This unit, Identity and Ideology: Using Poetry to Explore Who You Are and What You Believe, is designed to use poetry as a medium to engage students in thoughtful, critical conversations about text. It focuses on close reading, structured and scaffolded group discussions, and student-created questions. The unit was created for middle school, but can be adapted to meet the needs of a range of grade levels. The poetry we explore in this unit is all by African American poets, but the poems can be tailored to fit the interests of your students. The goal of this unit is to move students toward rich student-driven conversations about text. This unit can serve as a foundational unit to set norms and expectations for discussion for the school year.

In my seventh and eighth grade English Language Arts classes, my students are eager to contribute, but very uncomfortable with discussion and the vulnerability that comes with it. In this unit, I use poetry as a medium to establish norms and expectations for discussion and questioning in the classroom, as well as creating a playground for living in the uncomfortable space of having more questions than answers. It comes up frequently in conversations with other teachers that students lack a sense of curiosity required of critical thinking and a lifelong pursuit of learning. While I broadly understand the complaint, I think that all of my students have an intense curiosity, but perhaps are not often encouraged or equipped to identify, explore, or explain their questions and ideas. It feels like an example of classrooms becoming more focused on what (content) as opposed to how (process). As a middle school English Language Arts teacher, I am acutely aware of the standardized testing pressures and challenges of the rigor dictated in the Common Core standards. In a classroom where students represent an incredibly broad range of reading levels, interests, and prior learning, it can feel daunting to push students into the meaningful critical thinking and authentic experiences that will result in deeper engagement. I find that I spent a good deal of time toward “un-teaching” the habits that students have grown accustomed to in a teacher-centered classroom. My students often look to me for answers and see learning as binary. The primary goal of the unit will be to work on questioning with students, and guide them toward seeing the learning value in conversation and questions with each other. This first phase will address how students can ask questions of poetry (modeling multiple meanings of words, placement, feelings, etc.) and I will largely model and reinforce with small group practice. The second phase will provide students with opportunities to use poems we’ve studied in class as inspiration to create their own pieces. This unit seeks to address these problems by using poetry to engage students in constructive conversation and meaning making to give students ample opportunities to become active participants in their own learning. Critical to this work is creating an atmosphere of trust in which students will share and participate in the collaborative learning process. In my seminar Modern and Contemporary U.S. Poetry (or “ModPo”), we read and discussed a wide variety of types of poems. Each week was organized with “like” poems (the New York School one week, the Beats another week, for example). We, as students, were told a few specific poems that we would discuss in the next class. As we sat around a large conference table, at least in the first few sessions, each student was given a specific word or phrase to unpack. This “unpacking” process consisted of exploring and explaining what the word may mean or contribute to the poem. Beyond connotation, denotation, or etymology, one might note things like the word’s physical position in the poem, or capitalization. While “unpacking” the word, the seminar leader or classmates may ask questions to extend or explore ideas. With little variation, most of our seminar classes followed this general format. The biggest change being that we, the students, became more comfortable, confident, and engage in and drive the process. The most striking part of the ModPo Seminar experience was how truly democratic the process was. Poetry was a great equalizer, and when distilled to words and phrases, no one student emerged as the one with all the answers. In our group, some of us were English teachers, some were not; a few were avid poetry readers or writers, many were not; some had many years of teaching experience, others did not. Still, each seminar session, our conference table strewn with poems created a level playing field for all of us to engage in dialogue with each other without any pretense. Creating a similar classroom environment has always been my goal as a teacher, but ModPo allowed me to participate in the model as a student. The challenge (and opportunity) that the ModPo seminar presented to me was how to channel a process that is so refreshingly open and unstructured into my classroom. What elements from the ModPo seminar can still convey the collaborative nature of our discussions in a classroom of thirty-eight eighth graders in a productive and meaningful way? While this was a seminar on poetry, typical teaching points of a traditional poetry unit are noticeably (and intentionally) absent from this unit. I will not specifically teach poetic terms and devices in this unit, outside of what may come up naturally in conversation. Those standards, while important, are not integral to this unit and will be covered in other lessons and units in the school year. Identity and Ideology seems like a poetry unit, but it is really a discussion unit that uses poetry as a vehicle. My unit plans to mimic this unpacking process with my students. Each session of ModPo required us to come prepared to challenge ourselves and our thinking. This process can be intimidating – especially when your school experience has been in a primarily teacher-driven environment. I teach seventh and eighth grade English Language Arts in a neighborhood public school in the northwest corner of Philadelphia. My school educates students from pre-kindergarten through eighth grades. The student body identifies as 89% African American, 8% identify as more than one race, and the remaining 3% representing Hispanic, white, Asian, or Pacific Islander. The entire student body is designated as coming from a “low-income family” with 100% of students qualifying for free or reduced price lunch. We boast a highly active Family-Teacher Association; parents and families are very involved and the school is very much a part of the neighborhood community. Designated as one of Philadelphia’s community schools, our students and families participate in a weekly farmers market at the school, among other things. This unit focuses entirely on poetry by African American poets and those who center the African American experience so that my students (entirely African American) can explore their own identity and the importance of finding and sharing their own voices. I’d like students to begin to see their participation in discussion in class, and their contributions to our classroom culture as a microcosm of their participation in society at large. As students cultivate their own beliefs and opinions, strengthen their voices, and validate each others’ ideas, they will become more empowered to share their stories. For our culminating project, I’d like students to be able to choose how they feel their learning can best be represented in the community. This may take the form of leading a poetry discussion with a lower grade classroom, or even with a group of parents. It may be mirroring poetry they’ve read to reflect their own experience and presenting them to our school or local community. Students in marginalized communities often have a valid distrust of authority figures (Gorski 28). In order to create this atmosphere conducive to sharing and learning, I will focus on cultivating the potential and leadership of students through student-led small discussion and by modeling my own learning by sharing my own questions and confusion and talking through with students. To have an authentic learning experience, students need the opportunity to engage with poetry in meaningful ways (Ritchhart 10). As a ModPo seminar student, I was able to experience this authentic intellectual activity with my peers. By introducing a mini-ModPo to my students in Identity and Ideology, I will give them structures and opportunities to do and to teach each other and construct meaning collaboratively. This unit will be the foundation for discussions on other types of text throughout the year. While a group discussion on an informational text is not exactly the same as a discussion about a poem, students will have the tools and the experience to comfortably explore and question other texts in a meaningful way that allows them to think critically.

The unit will be roughly three weeks long. There will be three phases of the unit. The first phase is the introduction to exploring poetry with questions and discussion. The goal of this phase is to get students more comfortable with learning through questioning, as opposed to learning only being demonstrated through a single correct answer. An example of this phase is presented in the first lesson plan (below). This would be the kick-off lesson, but may require additional follow up lessons before moving into the next phase. Phase two of the unit, the bulk of the unit, will be close reading. Each daily lesson will follow the same general format and focus on one poem each day. To acclimate students to group discussion and equip them with the tools to organize their thoughts and express themselves clearly, I will share a different strategy in each of the first few lessons in this phase. The goal is that students will add these strategies to their toolkit and be able to use the tool(s) that are most effective for them. Lesson two (below) is an example of this close reading phase. It also shows how I may refer to previous strategies and encourage students to reflect and select what works best. The final phase of the unit focuses on writing imitation poetry. This will be the shortest phase of the unit and will refer to poems that students have already read in class. That is, they will have already analyzed and discussed a poem as readers before we embark on analyzing and imitating a poem as writers. In this unit, we will have structured lessons to imitate two poems, and students will be able to self-select a third poem to imitate. Lesson three (below) is an example of one writer’s workshop. The unit will culminate in a performance assessment that will largely be driven by student input and planning, though will likely be some form of a community poetry reading that students plan and execute together. As noted previously, this is not an assessment of their knowledge of poetry, but rather their ability to think critically, discuss confidently, and question frequently. This, of course, can be challenging to assess. My goal is to establish the conditions and norms that equip students to engage in discussion throughout the rest of the school year. This unit is intentionally lean on handouts for students. In developing habits of mind in students, I want to show and model that there are a variety of ways to organize your thoughts. A student does not need to have a specific graphic organizer in order to think through a piece of poetry. If a student develops the habit of using see/think/wonder to examine text, for example, this can take a variety of forms when written. That said, when thinking of the diverse learning needs of my students, I will depict these options on chart paper posted around the room that students can refer to at any point. As with any habit, we will practice extensively before they become internalized. Below are the highest frequency teaching strategies in this unit. Each of them is used to boost student engagement and provide low-pressure opportunities to explore thoughts and ideas. By using these regularly, my hope is that students feel comfortable in the classroom and know what the expectations of our classroom environment are. Stop and Jot – This strategy asks students to stop and quickly write down initial thoughts, ideas, or impressions of a poem or idea. The stop and jot gives students time to think and collect an idea before sharing or discussing. Jigsaw – In our mini-ModPo version of a Jigsaw, students will use this familiar strategy to become more comfortable “unpacking” words and phrases. In this jigsaw, students in a group will each be responsible for explaining a different word/phrase from the poem. Each student who shares the same word from different groups, will meet as “experts” to talk through the word together and co-construct ideas and responses. This takes some pressure and intimidation away from the process (especially when first starting). Experts will then return to their original groups to explain their word or phrase. Carousel Share – In this share, usually used in the closing of a lesson, I will ask students to come up with one word to describe either their thoughts on our poem that day, or one word from the poem that they loved, or one word to describe how they are feeling at the moment, etc. Students must only choose one word and are not called upon to explain it. This is a low-pressure way for students to engage and have fun with words. To make it more exciting, I’ll often time the carousel share to make it a race. Every student in the class shares their word by shouting in out. We’ll go up and down words, or pod by pod, depending on how student desks are arranged. Gallery Walk – In a gallery walk, students are silent observers as if visiting a gallery. In this unit, I will use the gallery walk to present images that lend themselves to deeper interpretation of a particular poem, or images that may elicit the scene or the feelings portrayed in the poem. Do Now – Each class period begins with a Do Now. This is a brief (3-5 minute) activity that serves as a warm-up for the students to engage with material that previews or sets the tone for the class period. Exit Slip – Each class period ends with an Exit Slip. This is a brief (roughly 5-10 minutes) prompt that serves as a check for understanding after each lesson. Silent Discussion – I use this most often before having a verbal discussion. In a silent discussion, students write a brief response to a prompt. In a small group format, this may mean passing along one piece of paper (like passing notes). In whole class or a larger group, students would rotate and write responses on chart paper around the room. This is a low pressure way for all students to share thoughts and see what others have to say before engaging in a verbal discussion. Student-Led Discussion – After students become accustomed to the norms and expectations of our discussions, they will take turns leading discussions themselves in small groups. Visual Prompts – Poetry is an art form, and visual prompts (using art in the classroom) can encourage students to be more creative in how the respond and engage with material. In this unit, we will use visual prompts most often as a Do Now with the structure “I think… I notice… I wonder…” to allow students to respond in a low-stakes situation to a prompt that lends itself to a more abstract interpretation. Hand Signals (Thumbs up, thumbs down; snaps or pounds, fist of five, etc.) – Hand signals are a quick way to get an idea where all students are. Most commonly I will use hand signals to find out if students agree or disagree with a particular idea. In addition, I use hand signals to gauge confidence levels (for example: “How comfortable or confident are you that you could explain what you think about this poem to a classmate? 5 = very confident and comfortable, 1 = not at all). Compass Points (Ritchhart) – Compass Points is a routine structured to engage students in reflecting on their own decision-making process as learners. Compass Points (N = what else do you need to know? S = what is your current stance or opinion on this topic? E = What excites you about this idea? W = What worries you?) gives specific categories for students to note where they are in the learning process and what they may need in order to be successful moving forward. Think Aloud – When modeling for students, the Think Aloud is when I narrate my thoughts and ideas about a poem. This is important in showing students that I too have many questions and allows me to explicitly show them that I can be vulnerable and comfortable in not having all the answers.

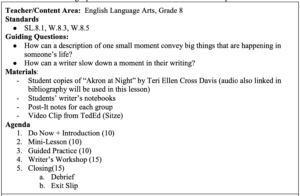

The following lessons are numbered 1-3. While Lesson 1 is the first lesson I would use in the unit, I would not follow it immediately with lessons 2 and 3. I chose to present three different types of lessons (intro to the unit, close reading, and writing focused) to show the arc of the unit. The bulk of the lessons will be versions similar to lesson 2 (targeted close reading), and lesson 3 is an example of one of the imitation poetry writing lessons that will come toward the end of the unit. While the target audience is eighth grade ELA, the lessons can easily be adapted to meet the needs and standards of sixth-eighth grade ELA and ESL classes. The lessons serve as models in which one could substitute other poems to meet the same goals of discussion. Lesson 1 Lesson 2 – This lesson would not be presented on day two of the unit, but a few days into the unit. This format will be what most of the close reading lessons (the bulk of the unit) would look like. Lesson 3 – This lesson would not be presented on day three of the unit, but would be an example of a lesson the third or final phase of the unit. I would use this lesson after completing a close reading and discussion of the poem in a previous lesson. This writing lesson would ideally not be the first exposure students had to this poem. This lesson focuses on students using a poem as a model to write their own imitation poem.

Works Cited

Bibliography for Teachers

Reading List for Students

Materials for Classroom

Appendix