). Step 5: Listen to the audio podcast together, pausing at important parts to discuss. If you want, you can prompt kids to answer some of the questions in the Response sheet. Step 6: Have students read the article and respond to the questions. If you have any reading strategy procedures set up in your classroom, like reading groups or special roles, now is the time to employ them. Step 7: Have students share out their responses to the questions. If you have certain discussion strategy procedures set up in your classroom, like table discussions, podcast recordings, discussion roles, or socratic seminars, this might be a good time to scale up this assignment to a multi day assignment and employ one of those. Ordinarily, I’d only have students share out answers to the opinion based questions, like 5, 7, 8, 10, and 12. However, in this case, students are creating informational pamphlets which will be passed out to community members. Some of this information is included in the answers to these questions. So it might be a good strategy to have students share all the questions to give kids who may have missed things a chance to get them right. This is up to you, and you should judge based on the reading levels of the students your working with. Step 8: Make sure you give kids close feedback on this when you are going back in to grade it. If a student got a key piece of information wrong on this, like how many minutes to run the tap before drinking, for example, then they will end up putting the wrong information on their pamphlet and the pamphlet will be useless for the town hall event. Name: Organize Lab 10th Date: 2.3 Article Response “Philadelphia’s Building Boom Gives Rise to Another Hidden Lead Risk” Directions: Read the article and listen to the podcast (attached to the Google Classroom assignment). Answer the questions below to help you process as you are reading.

sharing preventative measures)

and sharing preventative measures)

politicians to call their attention on this issue)

hall to kick off the event)

can learn how to prevent lead poisoning in their own households)

auditorium before the event)

afterwards)

account raising awareness about lead poisoning and documenting the project and town hall)

guests can participate in a creative activity to demand the right to clean

water)

can learn about the dangers of lead poisoning)

and age appropriate activity related to clean water)

about our project and attend our town hall)

part of the project, from the very beginning, to the very end of the town hall)

door, and make sure that you have proper contact info for them)

the auditorium, and showing them where bathrooms are)

can learn about some activists across the world who have also fought/are fighting for clean water)

campaign.

The U School. 2000 N. 7th St.

we’re doing in class, or how you feel about what you’ve learned, etc.

all of the activist groups below.

at your station on May 9th.

Level 6

Level 7

Level 8

Level 10

Level 12

I can summarize my findings and explain the most important information.

I can summarize my findings and explain the information in detail.

I can summarize my findings and explain the information in detail.

I can summarize my findings and explain the information in detail.

I can summarize my findings and explain the information in detail.

I can draw logical conclusions based on my findings.

I can draw logical conclusions based on my findings.

I can draw logical conclusions based on my findings.

I can explain how my findings relate to a larger idea or concept.

I can explain how my findings relate to a larger idea or concept.

I can propose ways that my findings could be used to improve communities.

Jaramillo, C. (2017, July 17). Philadelphia’s building boom gives rise to another hidden lead risk. Retrieved from http://planphilly.com/articles/2017/07/17/philadelphia-s-building-boom-gives-rise-to-another-hidden-lead-risk This article details the city’s toxic water crisis, and explains the ways in which the problem may actually be getting worse, not better. This report includes a map which shows the lead toxicity levels found in children’s blood, as well as the likelihood that existing houses in each neighborhood contain lead pipes. This can be used to show the blatant racism and classism that exists when it comes to the disbursement of toxic lead levels in the City of Philadelphia. Laker, B., Ruderman, W., & Purcell, D. (2018, May 22). Children face potential poisoning from lead, mold, asbestos in Philadelphia schools, investigation shows. Retrieved from http://media.philly.com/storage/special_projects/lead-paint-poison-children-asbestos-mold-schools-philadelphia-toxic-city.html This article is actually about lead paint, but it details the overwhelming scope of the problem of poison and toxins that are found within our public schools here in the School District of Philadelphia. It also does a good job of calling out the decades of inaction around this issue which school communities have historically been ignored for bringing up. School District of Philadelphia. (2018, November) School District of Philadelphia Lead Report for The U School. This report is the the official document that the School District of Philadelphia decided to send out to parents regarding its decision not to take action on 8.4ppb lead levels in the kid’s drinking and cooking water. Carson, R., Kelsh, N., & Lear, L. J. (2017). The sense of wonder: A celebration of nature for parents and children. New York, NY: Harper Perennial. The thesis of this book is that, if children are raised with a feeling of connectivity and mutual admiration with the environment, they will be much more likely to respect it and care for it as adults. This concept is the driving force behind the inclusion of field trips to local bodies of water in the unit. Cadena, M. D. (2010). Indigenous Cosmopolitics in the Andes: Conceptual Reflections beyond “Politics”. Cultural Anthropology, 25(2), 334-370. The article points out that people who live near and around and in environments are a part of those environments themselves, in such a way that the collective is the full and real entity, and the individuals in the environment without the collective as a whole do not equal the entity itself. It cannot be separated. Therefore, my students are a part of the waterways of Philadelphia, and vice versa. My students are cared for by the water in this city, and they play a part in caring for the water too. Nielsen, Lisa. “High School Doesn’t Have to Suck – Chris Lehmann.” Lisa Nielsen: The Innovative Educator, TEDxPhilly, 16 Feb. 2011, theinnovativeeducator.blogspot.com/2011/02/high-school-doesnt-have-to-suck-chris.html. “What if high school wasn’t preparation for real life, instead it was real life?” Quote grabbed from this video. Chris Lehmann was an innovator in the field of project based learning in Philadelphia in the mid to late 2000s. I went to one of his schools, SLA Center City, and it has impacted my pedagogy tremendously. Kephart, Beth. Flow: the Life and Times of Philadelphia’s Schuylkill River. Temple University Press, 2014. Some poetry from this will be used as inspiration as we are cohabitating and spending time with water and documenting our own thoughts, feelings, and observations. “About the Friends.” Tinicum, Heinz Wildlife Refuge at Tinicum, www.friendsofheinzrefuge.org/tinicum3.htm. Some information on the volunteers who work to keep the wildlife refuge clean and operational. “Schuylkill River & Urban Waters Research Corps Archive.” Schuylkill Corps, Penn Program in Environmental Humanities, 2016, schuylkillcorps.org/. This is a site Professor Wiggin introduced us to, which aims to document all activity and projects related to our city’s waterways. “The Eastwick Living History Project.” Schuylkill Corps, Penn Program in Environmental Humanities, schuylkillcorps.org/exhibits/show/eastwick-oral-history-project/urban-renewal. This is a section of the Schuylkill River Corps site that specifically focuses on the Eastwick residents of Philadelphia. It documents their experiences and struggles for justice and visibility in an unfair and botched housing plan by the city. “Mining in Peru: Human Rights Abuses Heard at US Congress.” War on Want Fighting Global Poverty, War on Want, 18 Dec. 2015, waronwant.org/media/mining-peru-human-rights-abuses-heard-us-congress. This is a quick report about a Peruvian indigenous fight against a gold mine being installed on their land and their water being threatened. “Chris Long Waterboys.” Waterboys, The Chris Long Foundation, waterboys.org/player/chris-long/. This foundation is the kind of outsider, savior-type of ngo that I don’t usually align with. However, Chris Long is one of the Philadelphia Eagles, and he has proved himself to be a really caring and politically aware celebrity and role model for kids. Including a group like this, something that is familiar to my students that they can relate to, helps to make all of the groups more accessible as well. “Welcome to Clean Water Action, California!” Clean Water Action, 20 Dec. 2017, www.cleanwateraction.org/features/welcome-clean-water-action-california. This is a group based out of CA that fights for clean water and against policies passed by the Trump administration that roll back regulations to stop water pollution. They do a good job of pointing out the racialized nature of America’s most polluted water. Chariton, Jordan. “Standing Rock Protectors Brutalized By Cops In Standoff.” YouTube, The Young Turks, 2 Nov. 2016, www.youtube.com/watch?v=G4-s1K7qsEY. This is a video that shows how some of the Standing Rock protesters fought for their right to clean water during the DAPL crisis. The inclusion of these videos was a difficult choice for me. That journalist, Jordan Chariton, was accused of sexual harassment and fired from the publishing news channel, The Young Turks. Unfortunately, very few news stations bothered to cover the Standing Rock story, it was largely ignored, and almost no news stations send journalists to put boots on the ground and do active journalism. These are some of the only two videos I could find with real reporting. I chose to include these videos despite the sexual harassment, and that is a choice that each teacher will have to make when deciding whether or not to include these videos. I think the whole dilemma is just a testament to how little the media has paid attention to environmental issues and indigenous issues. Chariton, Jordan. “Oil Police Cause Health Problems For Unarmed Water Protectors.” YouTube, The Young Turks, 2 Dec. 2016, www.youtube.com/watch?v=AVB7U6g2kgg. This is a video that shows how some of the Standing Rock protesters fought for their right to clean water during the DAPL crisis. The inclusion of these videos was a difficult choice for me. That journalist, Jordan Chariton, was accused of sexual harassment and fired from the publishing news channel, The Young Turks. Unfortunately, very few news stations bothered to cover the Standing Rock story, it was largely ignored, and almost no news stations send journalists to put boots on the ground and do active journalism. These are some of the only two videos I could find with real reporting. I chose to include these videos despite the sexual harassment, and that is a choice that each teacher will have to make when deciding whether or not to include these videos. I think the whole dilemma is just a testament to how little the media has paid attention to environmental issues and indigenous issues. Ruderman, Wendy, et al. “Philadelphia School Kids Will Get Added Protections from Lead Paint Perils.” Https://Www.philly.com, The Philadelphia Inquirer, 16 Dec. 2018, www.philly.com/news/philadelphia/lead-paint-philadelphia-schools-protections-toxic-city-20181213.html. This is an article that details the school district’s supposed response to the lead paint issues in our schools. This response came as a result of a student who got serious brain damage from eating lead paint chips that were falling onto his desk. As any teacher from Philadelphia knows, the deteriorating building issue has been going on for decades upon decades, and the district and the local and state government haven’t done a thing about it. It wasn’t until a child’s life was threatened on a massive public scale that they decided to pay attention and commit to some remediation. However, as any Philly teacher also knows, this “remediation” has not happened at all. My school alone is filled with chipping paint on ceilings and walls in classrooms all over the building. Mold grows in certain classrooms in my buildings, the pipes are wrapped in asbestos, the pipes have lead, the drywall is crumbling onto desks.