Author: Renae Curless

School/Organization:

George Washington Carver School of Engineering and Science

Year: 2017

Seminar: That's My Song! Musical Genre as Social Contract

Grade Level: 6-8

Keywords: African American History, African American literature, Civil Rights Movement, integration, little rock, melba patillo beals, Music, poetry, racism, segregation

School Subject(s): African American History, African American Literature, English, Social Studies

“I continue to be a warrior who does not cry but instead takes action. If one person is denied equality, we are all denied equality.” – Melba Patillo Beals

This unit, originally designed for eighth grade English, uses Melba Patillo Beals’s memoir Warriors Don’t Cry as the anchor text. Warriors Don’t Cry is Beals’s story of being one of the Little Rock Nine, the nine African American students chosen to integrate Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1957. There are two abridged and unabridged copies of the text; the abridged is more appropriate in length and depth for middle school, while the unabridged version could be appropriate for a high school English or Social Studies class. This unit seeks to make connections between Beals’s story, music and other artistic works, and the larger Civil Rights Movement. There are several opportunities to incorporate informational texts, poetry, stories, and music.

Did you try this unit in your classroom? Give us your feedback here.

Focusing on the special role that music played in the Civil Rights Movement provides a new angle that is not merely re-teaching “the struggle.” It is important that students of all backgrounds see how others successfully fought against oppression, and to use that to analyze where we still need to go in moving our society forward. Although the anchor text is primarily set in 1957-1958, the works incorporated in this unit span from 1900 to today. Because the unit incorporates music, poetry, art, and nonfiction, it links together several different disciplines and genres to allow students to make significant connections and practice key skills. Some of the key skills for middle school and early high school students are using evidence to make inferences about the text and writing for a variety of audiences and purposes; this is found in this unit, but it is flexible enough that it can be adapted to students with varying ability levels. Many students may not think critically about the songs they listen to every day or what in the past inspired some of their favorite artists today. By providing students with a critical lens with which to analyze one seemingly ordinary aspect of their world, they will become more critical consumers and thinkers. Students who are resistant to analyzing literature may not think twice about reading song lyrics and discussing what they mean; similarly, many students might be surprised at how much meaning is behind the songs they sing and dance to every day! Warriors Don’t Cry is one of my favorite books to teach. There are a few different levels of understanding and connection: what it means to be a teenager in the 1950s in a segregated city, identity as a black teenager, and the almost-universal experience of being a teenager. There are ample opportunities to discuss the text, history, and our lives, as well as to look towards the future and think about how we make change when people are so resistant. The unit begins with a media investigation with poetry, music, and art spanning from 1907 to 1971. Students analyze W.E.B DuBois’s poem Song of the Smoke, which speaks of pride in being black; as well, they analyze Sterling Brown’s 1931 poem Strong Men. These poems begin the lead-up to World War II, which could be identified as a turning point in the Civil Rights Movement. The painting “‘Crute’ Drill” examines the segregation of the Armed Forces in WWII; when black soldiers returned from fighting for others’ freedom overseas, they were unhappy with the separation and injustice they faced at home. The next large event this unit discusses is the murder of Emmett Till, a teenager visiting family in the South that was kidnapped, brutally beaten, and murdered for allegedly whistling at a white woman. His mother, Mamie Till, held an open-casket funeral so that the world could see what was done to her son. This made several activists realize they could not wait anymore; soon after, Rosa Parks was arrested for sitting in the white section of a segregated bus. According to her memoir, when Melba Patillo Beals’s family found out that she had volunteered to integrate Central High School, they were furious and terrified. Melba and the eight other students faced daily torment, harassment, and abuse when they entered their school every day. At one point, Melba and the others acknowledge that their integration is not about them individually getting an education; it is about making a statement and trying to make a change for the future. As Melba reflects on her decision to attend Central, she knows that Little Rock, AK will never be like the integrated haven of Cincinatti, OH, where she visited her extended family one summer. It is this that inspires Melba to be one of god’s warriors. After her junior year at Central, Melba attends the rest of high school and college in California; the memoir closes with her and the eight returning to Central years later for a celebration in their honor. As Melba ascends the stairs to the school, she has flashbacks and feels her stomach tightens; however, the African American student body president opens the doors of the school and welcomes her to Central High. Although the anchor text ends before many of the major events in the Civil Rights Movement took place in the 1960s, the beauty of music and literature is that listeners and readers make their own connections. The unit should include an in-depth examination of the folk song “We Shall Overcome,” and its history. Adapted from a gospel song and sung by tobacco workers in the 1940s, the song spread as a protest song by Pete Seeger and others who published the song and taught it at rallies. It eventually gained momentum, and was quoted by Lyndon B. Johnson and Martin Luther King, Jr. days before his death. The song is still sung today and is a connection to the past. Other notable artists teachers can include in their units are Nina Simone and Sam Cooke, specifically used in this unit, Billie Holliday, Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, James Brown, Rick James, Chaka Khan, Donnie Hathaway, The Temptations, Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder, NWA, Public Enemy, Nas, Notorious BIG, Tupac Shakur, Lauryn Hill, and Kendrick Lamar.

This unit is intended for 8th grade students, but could be adapted for 7th or 9th grade students. Students are taught in a block schedule, and spend about 6 periods each week reading and analyzing the anchor text. Essential questions and objectives are as follows: Essential Questions: Objectives:

The unit will be centered around the anchor text, Warriors Don’t Cry by Melba Patillo Beals. Students will engage in a variety of small-group and whole class discussion at various points in the text to discuss the anchor text as well as different poems, short stories, nonfiction texts, and songs. Discussion is a large part of this unit and text. Although they are not detailed in the classroom activities, recommended discussions are Socratic Seminars. Students should submit discussion questions and topics in advance to be selected with the teacher’s questions. Students should also be encouraged to take the questions they see in the direction they want to discuss, and to tackle all sorts of issues. Students should analyze the language of the text, characterization, their personal connections, connections to history and other classwork, and “eternal questions” that have no clear answer. An important part of this unit is reflection and personal connection. Students will respond directly to the text in addition to their analysis to draw personal meaning from the different songs and texts we read. They can do this informally through brief reader response journals, or more formally through reflections and discussion. Students will also analyze the lyrics, structure, and musical composition of different songs. Each week of reading will be paired with a genre: folk, soul, rock&roll, funk, and hip-hop. These should be taught in order to align the evolution of genres in the Civil Rights Movement with the progression of Melba’s story. Teachers can break up their reading schedule depending on their class’s schedule and ability level.

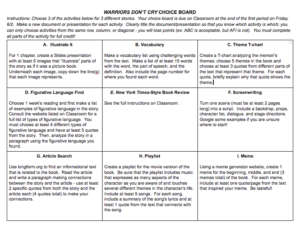

Students will complete several exercises and engage in discussion throughout the unit, and will complete an analytic research paper on music in the Civil Rights Movement. Teachers can complete a few other medium-scale projects with their students: Depending on the students’ familiarity with research, the teacher should provide varying levels of support during the research project. As well, the teacher can decide if they would like the students to complete a research project on a specific time period, genre, or artist. However, the research paper should be a historical argument; what was the role of [student topic] in the Civil Rights Movement? Classroom Activity 1: Warriors Don’t Cry Media Investigation As pre-reading, students will investigate a few different types of media from different stages of the Civil Rights Movement. This will give students a foundation of artistic works with which to begin the text. Prior to this activity, students should activate their prior knowledge of the Civil Rights Movement by brainstorming what they already know or have heard of as it relates to this time period, both before and after. Students will rotate among three stations: poetry, artwork, and music. At each station, students review the materials in the folder, and answer the questions as a group. When they finish at each station, students should review the debrief questions and begin to jot down thoughts to share in discussion. The teacher should be available as a resource to define words, terms, and help students make connections. Station 1: Poetry The goal of this station is for students to read poems from lead-up to the Civil Rights Movement. The two I have selected are Song of the Smoke by W.E.B. DuBois and Strong Men by Sterling Brown. Both were published before the 1950s; Song of the Smoke was published in the early 1900s and Strong Men in 1931. Station 2: Artwork At this station, students will examine three pieces of artwork from different stages of the Civil Rights Movement. The first is Crute Drill, a response to the segregated armed forces in World War II, the second is Behold Thy Son, painted in response to the lynching of Emmett Till and his mother’s decision to hold an open casket funeral, and the third is Unite, a mixed-media piece from the 1970s. Students will examine a slideshow of the artwork and background information, and use that to break down the components of each piece in order to analyze them and make connections among them. Station 3: Music Students will listen to This Little Light of Mine by Sam Cooke and Mississippi Goddam by Nina Simone. Teachers should provide copies of the lyrics for students to follow along. Students will analyze the songs when they are done listening. Debrief When students have finished all three stations, they should begin to jot down thoughts to the debrief questions. Students do not need to write in complete sentences; they just need to be ready for discussion. When students have had adequate think time, they should discuss the different pieces they analyzed, make connections, and think ahead to their upcoming reading. Classroom Activity 2: The Problem We All Live With Either as pre-reading or about halfway through the reading, students will analyze school segregation before, during, and after the events in Warriors Don’t Cry by using Norman Rockwell’s “The Problem We All Live With” and This American Life’s podcast episode “The Problem We All Live With.” The podcast details integration in Missouri in 2014. Warm-up: Ask students to take out a piece of paper and write down everything they notice about the projected painting. Be sure to stress that no detail is too small and they should not share anything they think they know about the painting yet – they are just writing down as much as they can about the painting. Project Norman Rockwell’s The Problem We All Live With on the board and give students about 3-5 minutes to take notes. When all students are done, have each student go to the board one at a time and point out one thing they notice about the painting. When all students have shared, or everything has been pointed out, ask students to draw conclusions about the painting. What do students already know about this painting? What do the details mean when “added up?” Activity: When students listen to the podcast, they should write down or highlight (depending on resources) lines that evoke any sort of emotion – happiness, sadness, anger, etc. Students do not need to explain or write why they wrote down the line or idea. Distribute transcripts of the podcast (This American Life’s “The Problem We All Live With” by Nicole Hanna-Jones) and begin listening. Stop periodically to discuss. Explain the discussion technique to students (Save the Last Word for Me). Randomly choose one student to share one line or idea that evoked emotion; the student should not yet share why they chose the line. Then, choose 3-5 students to respond to the line the student mentioned. While you can choose random students to respond, this activity works best if students already have things in mind as responses. When all students have shared, the original student should share why they originally chose their line or idea. Continue with the podcast or choose another student to begin another Last Word discussion. Debrief: Ask students to share out lines that they want to talk about or add on to; students should make connections between the text and the podcast – what work still needs to be done? What have we accomplished? How do we make change? Classroom Activity 3: Moving Forward This activity, paired with the last chapter and epilogue, will extend our knowledge of what happens to Melba and the others at the end of the memoir and make connections to rap and hip hop as types of activism. Students will research hip hop artists and rappers from different eras of hip hop, analyze their lyrics, and present their findings to the class. This lesson will take 1-2 class periods depending on class length. Warm-up: Students can journal to a specific prompt or their own, take a reading quiz, or teachers can lead an informal discussion clarifying the chapters. Activity: Students should be broken up into 3-6 groups depending on class size and teacher interest. Each student will be assigned a five-year chunk or decade starting from 1980. Students will begin by researching the artists and music of their time period. From there, they will select one artist, their album, and one song to analyze and present to the class. Students should analyze their lyrics as they would a poem – either line by line or stanza by stanza. Students should then prepare a brief presentation for their class that include: a brief overview of musical artists and issues in their time period, more specific information on the importance of their artist and album, a playing of the song, and a breakdown of the lyrical analysis. Debrief: Once students present, ask them to share their conclusions with the class. How has music in the Civil Rights Movement evolved? What is similar or different? Do students feel as though music helps connect them with other people and social movements? Considerations: Teachers can provide a resource list or specific artists for students to research depending on their level of familiarity with the research process. As well, to cut down on presentation time, students can choose a 30 second-1 minute chunk of the song to present to their classmates. This activity can be formal or informal – formal presentations could be assessed using a rubric, while informal presentations could be assessed on how students used their prep time and how well they stimulate discussion.

Resources for Teachers: George, Charles. Living through the Civil Rights Movement. Detroit: Greenhaven, 2007. Print. This collection has articles, speeches, and narratives from 1950 through the 1960s. It is useful for teacher background information as well as for reproducibles for student analysis. Rabaka, Reiland. Civil Rights Music: The Soundtracks of the Civil Rights Movement. Lanham: Lexington, 2016. Print. Similar to Rabaka’s hip hop book, this book breaks down several different genres, as well as more technical musical analysis skills. Rabaka, Reiland. The Hip Hop Movement: From R & B and the Civil Rights Movement to Rap and the Hip Hop Generation. Lanham: Md., 2013. Print. This book provides a comprehensive overview of music from the 1940s and its evolution to modern rap and hip hop. It includes information about several different artists, as well as an understanding of the importance of different music in different time periods in the Civil Rights Movement and today. Sanger, Kerran L. “When the Spirit Says Sing!” the Role of Freedom Songs in the Civil Rights Movement. New York: Routledge, 2015. Print. This book provides a discussion of freedom and folk songs instrumental in the Civil Rights Movement. It is useful for teachers to review the analysis of specific songs as well as their role in the activists’ lives in preparing to help students analyze song lyrics. Some sections could also be useful for students’ own analysis. Student Texts: Beals, Melba. Warriors Don’t Cry: A Searing Memoir of the Battle to Integrate Little Rock’s Central High by Melba Pattillo Beals. Seattle, WA: BookRags, 2011. Print. This is the anchor text for the unit; there is both an abridged and unabridged version available. Classroom Resources: Brown, Sterling. “Strong Men.” The Making of African American Identity. (Print). Cooke, Sam. This Little Light of Mine. Sam Cooke. 1964. CD. The Sam Cooke song for the media investigation. Driskell, David. Behold Thy Son. 1956. National Museum of African American History and Culture, Washington, DC. National Museum of African American History and Culture. Smithsonian. Web. 30 June 2017. Another painting for the media investigation. Eyes on the Prize: Awakenings. Prod. Henry Hampton. PBS, 1987. DVD. This is the first episode in the PBS series “Eyes on the Prize.” “Awakenings” provides an overview of the beginnings of the Civil Rights Movement from after WWII to the early 1960s. It does include video and interviews about the Little Rock Nine, so some parts could be skipped. Hannah-Jones, Nicole. “The Problem We All Live With.” Audio blog post. This American Life. Podcast for The Problem We All Live With classroom activity. Johnson, William H. “Crute” Drill. 1942-1944. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC. Smithsonian American Art Museum Renwick Gallery. Web. 30 June 2017. One of the paintings for the pre-reading media investigation. Jones-Hogu, Barbara. Unite. 1971. National Museum of African American History and Culture, Washington, DC. Oh Freedom! Web. 30 June 2017. One of the paintings for the media investigation. Rockwell, Norman. The Problem We All Live With. 1964. Norman Rockwell Museum, Stockbridge, MA. Norman Rockwell Museum. Web. 30 June 2017. Norman Rockwell’s painting “The Problem We All Live With.” Although it was painted after the integration at Central, it is a useful discussion piece and warmup for students. Simone, Nina. Mississippi Goddam. Verve, 2007. CD. Nina Simone’s song for the media investigation.

Unit objectives, questions, activities, and assessments are aligned with the PA Common Core ELA Grade 8 standards. Reading Informational Texts: CC.1.2.8.B Cite the textual evidence that most strongly supports an analysis of what the text says explicitly, as well as inferences, conclusions, and/or generalizations drawn from the text. CC.1.2.8.C Analyze how a text makes connections among and distinctions between individuals, ideas, or events CC.1.2.8.F Analyze the influence of the words and phrases in a text including figurative, connotative, and technical meanings, and how they shape meaning and tone. CC.1.2.8.I Analyze two or more texts that provide conflicting information on the same topic and identify where the texts disagree on matters of fact or interpretation. Reading Literature: CC.1.3.8.B Cite the textual evidence that most strongly supports an analysis of what the text says explicitly, as well as inferences, conclusions, and/or generalizations drawn from the text. CC.1.3.8.E Compare and contrast the structure of two or more texts and analyze how the differing structure of each text contributes to its meaning and style. Writing: CC.1.4.8.C Develop and analyze the topic with relevant, well-chosen facts, definitions, concrete details, quotations, or other information and examples; include graphics and multimedia when useful to aiding comprehension. Speaking and Listening: CC.1.5.8.A Engage effectively in a range of collaborative discussions, on grade-level topics, texts, and issues, building on others’ ideas and expressing their own clearly.

WARRIORS DON’T CRY PRE-READING Answer these questions with your group. Be ready to discuss these pieces separately and as a whole. Poetry Strong Men by Sterling Brown ____________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________ The Song of the Smoke by W.E.B. Du Bois ____________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________ Artwork Songs Mississippi Goddam by Nina Simone ____________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________ This Little Light of Mine by Sam Cooke ____________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________ DEBRIEF Discuss these questions with your group and be ready to participate in discussion – jot down some answers! Artwork Background Info “Crute” Drill by William H. Johnson, 1942-1944 —————————- Behold Thy Son by David Driskell, 1956 “[Mamie Till] also distributed a photograph of his mutilated corpse to the press, asking them, “Have you ever … had [a son] returned to you in a pine box, so horribly battered and water-logged that someone needs to tell you this sickening sight is your son—lynched?” Although the white media refused to publish the photograph in its coverage of the murder, the gruesome image was widely circulated by some African American periodicals, including Jet magazine. Till’s mother later explained why she decided to put her son’s body on public display: “They had to see what I had seen. The whole nation had to bear witness to this.” Driskell decided to paint Behold Thy Son because he “was well aware of the power of social commentary art and its use to stir the consciousness of a people.” Using heavy, dark outlines and bright highlights so that his painting resembles a stained glass window, Driskell depicted a figure with his arms outstretched as if crucified. A woman holds out the body, embracing and supporting it—much like religious sculptures and paintings of the Pieta—but also offering it uncomfortably close to the viewer, so close that its limbs are severed by the edges of the canvas. Although Driskell provided details suggesting Till’s battered body and face, the sacrificial theme and religious symbols transcend the event. The painting connects those who have suffered injustices in order to save others. Driskell explained that he intended to portray “the sacrifice of many young lives from Christ to Till.” —————————- Unite by Barbara Jones-Hogu, 1971 By combining strong silhouettes, limited colors, and bold lettering, Barbara Jones-Hogu not only prints her message, “UNITE,” but also makes its meaning palpable. As the word repeats in vivid colors and angular forms above a series of figures, it seems to echo and grow loud. The figures below enact the message. Their rows of similarly raised fists and solemn faces, many in profile, form a rhythmic pattern atop a single, undifferentiated black mass—their unified body. This print conveys the purpose, intensity, and energy of the African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists (AfriCOBRA), a coalition of artists who formed in the late 1960s with the express purpose of defining and modeling a uniquely black aesthetic in the visual arts. AfriCOBRA coalesced within the broader Black Power movement, which gained popularity among many African American activists in the 1960s and early 1970s. Advocates of Black Power argued that racial pride, political resolve, and militant unity were the best means for upturning the status quo—the situation as it currently exists. The raised, clenched fists in Jones-Hogu’s print, which many considered the Black Power salute, and the Afro hairdos, which many of the figures sport, signify these ideals. Consciously defiant, they symbolize the group’s self-determinism and their insistence on radical change. In this print, African elements include the Afros and the ankh, an ancient Egyptian symbol, which one woman wears. These symbols provided a shared source of identity that compelled many to dedicate themselves to the freedom struggle, or as Jones-Hogu urges, to unite.

“Crute” Drill

Behold Thy Son

Unite

What colors are in this painting?

What style of artwork do you think this is? (Do the people depicted look realistic, what kinds of colors are used, etc) How is this painting style different from the other two?

What is the painting about?

WARRIORS DON’T CRY BODY BIOGRAPHY In a group, you will create a body biography drawing for one character (or composite character) in Warriors Don’t Cry. A body biography is a visual and written portrait of a character in a written work. Body Biography Requirements: Considerations: Placement: Carefully consider the placement of traits on the body; some ideas are below: Color: Refer to the universal symbol packet to find colors that represent your character Virtues and Vices: People have contradictory personality traits – how are these represented in your character? How do they represent themselves, and how are they seen by others? Symbols: What objects do you associate with your character, either mentioned in the text or on your own? Changes: How does your character change throughout the text? Formula Poems: Easy, effective “recipes” for original texts; see examples FORMULA POEMS I Am (as if the character were speaking) *1st Stanza I am (two special characteristics the character has). I wonder (something the character is curious about). I hear (an imaginary sound). I see (an imaginary sight) I want (an actual desire). I am (the first line of the poem repeated). *2nd Stanza I pretend (something the character pretends to do). I feel (a feeling about something imaginary). I touch (an imaginary touch). I worry (something that really bothers the character) I cry (something that makes the character very sad). I am (the first line of the poem repeated). *3rd Stanza I understand (something the character knows is true). I say (something the character believes in). I dream (something the character dreams about). I try (something the character really make an effort about). I hope (something the character hopes for). I am (the first line of the poem repeated). Where I’m From (use George Ella Lyon poem as a model) Focus on how your character would write this poem. Cinquain Diamante Tanka Poem for Two Voices Persona Poem Haiku (if several settings are referenced) RUBRIC

4

3

2

1

Visual (x2)

Visuals and placement represented a thorough and complex understanding of the character; choices were interesting and well-thought-out

Visuals and placement represented an understanding of the character; choices made sense with the character

Visuals and placement did not make sense for the character or represented an incomplete understanding of the character

Visuals and placement do not give any indication of understanding of the character

Original Written Work (x2)

Work was creative, thoughtful, and well-written; work showed insight into the character and could be used to spark discussion

Work was creative and thoughtful; work showed some insight into the character and understanding of their role

Work is uninteresting and skims the surface of the character

Work is incomplete or references only one aspect of characterization

Quotes

Group incorporated at least 5 quotes; quotes are from different parts of the text; quotes are interpretable and show insight into the character

Group incorporated at least 5 quotes; quotes are from different parts of the text; quotes provide summary or a basic understanding of characterization

Group incorporated 2-4 quotes; quotes are from the same part of the text; quotes provide summary or a basic understanding of characterization

Group incorporated few quotes; quotes provide little to no understanding of the character or their characterization

Neatness

Project is neat, well-colored, and easy to read; it is obvious the group spent time on the project

Project is neat but could use more polish

Project is sloppy in some parts or uncolored; it is difficult to read parts of the biography

Project is sloppy and uncolored; it is difficult to read parts of the biography

Teamwork

All group members worked efficiently and were able to work through any disagreements and distractions

Group used most class time effectively; some intervention or redirection needed

Group needed several interventions but was able to complete a final project

Group members accomplished nothing due to disagreements

WARRIORS DON’T CRY PRE-READING WEBQUEST Follow the links to answer each question. Answer all questions in complete sentences for full credit. No link – Warm-up questions (google if you don’t know the answer) The War: At Home (http://www.pbs.org/thewar/at_home_civil_rights_minorities.htm) Brown v. Board of Education (http://www.pbs.org/wnet/supremecourt/rights/landmark_brown.html)