Students in our public school system are exposed to the terms climate change and global warming almost regularly; however, the scientific research regarding the changes in Earth’s climate is not mandated literature in our national curriculum. This unit is a tool that should be used by teachers to provide students with inquiry-based instruction about climate change and greenhouse gas emissions, their effect on the Earth, and suggestions for preserving our natural resources. This unit is anticipated for students in Grade 3 and will help them to understand the affects of greenhouse gas emissions and the consequences on future generations, as well as how to halt and prevent future atmospheric damage.

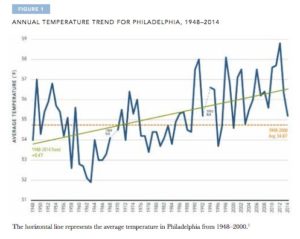

Humanity as we know it has adapted to, and lived comfortably, in the somewhat constant climate of the last few centuries. If we continue to pollute the atmosphere with carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, our future generations will be forced to adapt to an entirely different climate that may sustain more tumultuous weather patterns. In order to reduce the risks we will face because of our choices, we must educate children on protecting their natural environment. We must also instill in them the concern for their descendants. Students need to understand that they are able to act toward reducing greenhouse gasses and that the changes they make at home, school and, in the future, at work will contribute to a clean environment. This type of study is particularly important for students in the third grade because it is developmentally appropriate to be aware of, and concerned about their environment and surroundings; however, research conducted within the field of Environmental Education shows that knowledge alone does not produce the actions and changes in behavior (Steger, 2006) that are crucial to adopting a sustainable mindset. Students must understand that their daily experiences in their environments are the effects of climate change. According to the Mayor’s Office of Sustainability and ICF International’s 2015 report, “Growing Stronger: Toward a Climate-Ready Philadelphia,” in the past six years Philadelphia has experienced unpredicted extreme weather including one of the snowiest winters (2010) in history and two of the warmest summers (2015) ever recorded. (ICF, 2015) As presented in Figure 1, the data insinuates that the average temperature in Philadelphia will continue to get warmer thus suggesting that the future of the city will be under water because of the sea-level rise induced by glacier melting. As the city is in such a vulnerable state, it is vital that we expose students to this crucial information and allow them to invest their time in designing solutions. [i] NOAA. 2015. Climate at a Glance. National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved July 28, 2015 from http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/cag/ time-series/us

The enduring understanding that students will foster through this unit is that changes in our current climate are dramatically occurring. By the end of this unit students will have a comprehensive familiarity of the issues regarding climate change, and the culminating objective of this unit is for students to have hypothesized and researched some solutions to local and global climate issues. This unit is anticipated for students in Grade 3. Students spend the duration of their academic instruction in one classroom with the exception of a 45-minute Art, Computer, Gym or Music class (one-period per day, five days per week) and a 45-minute lunch block. The scaffolded objectives of this unit are as follows: The skills that students will acquire through the lessons in this unit range from career readiness skills to higher order thinking and literacy analyses skills. Through discovery and project-based learning students will gain scientific method skills and the abilities to create and conduct a research study. In this unit students will have to utilize resources in their communities such as people, water, plants, and land in order to collect data. There are a multitude of cross-curricular connections between these skills. Understanding information regarding data and visuals such as diagrams and charts are a major part of the third grade literacy standards. Non-fiction text features are studied for the scope of the entire school year. The books and documents read to and by students will provide us with opportunities to analyze the evidence and apply it to our own studies. These resources will also help scaffold non-fiction writing skills and present models for students to follow in their writing. Mathematics standards for third grade students include understanding and using operations, and also using these operations to analyze data. Students are taught data collection early in the year when they simultaneously learn to graph such information. In this unit students will see and create graphs and diagrams using data from current research as well as the research they conduct.

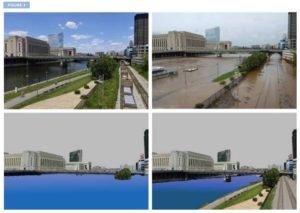

In order to deliver information to students and reach them in their Zone of Proximal Development (Vygotsky, 1896-1934) this unit utilizes a variety of STEM teaching resources and multi-modal forms of instruction at students’ developmentally appropriate learning levels. They will explore the Internet to gather information, conduct inquiry-based research, and understand scientists’ views on climate change. The course of this unit begins with activities that offer foundational concepts concerning climate change. Next, students will explore the components of Earth’s atmosphere and examine the changes that nature has experienced over the past few decades. The introductory lessons are intended to incite students’ interest in their own environmentally unfriendly, or destructive, habits. When this level of interest is achieved students will discover and use online resources to examine greenhouse gas emissions and calculate their own carbon footprints. Students should begin to express concern about their carbon emissions and begin to inquire about the impacts of climate change in their community. Students will be encouraged to take notice of their surroundings and constantly build text-to-world and text-to-text connections. While studying climate change it is crucial that students are simultaneously, or prior to this study, familiar with data collection and analyses such as translating information, creating a graph or visual representation, and interpreting that information. It is also important that students are exposed to a range of data collection tools such as surveys. These proficiencies will prove useful as students should be afforded opportunities to put their skills to practice by inquiring and surveying their community members about their findings, and use available resources to conduct hands-on projects around a hypothesis or proposed solution to the climate change issues most prevalent in their communities. Lessons on the effects of climate change across the Earth should follow the foundational lessons. Once students are knowledgeable in data collection on a large scale they will be ready to collect and analyze data in their communities. For example, following the foundational lessons on climate change around the world, students in Philadelphia should also learn about the effects of climate change in Philadelphia through various resources. When they are familiar with the city’s research they should have the chance to go into the community and begin to take data on the effects of climate change in their area. This type of exploration, called Adventure Learning (AL) by Will Steger (2006) is the most imperative component of the unit; as described by Steger, “Adventure learning is an educational approach that provides learners with opportunities to explore real-world issues through authentic learning experiences within collaborative online learning environments. Adventure Learning (AL) is a hybrid distance education approach that provides students with opportunities to explore real-world issues through authentic learning experiences within collaborative learning environments.” (Steger, 2006) Developing environmental sensitivity and potential strategies for climate sustainability are dependent on Adventure Learning. The figure above, from the Mayor’s Office of Sustainability and ICF International’s 2015 Report, is one of the most impactful photos that could be used to expose students to the realities of climate change in the city. In addition to the skill-based, teaching strategies described above, I will use research-based instructional techniques that engage students’ multiple intelligences (Gardner, 1991) within their Zones of Proximal Development (Vygotsky, 1896-1934) through deeply fascinating discussion. Turn-and-Talk: This is a technique that demands all students to collaborate with others and develop their perspective through conversation. It is a low-maintenance discussion technique that does not require any set-up or arrangement of writing surfaces. Gallery Walk: A Gallery Walk is a movement-based, station arrangement that provides opportunities to for students to interact with materials, information, and each other. It can be conducted with paper, computers, chart paper, or any resource of one’s choosing. It is an opportunity for students to challenge their own thinking and view others’ thinking from their own lenses. Socratic Seminar: As defined by the National Paideia Center, a Socratic seminar is a “collaborative, intellectual dialogue facilitated with open-ended questions about a text.” The purpose of using this technique is to require students, or participants, to carry a discussion and lead each other to a deeper understanding of the ideas with which they are learning. Students are presented with open-ended questions and use a strategic set of further questions or statement starters to support their responses. Rather than debating about a topic, students are encouraged to search for evidence that supports their opinions and help one another interpret or analyze information. For more information and resources about Socratic Seminars, visit https://www.nwabr.org/sites/default/files/SocSem.pdf. Fishbowl Conversation: This is a teaching strategy that promotes practices of contributing to a discussion and listening to others. In this type of conversation students are sitting in two “fishbowl” circles – one interior circle and one exterior circle. The students sitting in the interior circle share questions, information, and ideas with one another while those seated in the exterior circle listen and take notes. When the discussion commences the roles are reversed. This arrangement gives all students the opportunity to speak to their peers and reflect on their thinking. For more information on the “Fishbowl” method, visit https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/teaching-strategies/fishbowl. [i] M. (n.d.). Growing Stronger: Toward a Climate Ready Philadelphia. Retrieved from http://www.phila.gov/green/PDFs/Growing Stronger.pdf

Research-Based Teaching Methods

Students will engage in a range of activities from in-class note-taking to museum visitations. Students will also have opportunities to video chat with professionals who work closely with the EPA as well as professionals within industries that are contributors to the pollution of our air. Daily logs and data will be updated to support students’ scientific hypotheses. Materials: Materials: 13. After each group has presented and discussed, wrap up the discussion with a Science Notebook writing activity in which students respond to the question, “What did I learn today?” Materials:

LESSON 1: Assessing Students’ Knowledge of Climate Change

On the first day of the unit instructors should use a diagnostic assessment to understand students’ knowledge of climate change and the effects of emissions.

Time: 45 minutes

Accommodations: Print all resources for students or provide them with links or PowerPoint’s for those who have technology aids. Students who require additional support either audibly or visually may be seated closest to the instructor.

LESSON 2, 3, 4: What is Climate Change?

The purpose of these lessons is to build students’ foundational understanding of climate change, and the reasons for the increasing carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. They will use their ability and knowledge of graphing to explore the relationship between carbon emissions and atmospheric changes. These lessons are inspired by http://www.teachclimatechange.org/ and https://www3.epa.gov/.

Time: 45 minutes (each lesson)

Climate refers “to the average weather conditions in a place over many years (usually at least 30 years, to account for the range of natural variations from one year to the next). For example, the climate in Philadelphia is cold and snowy in the winter, while Miami’s climate is hot and humid.” (EPA, 2016)

Weather is, “a specific event or condition that happens over a period of hours or days. For example, a thunderstorm, a snowstorm, and today’s temperature all describe the weather. Weather is highly variable from day to day, and from one year to the next.” (EPA, 2016)

Atmosphere is a layer of gases that surround the Earth and are held in place by gravity.

Carbon Dioxide is, “a gas found in Earth’s atmosphere. Each carbon dioxide molecule is made up of one part carbon (C) and two parts oxygen (O), thus it is often written CO2.” (Rainforest Alliance, 2016)

Accommodations: Print all resources for students or provide them with links or PowerPoint’s for those who have technology aids. Students who require additional support either audibly or visually may be seated closest to the instructor.

LESSON 5, 6, 7: Weather and Climate

Students will learn and understand the differences between climate and weather through this lesson plan. They will collect local data for a defined time period and compare this data with long-term climate data regarding Philadelphia. These lessons are inspired by http://www.teachclimatechange.org/ and https://www3.epa.gov/.

Time: 45 minutes (each lesson)

Accommodations: Print all resources for students or provide them with links or PowerPoint’s for those who have technology aids. Students who require additional support either audibly or visually may be seated closest to the instructor.

JT Houghton, Y Ding, DJ Griggs, M Noguer, PJ van der Winden, X Dai. (2001) Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis. Contribution of Working Group 1 to the Third Assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press;, pp. 881, £34.95 (HB) ISBN: 0-21-01495-6; £90.00 (HB) ISBN: 0-521-80767-0. This document is a comprehensive, scientific-assessment of past and current climate patterns as well as predictions about our future climate written by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Though it was written in 2001, the panel accurately predicted the changes that we are currently experiencing. My knowledge of climate change was limited prior to my review of this document but the thorough analyses and observations provided by the researchers helped me to foster my own understandings. Global Climate Change. (n.d.). Retrieved April 12, 2016, from http://climate.nasa.gov/ There are a multitude of resources available on this site that provide facts, data and analyses of NASA’s research on climate change. The information is comprehensive and organized by topic; the learning path begins by explaining the importance of carbon dioxide as it relates to global temperature change and leads into global temperature. The organization of topics was the inspiration for my unit as the simplicity of the site appropriately scaffolds the information. Climate Change. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www3.epa.gov/climatechange/kids/documents/weather-climate.pdf This document provides background information regarding weather and how it is affected by changes in climate. Lesson plans are geared toward helping students conduct their own research to lead to independent observation and analyses. Gardner, H. (1991) The unschooled mind: how children think and how schools should teach. New York: Basic Books Inc. In order to appropriately differentiate and scaffold this unit I consider Howard Gardner’s Theory of Multiple Intelligences and the learning preferences of my students. The design of this unit accommodates all of Gardner’s eight intelligences. Harvey, Stephanie. “Bringing the Outside World In.” School Talk 5.2 (January 2000): 1. While it seems a logical task, transitioning from classroom learning to outdoor inquiry and research can be difficult. This document outlines ways to interest students in “the outside world” inside the classroom via nonfiction literature, and transitioning this interest outside the classroom. Stephanie Harvey’s points regarding student age and the decline of curiosity resonated with me as an elementary teacher as I want to support my students becoming more passionate and inquisitive about their environment as they age. Home – Climate Generation: A Will Steger Legacy. (n.d.). Retrieved June 17, 2016, from http://www.climategen.org/ Will Steger dedicated his life’s work to conserving the Arctic and exploring climate preservation. This comprehensive report sheds new insight into the climate change discussion and adds depth to basic understanding of global warming. (n.d.). Growing Stronger: Toward a Climate Ready Philadelphia. Retrieved from http://www.phila.gov/green/PDFs/Growing Stronger.pdf The general discussion of climate change across the globe prepares students to engage in research on their own locale. As I am a teacher in the city of Philadelphia my students will culminate their holistic understanding of the topic by referencing this report created by the city’s government. Lessons and Activities to Build the Foundations for Climate Literacy — Climate Change and the Polar Regions — Beyond Penguins and Polar Bears. (n.d.). Retrieved April 12, 2016, from http://beyondpenguins.ehe.osu.edu/issue/climate-change-and-the-polar-regions/lessons-and-activities-to-build-the-foundations-for-climate-literacy Lesson Plans. (n.d.). Retrieved April 12, 2016, from http://www.climatechangelive.org/index.php?pid=180 Malinowski, A. (2012). Global Warming 101 Lesson Plans for Grades 3 – 6 – Will Steger. Retrieved from http://www.camelclimatechange.org/view/article/174041 The Franklin Institute. (n.d.). Retrieved February 23, 2016, from https://www.fi.edu/climate-science (n.d.). Retrieved February 23, 2016, from http://www.forbes.com/sites/randalllane/2016/02/23/bill-gates-just-released-the-math-formula-that-will-solve-climate-change/#6b745fdf5ab8 Teach Climate Change. (n.d.). Retrieved June 17, 2016, from http://www.teachclimatechange.org/more-resources/climate-change-lesson-plans/Literature Resources

Teaching Resources

Supplementary Resources

Appendix A. Appendix B. Appendix C. Appendix D. Appendix E. Appendix F. [i] http://www.rainforest-alliance.org/curriculum/climate/activity1 [i] http://www.rainforest-alliance.org/curriculum/climate/activity1

The PA Core Standards are aligned with the Next Generation Science Standards that dictate the learning trajectory of third grade science concepts. These standards suggest the following instructional organization of science topics: The nuanced issues regarding climate change are studied in the second quarter. Students will focus on connecting precipitation to weather; explaining how air temperature, moisture, wind speed and direction make up the weather in particular places and at particular times; and identifying some systems that are found in nature and some systems that are made by humans. The overarching standard for science in grade 3 is attaining inquiry-based skills and knowledge. PA Core Standards 3.3.3.B3. Science as Inquiry 3.3.3.A4. Connect the various forms of precipitation to the weather in a particular place and time. 3.3.3.A5. Explain how air temperature, moisture, wind speed and direction, and precipitation make up the weather in a particular place and time. 3.4.3.A2. Identify that some systems are found in nature and some systems are made by humans. 3-ESS2-1. Represent data in tables and graphical displays to describe typical weather conditions expected during a particular season. 3-ESS2-2. Obtain and combine information to describe climates in different regions of the world. In addition to the science standards this unit will also help students attain skills in literacy, writing, mathematics, technology and social studies and aligns with many of the Common Core State Standards within these disciplines. CCSS Reading Key Ideas and Details: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.3.1 CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.3.2 CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.3.3 Craft and Structure: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.3.4 CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.3.5 CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.3.6 Integration of Knowledge and Ideas: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.3.7 CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.3.8 CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.3.9 Range of Reading and Level of Text Complexity: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.3.10 CCSS Writing Text Types and Purposes: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.3.1 CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.3.2 Production and Distribution of Writing: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.3.4 CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.3.5 CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.3.6 Research to Build and Present Knowledge: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.3.7 CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.3.8 CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.3.9 Range of Writing: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.3.10

Next Generation Science Standards

Ask and answer questions to demonstrate understanding of a text, referring explicitly to the text as the basis for the answers.

Determine the main idea of a text; recount the key details and explain how they support the main idea.

Describe the relationship between a series of historical events, scientific ideas or concepts, or steps in technical procedures in a text, using language that pertains to time, sequence, and cause/effect.

Determine the meaning of general academic and domain-specific words and phrases in a text relevant to a grade 3 topic or subject area.

Use text features and search tools (e.g., key words, sidebars, hyperlinks) to locate information relevant to a given topic efficiently.

Distinguish their own point of view from that of the author of a text.

Use information gained from illustrations (e.g., maps, photographs) and the words in a text to demonstrate understanding of the text (e.g., where, when, why, and how key events occur).

Describe the logical connection between particular sentences and paragraphs in a text (e.g., comparison, cause/effect, first/second/third in a sequence).

Compare and contrast the most important points and key details presented in two texts on the same topic.

By the end of the year, read and comprehend informational texts, including history/social studies, science, and technical texts, at the high end of the grades 2-3 text complexity band independently and proficiently.

Write opinion pieces on topics or texts, supporting a point of view with reasons.

Introduce the topic or text they are writing about, state an opinion, and create an organizational structure that lists reasons.

Provide reasons that support the opinion.

Use linking words and phrases (e.g., because, therefore, since, forexample) to connect opinion and reasons.

Provide a concluding statement or section.

Write informative/explanatory texts to examine a topic and convey ideas and information clearly.

Introduce a topic and group related information together; include illustrations when useful to aiding comprehension.

Develop the topic with facts, definitions, and details.

Use linking words and phrases (e.g., also, another, and, more, but) to connect ideas within categories of information.

Provide a concluding statement or section.

With guidance and support from adults, produce writing in which the development and organization are appropriate to task and purpose. (Grade-specific expectations for writing types are defined in standards 1-3 above.)

With guidance and support from peers and adults, develop and strengthen writing as needed by planning, revising, and editing. (Editing for conventions should demonstrate command of Language standards 1-3 up to and including grade 3 here.)

With guidance and support from adults, use technology to produce and publish writing (using keyboarding skills) as well as to interact and collaborate with others.

Conduct short research projects that build knowledge about a topic.

Recall information from experiences or gather information from print and digital sources; take brief notes on sources and sort evidence into provided categories.

(W.3.9 begins in grade 4)

Write routinely over extended time frames (time for research, reflection, and revision) and shorter time frames (a single sitting or a day or two) for a range of discipline-specific tasks, purposes, and audiences.