This socio-scientific issue unit takes an inquiry project-based approach to the phenomena of robotics and disability. Students are invited to think of how our society accommodates and services individuals with different kinds of functioning and impairment via assistive technologies and other approaches. They authentically use the engineering design process to attempt to solve a real case study’s problem, and actually build, test, and rebuild a product. Creativity, research, collaboration, reflection, and communication are all integral components of this work. Students investigate various aspects of robotic technology and share their understandings with each other. They explore specific health problems as well as the larger societal issue of health insurance and disability accommodations. They use argumentation and communication practices to elucidate their own opinions and take action on disability issues. By the close of this unit, students will likely have internalized an anti-ableist lens. They will know that accessibility, in its goal to foster meaningful inclusion for all people in society, is an important manifestation of justice.

Dr. Michelle Johnson specializes in engineering robotics for stroke rehabilitation, and her course has been very impactful for me. The principal elements at work when it comes to physical therapy robots are expertise with anatomy, diagnostics, programming, and fabrication. But at the root of this topic are empathy and optimism: the people who are working in the forefront of this field care deeply about equity and problem-solving, for disabled individuals, the people who care for them and the communities they belong to. They want to meet a human need that is real and important: self-efficacy, through genuine involvement in one’s surroundings. Our in-class lectures began by clarifying the relationship between disability and function, in context. Health-related challenges due to chronic illnesses and disabilities significantly impact individuals’ quality of life (including life expectancy) and societal participation. The World Health Organization reports that noncommunicable diseases (including cardiovascular diseases, cancer, diabetes, and chronic respiratory diseases), now account for 75% of all global deaths.[1] These conditions disproportionately affect low- and middle-income countries, where healthcare infrastructure may be most limited. According to the NCD Letter Letter to National Advisory Council on Minority Health and Health Disparities, many survivors of such diseases in America live with long-term physical and mental well-being impairments, exacerbating social and health disparities, especially where therapy and assistive services are biased or scarce.[2] The correlation between per-capita healthcare spending and “Disability Adjusted Life Years”[3] is well-demonstrated in the following chart (see figure 1). The more we spend, the longer people live. Of course, preventative care and physical therapy contribute to better health and financial outcomes in the long run. Disability is more than a medical condition. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health provides a model that demonstrates an interaction between health conditions, body functions, personal activities, participation in social life, environmental factors, and personal factors.[4] It follows that impairments in body structures (for example, because of a stroke) may lead to activity limitations and participation restrictions, but these can be mitigated through targeted interventions. Pain points are relevant, and must be considered while a person aims to return to “normal.” The goals of rehabilitation are to increase someone’s ability to interact with the real world on their own or with an assistive device by reducing impairments, enhancing capacity, and ultimately improving their lives. If a therapy approach is not effective in these goals, then the plan must be adjusted. Capacity refers to a person’s innate ability to perform a task without support, while performance refers to what they can actually do in real life, often with the aid of therapy or technology. Rehabilitation clinicians play a key role in assessing both, often relying on models of disability to guide decisions. For example, the Timed Up and Go (TUG) test[5], the Box and Blocks test[6], and Grooved Pegboard test[7] each evaluate upper or lower limb function, using speed and various aspects of movement (stability, gait, stride, dexterity, and dropped pegs, respectively). Cognitive assessments like the Stroop Test[8] and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment measure mental performance in terms of either cognitive interference or “short term memory, visuospatial abilities, executive functions, attention, concentration, working memory, language, and orientation to time and place.”[9] These tools generate quantitative data that can be compared against normative populations, aiding diagnosis, therapy planning, and insurance approval for devices. According to Stroke Rehabilitation, the predictions physicians make on their own are not as accurate as the predictions they could make using research evidence (prognostic studies or prediction modeling studies). This may be because studies use or evaluate multivariable prediction models, and must test representative cohorts, standardize the measurement of predictors and outcomes, and conduct external evaluations.[10] Artificial intelligence is working its way into stroke analysis, as well. Rem Azar (a PhD candidate in Dr. Johnson’s lab), is currently using brain imaging to correlate specific dead neural tissue regions to physical and cognitive functioning. Machine learning might help to streamline this process (algorithms can diagnose brian scans and make predictions and treatment recommendations[11]), but a therapist is still necessary to employ best practices. Multifaceted analysis can lead to better plans. Clearly, clinical practice is benefitted by the use of technology. Assistive Technology (AT) includes any tool, device, or service that helps individuals perform tasks they would otherwise find difficult or impossible. These range from low-tech aids like canes to high-tech devices like robotic limbs or even EEG-driven interfaces, which translate brain signals into coded commands[12]. AT can be assistive, adaptive, or rehabilitative. Devices may be load-bearing or weight-bearing, passive or active, wearable or stationary. Their primary aim is to increase the user’s independence and participation across environments (home, work, community).[13] This diversity of devices aligns with the Human-Activity-Assistive Technology (HAAT) model[14], which emphasizes the interaction between user, device, task, and context. Despite the promise of AT, many devices are abandoned because they are not a good fit for the client. To meet this need, the Matching Person and Technology (MPT)[15] framework aims to achieve user-device compatibility. Effective devices must not only work well but also align with user preferences, cognitive abilities, daily routines, and social environments. The steps in this framework are to 1) establish goals and alternative goals, and list intervention and technologies needed, 2) identify satisfaction with past technologies used and interest in different technologies, 3) compare consumer and professional opinions on the technology under consideration, 4) discuss potential issues with the technology that was chosen, 5) formulate strategies and an action plan to mitigate these issues, and 6) commit the plan to writing, which also serves as documentation for funding or other purposes. Appropriate strategies on the front end of AT choice can make all the difference in outcomes. The origin story of AT happens in the lab, and many minds come together to develop products. Design thinking (particularly methods from IDEO)[16] calls for ideation, empathy, and iteration. For instance, in a case study we conducted in class involving a 13-year-old girl with cerebral palsy in rural Ghana, considerations for AT included portability, solar-powered charging, and toy-like appeal for fine motor skill development. Most importantly, our client wanted to communicate more easily. We were encouraged to use the HAAT model[17] to come up with as many ideas as possible, following these rules: In the end, we converged into two groups with two separate designs to carry out and then convince funders with an “elevator pitch.” In real time, we saw the need for practical, user-centered, culturally appropriate, and playful tools that offer therapeutic benefits. It is worth it to mention the methods we used to practice the engineering design process in class. The first way we worked on our wheelchair-compatible devices was to sketch individual ideas and share them (see figure 2, plan by Alyson Iovacchini). Next, Dr. Johnson grouped us based on the commonalities of our visions. We then agreed on a single cohesive plan for each group, and worked together to build triwall cardboard prototypes, using steak knives, x-acto blades, and hot glue. This is one way that her university students build their models; it was low-risk from both a time and materials perspective, and greatly helped to test size compatibility and ease of manipulation. As the global demand for therapy outpaces available clinical resources, especially in rural or under-resourced areas, robotic rehabilitation emerges as a scalable alternative. Robotics can deliver repetitive, data-driven therapy that promotes neuroplasticity and recovery post-stroke or injury: “they can maximize afferent input from peripheral joints and provide task-specific stimulation to the central nervous system to promote functional recovery.”[19] Robots learn therapists’ and patients’ movement trajectories through kinematics and haptics, and may be trained using machine learning based on therapists’ interventions.[20] Shafagh Keyvanian (another one of Dr. Johnson’s PhD students) explained that they offer both passive (guided motion) and active (resistance training) modes. However, robots still lack the human insight necessary to interpret “intent” or make nuanced decisions, presenting challenges in replicating therapist behavior. Right now, they are limited by human abilities in programming. During our visits to the GRASP Lab at Penn and the Rehabilitation Labs at Penn Medicine, we learned that autonomous systems continue to evolve by analyzing muscle signals through electromyography (a diagnostic test that assesses the health of muscles and the nerve cells that control them), ultrasound, and electroencephalogram (a test that measures and records the electrical activity of the brain). There was a small motion, grip, and pressure sensing setup for early intervention in babies with cerebral palsy. There were “serious games” set up for people to play against their own best score, or each other, and improve their strength, smoothness, and speed while playing. There were 360° video cameras that could notice range of motion, spasticity, and balance much better than the human eye. Robots are already assisting physical therapists in creating complex models of motion and intent. In the words of Len Calderone, since robots can collect so much more accurate data, but lack human touch and nuances, they can only “augment a physical therapist’s job and not replace it.”[21] Despite technical advancements, effective robotic therapy must integrate seamlessly into a user’s life, requiring careful consideration of design, context, and individual differences, and for that we need medical professionals. Even the best-designed technologies can fall short if users cannot access them. Geographic, financial, and institutional barriers, especially in rural settings, often limit access to necessary care and technology. Policies like the Americans with Disabilities Act[22] (ADA) and the Rehabilitation Act of 1973[23] aim to improve access, but implementation gaps remain. Insurance policies, funding availability, and healthcare infrastructure significantly affect the adoption and continued use of AT. Devices that are not covered, or that require expensive customization, may be deemed unusable regardless of their effectiveness. Since context was so important throughout our course, I must mention that at this time, the United States has withdrawn support for most formerly USAID-funded programs.[24] People with both communicable and noncommunicable diseases all over the world have depended on these clinics and the resources they provided for their livelihood. The Priority Assistive Products List explains that even before this new status quo, “People from the poorer sectors of society frequently rely on donations or charitable services, which often focus on provision of large quantities of substandard or used products.” Now, the global nongovernmental organizations that did this good work are even more overburdened, and are turning people away. We are also now waiting to see if the new federal budget will cut Medicare funding.[25] Proponents of this budget claim that states will be responsible for coverage. Healthcare workforce shortages are dangerously low, particularly in rural areas (where they also lack internet access and therefore cannot use telehealth services), and as our population ages, this issue will only grow in urgency.[26] Given that we seem to be under emergency, it may seem that the idea of robotics in physical therapy is impractical or fantastical. Quite the opposite: technology can solve our human services problem and be more cost-effective in the long run. Drones can deliver medicine to hard-to-reach places.[27] 3-D printers can produce medical devices and personalized AT.[28] Therapeutic robots can support diagnostics and “hands-on” practices. AI scribes can convert physician’s notes into database entries quickly and correctly.[29] Software can inventory medical supplies and automatically re-order them when needed.[30] Better internet access can bridge the gap between no access and virtual access until help can arrive. If we allocate funding intelligently and empathetically, more people can receive excellent care. [1] WHO, 2024. [2] Gallegos, 2023. [3] “The sum of mortality and morbidity is called the “burden of disease” by researchers, and can be measured by a metric called “Disability Adjusted Life Years” (DALYs). DALYs are standardized units to measure lost health. They help compare the burden of different diseases in different countries, populations, and times. Conceptually, one DALY represents one lost year of healthy life – it is the equivalent of losing one year in good health because of either premature death or disease or disability.” (Roser, Ritchie, & Spooner, 2021). [4] Caulfeild, et al., 2013. [5] CDC, 2017. [6] Greenan, n.d. [7] Goldstein, 2000. [8] Scarpina & Tagini, 2017. [9] MoCa Test, 2024. [10] Kwah, L.K., Bappsc, Kwakkel, G., & Veerbeek, J.M. J., 2019. [11] Mittal, S. & Mittal, S., 2025 [12] Mcfarland & Wolpaw, 2017. [13] World Health Organization, 2024. [14] Lee, F., Feldner, H., Hsieh, K., et al., n.d. [15] Scherer, M. & Craddock, G., 2002. [16] IDEO, 2025 [17] InfOT, 2024 [18] Autodesk, 2025 [19] Molteni, F., Gasperini, G., Cannaviello, G., & Guanziroli, E., 2018. [20] Wilkins, K. & Yao, J., 2020. [21] Calderone, L., 2019. [22] U.S. Department of Justice Civil Rights Division, 2025 [23] Office of the Assistant Secretary for Administration & Management, n.d. [24] Tanis, F. & Langfitt, F., 2025 [25] Carter, J. 2025 [26] NIHCM, 2025 [27] Robins, M. 2023 [28] RICOH, 2025 [29] Tierney, A., Gayre, G., & Hoberman, B., et al., 2025 [30] PracticeQ, 2025 Dr. Michelle Johnson specializes in engineering robotics for stroke rehabilitation, and her course has been very impactful for me. The principal elements at work when it comes to physical therapy robots are expertise with anatomy, diagnostics, programming, and fabrication. But at the root of this topic are empathy and optimism: the people who are working in the forefront of this field care deeply about equity and problem-solving, for disabled individuals, the people who care for them and the communities they belong to. They want to meet a human need that is real and important: self-efficacy, through genuine involvement in one’s surroundings. Our in-class lectures began by clarifying the relationship between disability and function, in context. Health-related challenges due to chronic illnesses and disabilities significantly impact individuals’ quality of life (including life expectancy) and societal participation. The World Health Organization reports that noncommunicable diseases (including cardiovascular diseases, cancer, diabetes, and chronic respiratory diseases), now account for 75% of all global deaths.[1] These conditions disproportionately affect low- and middle-income countries, where healthcare infrastructure may be most limited. According to the NCD Letter Letter to National Advisory Council on Minority Health and Health Disparities, many survivors of such diseases in America live with long-term physical and mental well-being impairments, exacerbating social and health disparities, especially where therapy and assistive services are biased or scarce.[2] The correlation between per-capita healthcare spending and “Disability Adjusted Life Years”[3] is well-demonstrated in the following chart (see figure 1). The more we spend, the longer people live. Of course, preventative care and physical therapy contribute to better health and financial outcomes in the long run. Disability is more than a medical condition. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health provides a model that demonstrates an interaction between health conditions, body functions, personal activities, participation in social life, environmental factors, and personal factors.[4] It follows that impairments in body structures (for example, because of a stroke) may lead to activity limitations and participation restrictions, but these can be mitigated through targeted interventions. Pain points are relevant, and must be considered while a person aims to return to “normal.” The goals of rehabilitation are to increase someone’s ability to interact with the real world on their own or with an assistive device by reducing impairments, enhancing capacity, and ultimately improving their lives. If a therapy approach is not effective in these goals, then the plan must be adjusted. Capacity refers to a person’s innate ability to perform a task without support, while performance refers to what they can actually do in real life, often with the aid of therapy or technology. Rehabilitation clinicians play a key role in assessing both, often relying on models of disability to guide decisions. For example, the Timed Up and Go (TUG) test[5], the Box and Blocks test[6], and Grooved Pegboard test[7] each evaluate upper or lower limb function, using speed and various aspects of movement (stability, gait, stride, dexterity, and dropped pegs, respectively). Cognitive assessments like the Stroop Test[8] and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment measure mental performance in terms of either cognitive interference or “short term memory, visuospatial abilities, executive functions, attention, concentration, working memory, language, and orientation to time and place.”[9] These tools generate quantitative data that can be compared against normative populations, aiding diagnosis, therapy planning, and insurance approval for devices. According to Stroke Rehabilitation, the predictions physicians make on their own are not as accurate as the predictions they could make using research evidence (prognostic studies or prediction modeling studies). This may be because studies use or evaluate multivariable prediction models, and must test representative cohorts, standardize the measurement of predictors and outcomes, and conduct external evaluations.[10] Artificial intelligence is working its way into stroke analysis, as well. Rem Azar (a PhD candidate in Dr. Johnson’s lab), is currently using brain imaging to correlate specific dead neural tissue regions to physical and cognitive functioning. Machine learning might help to streamline this process (algorithms can diagnose brian scans and make predictions and treatment recommendations[11]), but a therapist is still necessary to employ best practices. Multifaceted analysis can lead to better plans. Clearly, clinical practice is benefitted by the use of technology. Assistive Technology (AT) includes any tool, device, or service that helps individuals perform tasks they would otherwise find difficult or impossible. These range from low-tech aids like canes to high-tech devices like robotic limbs or even EEG-driven interfaces, which translate brain signals into coded commands[12]. AT can be assistive, adaptive, or rehabilitative. Devices may be load-bearing or weight-bearing, passive or active, wearable or stationary. Their primary aim is to increase the user’s independence and participation across environments (home, work, community).[13] This diversity of devices aligns with the Human-Activity-Assistive Technology (HAAT) model[14], which emphasizes the interaction between user, device, task, and context. Despite the promise of AT, many devices are abandoned because they are not a good fit for the client. To meet this need, the Matching Person and Technology (MPT)[15] framework aims to achieve user-device compatibility. Effective devices must not only work well but also align with user preferences, cognitive abilities, daily routines, and social environments. The steps in this framework are to 1) establish goals and alternative goals, and list intervention and technologies needed, 2) identify satisfaction with past technologies used and interest in different technologies, 3) compare consumer and professional opinions on the technology under consideration, 4) discuss potential issues with the technology that was chosen, 5) formulate strategies and an action plan to mitigate these issues, and 6) commit the plan to writing, which also serves as documentation for funding or other purposes. Appropriate strategies on the front end of AT choice can make all the difference in outcomes. The origin story of AT happens in the lab, and many minds come together to develop products. Design thinking (particularly methods from IDEO)[16] calls for ideation, empathy, and iteration. For instance, in a case study we conducted in class involving a 13-year-old girl with cerebral palsy in rural Ghana, considerations for AT included portability, solar-powered charging, and toy-like appeal for fine motor skill development. Most importantly, our client wanted to communicate more easily. We were encouraged to use the HAAT model[17] to come up with as many ideas as possible, following these rules: In the end, we converged into two groups with two separate designs to carry out and then convince funders with an “elevator pitch.” In real time, we saw the need for practical, user-centered, culturally appropriate, and playful tools that offer therapeutic benefits. It is worth it to mention the methods we used to practice the engineering design process in class. The first way we worked on our wheelchair-compatible devices was to sketch individual ideas and share them (see figure 2, plan by Alyson Iovacchini). Next, Dr. Johnson grouped us based on the commonalities of our visions. We then agreed on a single cohesive plan for each group, and worked together to build triwall cardboard prototypes, using steak knives, x-acto blades, and hot glue. This is one way that her university students build their models; it was low-risk from both a time and materials perspective, and greatly helped to test size compatibility and ease of manipulation. We also explored a hypothetical “What if she needed a better button?” problem. Our case study wanted to play with a toy, but the switch was just too difficult to use. We used Tinkercad[18] (see figure 3) to plan for an interaction between a breadboard, an arduino, and various circuits, an LED light, and a button. At the same time, we built a similar system with physical versions of the aforementioned items, and a bunny toy with a too-small switch (see figure 4, image by Alyson Iovacchini). It was quite a thrilling experience to push the button and be startled by my bunny’s wild sound and movement. I imagine that a child who was once unable to do this independently would feel the same joy at finally making it happen. As the global demand for therapy outpaces available clinical resources, especially in rural or under-resourced areas, robotic rehabilitation emerges as a scalable alternative. Robotics can deliver repetitive, data-driven therapy that promotes neuroplasticity and recovery post-stroke or injury: “they can maximize afferent input from peripheral joints and provide task-specific stimulation to the central nervous system to promote functional recovery.”[19] Robots learn therapists’ and patients’ movement trajectories through kinematics and haptics, and may be trained using machine learning based on therapists’ interventions.[20] Shafagh Keyvanian (another one of Dr. Johnson’s PhD students) explained that they offer both passive (guided motion) and active (resistance training) modes. However, robots still lack the human insight necessary to interpret “intent” or make nuanced decisions, presenting challenges in replicating therapist behavior. Right now, they are limited by human abilities in programming. During our visits to the GRASP Lab at Penn and the Rehabilitation Labs at Penn Medicine, we learned that autonomous systems continue to evolve by analyzing muscle signals through electromyography (a diagnostic test that assesses the health of muscles and the nerve cells that control them), ultrasound, and electroencephalogram (a test that measures and records the electrical activity of the brain). There was a small motion, grip, and pressure sensing setup for early intervention in babies with cerebral palsy. There were “serious games” set up for people to play against their own best score, or each other, and improve their strength, smoothness, and speed while playing. There were 360° video cameras that could notice range of motion, spasticity, and balance much better than the human eye. Robots are already assisting physical therapists in creating complex models of motion and intent. In the words of Len Calderone, since robots can collect so much more accurate data, but lack human touch and nuances, they can only “augment a physical therapist’s job and not replace it.”[21] Despite technical advancements, effective robotic therapy must integrate seamlessly into a user’s life, requiring careful consideration of design, context, and individual differences, and for that we need medical professionals. Even the best-designed technologies can fall short if users cannot access them. Geographic, financial, and institutional barriers, especially in rural settings, often limit access to necessary care and technology. Policies like the Americans with Disabilities Act[22] (ADA) and the Rehabilitation Act of 1973[23] aim to improve access, but implementation gaps remain. Insurance policies, funding availability, and healthcare infrastructure significantly affect the adoption and continued use of AT. Devices that are not covered, or that require expensive customization, may be deemed unusable regardless of their effectiveness. Since context was so important throughout our course, I must mention that at this time, the United States has withdrawn support for most formerly USAID-funded programs.[24] People with both communicable and noncommunicable diseases all over the world have depended on these clinics and the resources they provided for their livelihood. The Priority Assistive Products List explains that even before this new status quo, “People from the poorer sectors of society frequently rely on donations or charitable services, which often focus on provision of large quantities of substandard or used products.” Now, the global nongovernmental organizations that did this good work are even more overburdened, and are turning people away. We are also now waiting to see if the new federal budget will cut Medicare funding.[25] Proponents of this budget claim that states will be responsible for coverage. Healthcare workforce shortages are dangerously low, particularly in rural areas (where they also lack internet access and therefore cannot use telehealth services), and as our population ages, this issue will only grow in urgency.[26] Given that we seem to be under emergency, it may seem that the idea of robotics in physical therapy is impractical or fantastical. Quite the opposite: technology can solve our human services problem and be more cost-effective in the long run. Drones can deliver medicine to hard-to-reach places.[27] 3-D printers can produce medical devices and personalized AT.[28] Therapeutic robots can support diagnostics and “hands-on” practices. AI scribes can convert physician’s notes into database entries quickly and correctly.[29] Software can inventory medical supplies and automatically re-order them when needed.[30] Better internet access can bridge the gap between no access and virtual access until help can arrive. If we allocate funding intelligently and empathetically, more people can receive excellent care. [1] WHO, 2024. [2] Gallegos, 2023. [3] “The sum of mortality and morbidity is called the “burden of disease” by researchers, and can be measured by a metric called “Disability Adjusted Life Years” (DALYs). DALYs are standardized units to measure lost health. They help compare the burden of different diseases in different countries, populations, and times. Conceptually, one DALY represents one lost year of healthy life – it is the equivalent of losing one year in good health because of either premature death or disease or disability.” (Roser, Ritchie, & Spooner, 2021). [4] Caulfeild, et al., 2013. [5] CDC, 2017. [6] Greenan, n.d. [7] Goldstein, 2000. [8] Scarpina & Tagini, 2017. [9] MoCa Test, 2024. [10] Kwah, L.K., Bappsc, Kwakkel, G., & Veerbeek, J.M. J., 2019. [11] Mittal, S. & Mittal, S., 2025 [12] Mcfarland & Wolpaw, 2017. [13] World Health Organization, 2024. [14] Lee, F., Feldner, H., Hsieh, K., et al., n.d. [15] Scherer, M. & Craddock, G., 2002. [16] IDEO, 2025 [17] InfOT, 2024 [18] Autodesk, 2025 [19] Molteni, F., Gasperini, G., Cannaviello, G., & Guanziroli, E., 2018. [20] Wilkins, K. & Yao, J., 2020. [21] Calderone, L., 2019. [22] U.S. Department of Justice Civil Rights Division, 2025 [23] Office of the Assistant Secretary for Administration & Management, n.d. [24] Tanis, F. & Langfitt, F., 2025 [25] Carter, J. 2025 [26] NIHCM, 2025 [27] Robins, M. 2023 [28] RICOH, 2025 [29] Tierney, A., Gayre, G., & Hoberman, B., et al., 2025 [30] PracticeQ, 2025

We also explored a hypothetical “What if she needed a better button?” problem. Our case study wanted to play with a toy, but the switch was just too difficult to use. We used Tinkercad[18] (see figure 3) to plan for an interaction between a breadboard, an arduino, and various circuits, an LED light, and a button. At the same time, we built a similar system with physical versions of the aforementioned items, and a bunny toy with a too-small switch (see figure 4, image by Alyson Iovacchini). It was quite a thrilling experience to push the button and be startled by my bunny’s wild sound and movement. I imagine that a child who was once unable to do this independently would feel the same joy at finally making it happen.

We also explored a hypothetical “What if she needed a better button?” problem. Our case study wanted to play with a toy, but the switch was just too difficult to use. We used Tinkercad[18] (see figure 3) to plan for an interaction between a breadboard, an arduino, and various circuits, an LED light, and a button. At the same time, we built a similar system with physical versions of the aforementioned items, and a bunny toy with a too-small switch (see figure 4, image by Alyson Iovacchini). It was quite a thrilling experience to push the button and be startled by my bunny’s wild sound and movement. I imagine that a child who was once unable to do this independently would feel the same joy at finally making it happen.

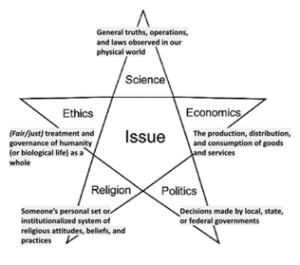

A typical socio-scientific issue[1] (SSI) unit starts with a question that engenders debate. For this unit, our titular question is Should We Publicly Insure Robotic Physical Therapy for Disabled Individuals? We focus our inquiry in figuring out the issue, as well as the science around it. There is never one simple answer to the ethical question, and in this case, there are compelling physics and biology topics. Medicaid waiver waitlist leaves Montana’s disabled facing tough choices[2] starts the class and serves as an anchoring phenomenon, which we see as a relevant and current connection. Notice/Wonder charts are a simple protocol for new information, for collecting observations and questions and then sharing them. I then introduce the SSI question, and we’ll create an opinion line, in which students will name and explain their position on the issue, and physically place it (via posit-it note) on a line on the wall, which will be followed by a debate, in which students elucidate their opinions while following classroom norms.[3] It is important to set an expectation for sharing bravely, thinking critically, and listening to understand. After this, we share our prior knowledge on assistive technology and disabilities. It’s important to tone-check here: disability is not bad, and about 13 billion people (16% of all people) are significantly disabled, so it’s common.[4] This is a good opportunity to see what students already know and feel. Students will likely think that assistive technology is the best way to support disabled persons’ full participation in society, though they may not have this vocabulary yet. They’ll talk about wheelchairs and prosthetics, but they probably won’t think about robotics and physical therapy. Before going further, they get a few bites of information (an occupational therapy assessment[5] video, Stroke Therapy Training[6] video, and Medicare Coverage[7] reading), to build some knowledge about what therapies can look like, and what insurance is, using the Notice/Wonder method again. We will then use a “star” chart to explore the scientific, political, economic, religious, and ethical aspects of the issue; this is a way of eliciting prior knowledge and making relevant cross-curricular connections. Students are likely to know very little at this time. I have found that after teaching for years in this way, they get better at inferencing possible viewpoints instead of just looking things up, finding an answer, and thinking they’re finished. If students do this in groups, it’s a form of productive talk. It also gives the teacher time to walk around the room and listen or ask questions. They see that science touches all aspects of life and does not exist in a vacuum, and is often not neutral. Next, we’ll start with individual initial models[8], which elaborate on the scientific point of the star, and begin with a question: How does assistive technology affect disabled individuals? I always have the rules for models posted in the room, seen in the Knowledge section of the standards-based project rubric (see Appendix I). Students are likely to understand that furniture, architecture, and business infrastructure may or may not be designed with different abilities in mind. If I have time, I allow students to share and compare models[9], and even create must-have lists. As the teacher, I’m sure to have an idea of the goals of this model: Disabled individuals have specific and measurable abilities, just like anyone else, and assistive technology helps with that. I also know that there are going to be a lot of unanswered questions when we get to modeling, and it’s fine to ask those questions and record what the students agree upon, even when it’s wrong, or put question marks next to statements we’re not sure about. Then, as a class, we create a consensus model[10] (which is open to revision) that shows what we know and agree upon so far. The Progress Tracker is a single document that students use throughout the unit. While it is graded in the Process section of the project rubric, it is more qualitative than quantitative. Students should be using it to make connections between lessons, and they can also use it as a reference when doing their argumentative writing later on. As the teacher, I look to see that students were able to use three dimensions of science[11]: I usually remind them of the science and engineering practices (SEPs) we engaged in, and I look for which disciplinary core ideas (DCIs) or cross-cutting concepts (CCCs) they learned. I place the SEPs and CCCs in a prominent place in the room at the beginning of the year, so they know where to find them. Students add to it at the close of most or all lessons. After modeling, we are a little clearer on what we do and don’t know, so we begin to explore one of those ideas: AT items and how they work. For lesson two, student groups choose at least one item from a list, make it and use it, assess their own limitations, and share their work in a gallery walk.[12] I have found that if students can learn by doing and presenting, there is higher engagement and better retention of content. An alternative is to have several assistive products available for students to use; it cuts down on time and mess and is still fun and informative. To pique students’ interest with a variety of AT they haven’t seen yet, they can extend their learning by getting to know Barbara (a disabled teen) and others like her.[13] Lesson three is an open-ended investigation (see appendices 2-7). I use a one-size-fits-all handout[14] for these, so students are very familiar with the format and can spend their brainpower thinking about the content. If they prefer to use a worksheet and follow directions, they also have that option. They are broken into mixed ability groups for the 1) Forces and Motion simulation[15] and worksheet[16], 2) the Circuit Construction simulation[17] and worksheet[18], 3) the the Sound Waves[19] and Waves on a String[20] simulations, A/D Conversion video[21] and worksheet[22], 4) the Balancing Act simulation[23] and worksheet[24], and 5) the Faraday’s Electromagnetic Lab[25] simulation and worksheet[26]. After they do their investigations, they make anchor charts and present them to the class. It’s a best practice to have an anchor chart example available, as well as sentence starters, for EL and SPED student support. Students learn better by doing, reading, writing, speaking, and listening, and they do all of these things, as well as critical thinking, while doing investigations. At this point, students should have a better foundation for thinking about which physical processes might go into AT or robotics, so in lesson four, we formulate a Driving Question Board (DQB)[27] to collect and categorize any questions we have. We also talk about which sorts of investigations and research may lead us to answers. It is important for students to have time to name these big questions, but they should make sure that they are ones that need more than Google for an answer. Though this is not detailed in the classroom activities section, at this juncture, we may want to make time immediately after the DQB to introduce an essential question of this unit: “How would we assess this person’s abilities in order to better support them? What do we need to know and do?” Students are likely to think that a doctor does this work, but they would not have a clear idea of how. So we’ll set up a Notice/Wonder chart and look at two key sources: World Health Organisation Disability Assessment Schedule – Children and Youth version (WHODAS-Child)[28] and 5:36-8:00 of Dr. Michelle Johnson’s TED talk.[29] When we discuss our notes, we’ll see that both low- and high-tech solutions can help people with the activities of daily living. Thus, we arrive at another essential question: “How do we process someone’s skills, limitations, and motivation in order to come up with a plan?” If you don’t have time for these activities, you may want to assign them as homework or DO NOWs in the beginning of class. Once these introductory routines are accomplished, we can start facilitated classwork. First, we need to define disability. According to the World Health Organization, “Disability results from the interaction between individuals with a health condition (and) personal and environmental factors including negative attitudes, inaccessible transportation and public buildings, and limited social support.”[30] Students may by now understand that a substantial part of society might not “fit in” as they do, and that anyone can be born disabled, or become disabled, at any time. So the next and largest step in our inquiry process is to explore what these health conditions are, how we can evaluate peoples’ interactions with their surroundings, and how we can then use best practices to adapt our overall approaches or reflexively accommodate these individuals. This naturally unfolds with the first step in our project-based approach[31], which is using engineering design process[32] to create solutions for real case studies[33]: Students will become familiar with the HAAT model[34] (see figure 5) in order to make a claim by finishing the sentence “___ will need ___ so they can ____.” Since their claim must be supported by evidence, and they are new to this topic, they will leave it as an incomplete prompt while mining their two-paragraph blurbs for crucial details and filling out a simple chart. Then they’ll do individual sketches of the products they proposed. The collaborative HAAT activity will segue into lesson five, for some structured research on their individuals’ disability or ways to evaluate it (for example, the Gross Motor Function Measure[35]). It’s important to provide graphic organizers while they do this work, so they have an easy reference point while defining the problem[36] (see appendix 8). After researching, they will reiterate their product sketches together, and build their first prototype. They can do these steps manually, or digitally with Tinkercad (a web app for 3D design, electronics, and coding) and 3D printers if available. The testimony of Jane Velkovski[37] is a deliberately-placed reminder of our purpose in lesson six, the midpoint of the unit. Before getting into the details of prototype testing, we should float the concept of distributive justice, which “advocates for a redistribution of resources to account for… inequity. It is based on principles “designed to guide the allocation of the benefits and burdens of economic activity.””.[38] It is a reminder that product design can be a great equalizer, and cost and availability are worthwhile measures to include this population in more just ways. When students test, collect data, reflect, rebuild, test, collect data, and reflect again, they are engaging in 21st-century skills and life skills, which prepare them for an ever-changing world. As Ahmet Erol explains, “Engineering education… contributes to children’s problem-solving skills with failure analysis and continual improvement habits of mind.” [39] Teachers can help students be successful in this by encouraging students to rethink the problem, be patient and determined, and communicate and collaborate with others. This could be facilitated easily if students evaluated the effectiveness of each other’s solutions with a backwards HAAT model: Does this AT fit in the context that an activity occurs in for this particular human, with their unique motor and cognitive skills? Or might this AT work universally, for a variety of people? This piece of our project would follow a standard engineering design rubric, as well as a modeling rubric, as detailed in the Design and Knowledge sections of the project rubric. Evaluating their own and others’ products, and reiterating their designs, would help students to exceed expectations. When the class has a discussion to revise the consensus model,[40] be sure to prompt students towards fully explaining their claims, so an accurate and complete model is the result. At the start of lesson seven, students do a navigation routine to evaluate where they’ve been on the SSI journey (which questions on the DQB have been answered), and where we still need to go to better answer our unit question. Clearly, there isn’t time to engineer robots. But there is time to learn more about healthcare funding and its effects on the disabled population. To start with a humanistic approach, we watch People with disabilities discuss impact of Medicaid cuts[41] and think about how many Americans are genuinely worried about their future. What is it that they need to thrive? This depends on whether conditions are short- or long-term, and students can differentiate between these via a low-pressure word sort. Students have both choice and voice when they explore topics in the CDC’s Disability and Health Index[42], and share what was impactful for them. There are five resources I provide during lesson eight for students’ research into healthcare: A proposal for universal basic coverage[43], Best Disability Insurance Companies Of 2025[44], The best disability insurance companies of 2025[45], Coverage options for people with disabilities[46], and Years lived with disease or disability vs. GDP per capita, 2021[47]. It may be interesting for them to see the differences between the “best” lists, and try to figure out why. Students do a What I See/What it Means strategy, but they think about what the readings mean in both the short and long term for individuals, as well as what it means for society. When they return to their design groups to discuss what a loss of coverage would mean for their client, they are faced with the reality that products are useless if people are unable to access them. The penultimate graded assignment in this project is a persuasive writing assignment that requires students to explain whether we should publicly insure robotic physical therapy for disabled individuals. For lesson nine, they can use any and all of what they’ve learned so far, but they are also required to provide visual data and the voices of stakeholders. For example, physical therapists may worry about losing their jobs, while patients just want the best and most accessible care possible. Not only does a Claim, Finally, students make their action projects. They can choose between collecting accessibility data via Walk Audits[50] in their neighborhoods, making recommendations for improvement, and sharing their work, or creating an informational PSA about the ADA and sharing it. Regardless of their choice, this is an advocacy-type project, which aims to achieve justice by bringing visibility to the cause of disabled people’s rights, and convincing the public that there are things we can do to show we care. In this way, students demonstrate citizenship. Because this component of the Presentation score is so creative, they can style it and make it their own. They finish the unit and their Presentation grade with class debate. They are able to use their CERR for reminders, but this piece of the unit is really about discourse. Students are encouraged to start statements with phrases like “I (dis)agree with ___ because their idea of ___, but …” They can question each other. Providing them with Self-evaluation: Engaging In Classroom Discussion[51] may help students to hold themselves and each other accountable for good-faith contributions to the scientific community. Following debate, they reflect on their own learning by taking their opinion from the line, taking their question from the board, and journaling about whether their ideas have changed since the beginning and why, or whether they have better reasons for feeling as they did. They think about the answers to their questions, and whether some of them could be answered with further research, or never answered simply. By teaching inquiry-based, project-based, SSI units, I have had to put a lot of thought into what I teach and how I teach it. It hasn’t been easy, and while I have felt supported at SLA-MS in this journey, not everyone is so lucky. In the words of Sweetland and Towns, “Administrators, parents, or even students may not recognize the hard work that goes into planning and implementing an inquiry-based approach—in fact, it may seem that teachers “aren’t doing anything” as students struggle to formulate questions and seek out answers.”[52] As I think back on years of teacher institutes, long nights giving feedback, grading and re-grading resubmissions, I think that learning isn’t supposed to be simple, and neither is teaching. Yes, middle school students can wonder about disability, insurance, robotics, and healthcare. They should be thinking about the world around them, even if it doesn’t seem to affect them directly. I believe that doing this “messy” SSI work is an investment in the future. If we really want our students to be the future engineers, researchers, ethicists, or anything of tomorrow, we need to give them reasons to think about it today. [1] Zeidler, D.L., & Nichols, B.H., 2009 [2] NBC Montana, 2023 [3] OpenSciEd, 2019 [4] WHO, 2025 [5] St. David’s Center, 2017 [6] Helen Hayes Hospital, 2016 [7] Center for Medicare Advocacy, 2025 [8] Ambitious Science Teaching, 2015 [9] Instructional Leadership For Science Practices, n.d. [10] OpenSciEd, 2025 [11] Duncan, R. & Cavera, V., 2015 [12] Alber, R., 2016 [13] Blythedale Children’s Hospital, 2017 [14] OpenSciEd, n.d. [15] PhET Interactive Simulations, n.d. [16] Borenstein, S. 2013 [17] PhET Interactive Simulations, n.d. [18] Jefferson County Middle School Workshop, 2017 [19] PhET Interactive Simulations, n.d. [20] PhET Interactive Simulations, n.d. [21] Mixed Signals, 2023 [22] Podolefksy, N., 2024 [23] PhET Interactive Simulations, n.d. [24] Michalski, K., 2021 [25] PhET Interactive Simulations, n.d. [26] Herman, J., n.d. [27] OpenSciEd., n.d. [28] NovoPsych, n.d. [29] Johnson, M., 2017 [30] WHO, 2025 [31] BU Center for Teaching and Learning, n.d. [32] TeachEngineering.org, n.d. [33] Connecticut State’s Department of Education, 2025 [34] Simpson, C, 2015 [35] Cerebral Palsy Alliance, n.d. [36] TeachEngineering.org, n.d. [37] Velkovski, J., 2022 [38] Cook, A., 2015 [39] Erol, A., 2024. [40] Michaels, S., & Moon, J., 2016 [41] PBS News Hour, 2025 [42] CDC, 2025 [43] Einav, L. & Finkelstein, A., 2023 [44] Masterson, L., 2025 [45] Knueven, L., 2025 [46] HealthCare.gov, n.d. [47] Our World in Data, 2021 [48] Achieve, n.d. [49] Meriam Library, 2010 [50] AARP, 2022 [51] OpenSciEd, 2022 [52] Sweetland, J. & Towns, R., 2008

Evidence, Reasoning, Rebuttal response (CERR) pass the NGSS Science Task Prescreen[48]; it also requires students to justify their ideas. In Science, opinions are backed up by facts and a deep understanding of processes. They must evaluate their sources to make sure that they’re trustworthy.[49] They have to consider their own biases, and weigh their values rationally. I have found that students who take their CERRs seriously throughout the years improve dramatically in their writing skills, and I believe it is because of the inherent emphasis on personal beliefs through truth. This is evaluated with the Application section of the rubric.

Students will be able to independently use their learning to: Additional standards met during instruction would vary based on the investigations students chose to do, but there are clear transdisciplinary connections to Social Studies, English Language Arts, and Technology. Transfer Task(s) Other Evidence What might this unit follow and lead to? This unit would be best placed between studies on contact forces and motion, and studies in electromagnetism. It would also be an effective segue between simple machines and energy waves (electromagnetism, or digital and analog communication). The science of engineering design and robotics uses an understanding of kinematics and applied technology, so it would fit nicely between any related topics. Activities and Notes Lesson 1 Have students set up a Notice/Wonder chart to guide their work. Watch Medicaid waiver waitlist leaves Montana’s disabled facing tough choices. Share what stood out. Now, it’s time to put your opinion on the line. Here’s the question: Should We Publicly Insure Robotic Physical Therapy for Disabled Individuals? Remind students that they can use information from the video to explore their own opinions. Have students write their name and the issues they are most concerned about on a sticky note and place it somewhere from “definitely” to “never.” Then ask students along the continuum to explain their answers and reasoning. Remind students that there is no “right” answer here, but they should make a choice with conviction. You may want to go over some classroom norms if students need a reminder, before the unit progresses much further. Discuss and share: What do you all know about disabilities? How do we use assistive technology in our everyday life? Now, let’s look at some related phenomena. Return to your Notice/Wonder chart, and use it to collect notes on the videos and reading. Watch Occupational Therapy Assessment: A Case Study and Stroke Therapy using Locomotor Training at Helen Hayes Hospital. Read Medicare Coverage for People with Disabilities. Explain to students that we will be exploring this content deeply in the upcoming unit. We’ll start with doing an initial model about parts and their interactions. Try to explain energy’s role! Individually, you will draw/write models to address these questions: How does assistive technology affect disabled individuals? These models are made to show how a process could work, and do not yet need to be correct. Give students time to work. Then, we will share our ideas to create a class consensus model. Begin a Progress Tracker in the back of your science notebook, and add an entry at the close of class. You’ll need 3 columns, and you will add to these when prompted to do so throughout the unit. Lesson 2 We started to talk about assistive technology. You did your initial models to try to explain how some AT may work, and how it helps disabled individuals. But how could we find out more about the structures and functions in AT? Students will likely suggest that they research assistive technology. Approve that idea as the next course of action, but frame it as an exploration WITHOUT any tech support. Ok, so each table should start by exploring a low-tech AT item. Here is a list that can help you choose: For writing and fine motor skills: Pencil grips, adapted pencils, adapted scissors, slant boards, and textured paper. For visual impairments: Magnifying glasses, large print books, highlighters, and adapted rulers. For communication: Communication boards (picture or word-based), alphabet boards, and simple switches. For mobility and daily living: Canes, walkers, grab bars, adapted eating utensils, and button hooks. For organization and support: Visual schedules, checklists, and color-coded materials. Try to make and/or use at least one of these items, write down your observations about the experience, and try to illustrate the structures and functions of your chosen AT WITHOUT looking anything up. Give students time to work. Are there any limitations to your planning/execution/explanations? Discuss in your groups. Then, interact with each other’s observations/illustrations via a “project share”-type gallery walk. Write impactful student ideas on the board, and use these to revise the class’ consensus model. Each student should add an entry to their Progress Tracker. If you want to extend your learning this evening, watch as much of Assistive Technology – Unlocking the Future as you have time for. Lesson 3 We discussed the structures and functions of some AT yesterday, and while we identified how some objects can make certain aspects of life easier, we didn’t really explain enough about how they really work. For example, manual and electric wheelchairs operate differently, but does everyone know how? Can you explain how speech-to-text actually happens when you use it in a google doc? This relates to the “science” point of our Star Charts (point to the Star Chart), and as you can see, we still have a lot to figure out. We’re going to help each other with this. You’ll each be responsible for doing your part. Each of you will use the linked simulation materials AND your own research to investigate phenomena, and explain how energy and matter do some sort of work (make something move). Divide the class into 8 groups, so they can each create anchor charts. You may want to provide an anchor chart example, including sentence starters, to support SPED and ELL students. Here are your group assignments: What each group will do: Give students time to work. Then, hold presentations. After every group presents their work to the whole class, list key take-aways for each of the 4 topics on the board, and discuss how these understandings help to explain the phenomena of some AT. Be sure to keep posters displayed in a prominent location throughout unit work. Then, revise the class consensus model. Each student should add an entry to their Progress Tracker. Lesson 4 You did an excellent job with your investigation presentations yesterday. I’m wondering if there are some burning questions that we can try to resolve moving forward, particularly any that are aligned to our unit’s question. We’re going to share this by creating a Driving Question Board and making sure our questions are organized by topic. Procedure: Students call on each other, and each must explain how their question is related to the previous question. Afterwards, agree upon topics to group questions by, and then do so. Likely ideas will relate to the science behind assistive technology, disability, insurance, and robotic physical therapy. Ask students how we might start to investigate and find out more, and write any ideas that are actually testable/researchable in a prominent place. If it doesn’t come up organically, lead the class toward looking at real cases of disability and assistive technology. Engineering and design is a logical way to start working through these questions. Provide all students with copies of the Design and Knowledge sections of the project rubric, as upcoming work will be graded, and they should know what is expected of them. In case you’re not familiar, let’s view the process. We are going to design some assistive technology for people with specific disabilities, and we’ll be using something called a HAAT model to identify particular needs and constraints. First, let’s watch The Human Activity Assistive Technology Model for some guidance. Students can also look up a general definition of disability at this time, and share. After we look at some case studies, we’ll choose one or a few specific needs for our clients. Here are your assignments. Divide students into about 8 mixed-abilities-groups of 3-4 children, and give each group a printout of one of the following blurbs from Connecticut State’s Department of Education: I know that these case studies are from Connecticut, but please imagine that all of these kids go to school in Philadelphia. Now, work together to fill out this HAAT organizer to complete a claim for your groups’ client by finishing the sentence “___ will need ___ so they can ____.” Give students time to work. Before doing any research, each individual group member must develop a quick sketch of what you think this AT product might be like, including structures and functions. Feel free to refer to our anchor charts to support your thinking. Give students time to work. Add another entry to your Progress Tracker. Lesson 5 Have the engineering design loop on the board for students at the start of class. So, where are we in this process? Where do we need to go next, and why? Yes, we need to do some research on our case studies’ specific disabilities, before developing any more possible solutions. In your groups, fill out this chart in your own words, and cite your sources. You may use any information from federal government agencies, medical schools/clinics, or large professional or nonprofit organizations. Give students time to work. Now that you know more, it’s time to make a plan. Use TeachEngineering’s Defining the Problem Worksheet to consider the necessary factors, one step at a time. You’ll need to agree on all of this. So for parts C and D, pull out your initial AT sketches, and compare them. Refer to your group’s HAAT model and today’s research. Which elements seem to lead in the direction of a product that will work for your client? To clarify this further, create another sketch (either by hand or by Tinkercad if you are able to independently pursue a robotic application), this time as a group. You will likely revise your “need” claim, as well as any plans you came up with yesterday. Give students time to work. The next step in our engineering design loop is to build a prototype! You may use any physical materials available to create a 3D model. Give students time to work. Add an entry to your Progress Tracker. Lesson 6 Play Jane Velkovski: The life-changing power of assistive technologies | TED from 2:48-5:42. Why is product development important? How were assistive technologies like the manual and power wheelchairs developed and refined? Listen to all ideas, but highlight those that fit the engineering design process. Once again, display the engineering design loop on the board. What’s next? Effectiveness studies! Test your prototypes, collect any data/measurements/feedback you can, and analyze the results. Refer to part G of the Defining the Problem Worksheet your group made to standardize your trials, and team up with another group to test each other’s designs. Give students time for at least 3 trials per product. Maybe you’ll want to use a chart like this to keep trials consistent from tester to tester: PASS OR FAIL only Once this is finished, analyze the results. Give students time to work. Once again, display the engineering design loop on the board. What’s next? Improve your AT! Re-iterate your 2D and 3D designs. Give students time to work. Then test and collect data again with a different partner group. Give students time for at least 3 trials per product. After 6 trials have been done altogether, reflect on the overall results in writing, below your data sets. If you could do this again, what changes would you make? Remember, you will get two grades for this work, and you can check your performance by using the Design and Knowledge portions of the rubric. Give students time to work. Then collect all data sets, all 2D designs, and all 3D designs for grading and feedback. Let’s do one last amendment to our class’ consensus model of AT. Take student suggestions and revise the model. Add an entry to your Progress Tracker. Lesson 7 You did an excellent job of designing AT. Let’s revisit our Driving Question Board topics, and see if we figured any of them out. Discuss, and surely reflect that certain aspects of AT (those requiring circuits, digital elements, or electromagnetism) are out of our range for experimentation, but we have some very general ideas about how they work. We also see by now that robotics are an upgrade from manual AT in quite a few cases, as the individuals’ dependence on other people is decreased, and they gain independent functioning this way. What we do have the time and materials to look into are the ethical, political, and economic points (point to the STAR chart for reference) of this unit. So let’s get into that. Set up a Notice/Wonder chart in your notebooks. Watch People with disabilities discuss impact of Medicaid cuts. What did you see or learn from this video? What do you wonder? Can you differentiate between short-term and long-term care for people with disabilities? What might that mean? In your groups, do a sorting exercise with the following disabilities, placing them into short- and long-term care. Give students time to work. Here are some suggested topics and an answer key, if you need ideas: Postpartum depression Severe Stress/Anxiety Heart attack Migraine Complications from a surgery or medication Recovery from medical procedure Blindness or vision loss Stroke Traumatic brain injury Neurological disorders Epilepsy ALS Deafness or hearing loss With partners, explore the CDC: Disability and Health site. You may choose your own adventure here: Fill out the note-catcher below, adding rows as necessary: Give students time to work. Share out what was most impactful for you, or what you are still wondering. If someone else says something interesting, write that down! Now, add another entry to your Progress Tracker. Lesson 8 You discussed the ethics of disability care yesterday. But we are still unclear about economic and political details for this topic. Today is the day for that. As a class, we are going to read Designing US health insurance from scratch: A proposal for universal basic coverage. Discuss the main points of the one-page version of this proposal. What would you need to know for this proposal to make more sense? Use some informational text reading strategies to select some general ideas that require evidence. Do you think that this insurance plan, or any plan, would cover assistive technology or physical therapy for disabled individuals? What do existing plans offer? How would you find out more? It’s another research day. We’re going to use the same style of note-catcher as last time, but this time, we’re going to look at insurance. You might want to check these resources before doing your own research: Forbes: Best Disability Insurance Companies Of 2025 CNBC: The best disability insurance companies of 2025 Healthcare.gov: Coverage options for people with disabilities Years lived with disease or disability vs. GDP per capita, 2021 Give students time to work. Share out what was most impactful for you, or what you are still wondering. If someone else says something interesting, write that down! Return to your Engineering Design groups (who you worked with on your case study AT). What would great insurance coverage mean for your client? What would a loss of coverage mean? Talk specifics. Allow for small group discussion, then do a whole-class discussion. Now, add another entry to your Progress Tracker. Lesson 9 Your next graded project component is to write a CERR-style argument. See the Application portion of your rubric for details, specifically the academic standards you should demonstrate in your writing. Give students time to work. Then collect essays for feedback and grading. Lesson 10 Group discussion: What do we think we can do to impact the problem of inequity in disability care and insurance, while also ensuring community access for all? Discuss. Here are two Advocacy Action ideas: Walk Audits! ADA Compliance PSAs! Refer to the Presentation portion of your rubric for standards and scoring details. Each option is elaborated below. Walk Audit Choice Directions: In your action group, discuss and record answers to these prompts to plan for your Walk Audit. Carry out your plan! Complete your project and turn in an ArcGIS or Google map that features your audit items AND an embedded video that provides a sense of place. Present your project to the class or a wider community according to the Presentation rubric. ADA Compliance PSA Directions: Create posters/pamphlets/videos (Public Service Announcements) to raise community-wide awareness about the Americans with Disabilities Act. These PSAs should include: Present your PSA to the class and the wider community according to the Presentation rubric. Allow students to work and then present their audits and PSAs. After presentations: Add an Entry to your Progress Tracker. Lesson 11 Finally, it’s time to apply what you know in debate. Should we publicly insure robotic physical therapy for disabled individuals? Have you changed your opinion from what it was at the start of this unit? What do you think now? Discuss this as a class in a circular seating arrangement. Have your debate. Revisit the Class Norms beforehand if needed. Add an entry to your Progress Tracker Revisit the Driving Question Board and see what has been answered, and which questions we still have. Pull your own opinions and questions from the board and place them in your notebook. Be sure to write down how you’ve changed your thinking since the start of this unit. You may use this information while reviewing your Progress Tracker, which will be graded with the Process portion of your rubric. Collect Progress Trackers.

Share out: What are some things that caught your attention about this assessment and therapy? What about the insurance coverage? What do you wonder about them? Students may comment on different abilities and the efficacy of therapies. Then pose the questions: “How does physical therapy work? Why have robots ? What are the costs and benefits of using them in physical therapy?” As a class, we’ll use a STAR chart (see above) to start organizing our thoughts on this. Complete the STAR chart as a class.

Share out: What are some things that caught your attention about this assessment and therapy? What about the insurance coverage? What do you wonder about them? Students may comment on different abilities and the efficacy of therapies. Then pose the questions: “How does physical therapy work? Why have robots ? What are the costs and benefits of using them in physical therapy?” As a class, we’ll use a STAR chart (see above) to start organizing our thoughts on this. Complete the STAR chart as a class.

What we were trying to figure out

What we did

What we noticed and learned (and how it relates to robots in physical therapy)

1 and 2

Newton’s laws (simulation for the First Law) You may use these prompts and notecatcher for the investigation.

3

Circuits You may use these prompts and notecatcher for the investigation.

4

Sound waves and waves on a string, as well as A/D Conversion, Sample Rate & Bit Depth for audio explained, ADVANCED. You may use these prompts and notecatcher for the investigation.

5 and 6

Simple machines- lever You may use these prompts and notecatcher for the investigation.

7 and 8

Electromagnetism You may use these prompts and notecatcher for the investigation.

Human (describe the person in your case study, one characteristic at a time)

Activity (what they need assistive technology to do)

Context (where they will use the assistive technology)

Requirements (for the assistive technology that is needed; these are also design constraints)

Name of client’s condition

Symptoms and impairments (how physical functions are affected)

Treatments (surgeries, medications)

Accessibility needs

Current assistive technology available

Human assisted physical therapies available

Data parameters:

Description:

Method of AT use:

Test subject name:

Test subject environment:

Measured outcomes (including units if possible):

Tester’s evaluation of materials:

Tester’s evaluation of effectiveness of product (did it solve the problem and meet the need):

Short Term

Long Term

Unexpected injury

Musculoskeletal disorders

What I read (specific quote or paraphrase, cite site)

What it means for the short-term health and needs of disabled individuals

What it means for the long-term health and needs of disabled individuals

What it means for the family, community, and larger society

What I read (specific quote or paraphrase, cite site)

What it means for the short-term health and needs of disabled individuals

What it means for the long-term health and needs of disabled individuals

What it means for the family, community, and larger society