This unit explores how food choices are shaped by cognitive science, social determinants of health, and the modern food system. Students examine ultra-processed foods, marketing strategies, and environmental impacts while considering equity and sustainability. Through hands-on projects, cooking labs, and reflection, learners build agency to make informed decisions. Framed by One Health and wicked problems, the unit emphasizes critical thinking, student voice, and interdisciplinary connections between food, health, and environment.

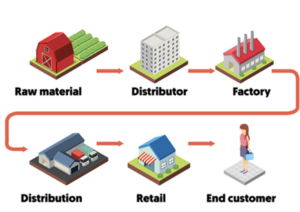

“We are what we eat,” or so the saying goes. If that’s true, my students are Doritos. Context & Rationale I observe the eating habits of dozens of students daily. Some arrive at school with styrofoam containers filled with bacon egg and cheese sandwiches with fries, others tote fried beef pastelitos (turnovers). Quite a few bring in cans of soda, or sweetened Dunkin’ Doughnuts beverages. Many others pick up school breakfast with a carton of milk or fruit juice, alongside a processed and plastic packaged breakfast food. I watch the boxes of heat-and-serve supplies delivered to the cafeteria entrance, and see students chow down on reheated pizza, mystery nuggets and defrosted vegetable medleys. Dozens of plastic take-out bags, empty chip, candy and cookie packages, and single-use plastic water bottles fill my classroom trash can at the end of each day. If this limited sample is any indication, students are surviving on processed foods. Many people, particularly those from low-income backgrounds, have many challenges in maintaining healthy diets. Zarnowiecki et al., (2014) observe that “a relatively consistent body of literature shows that children and adolescents of low socioeconomic position… are at risk of consuming poorer diets, due to lower fruit and vegetable consumption, and higher intake of snack foods, fast foods and sweetened beverages.” Work by Katre & Raddatz (2023) offer research to support that “the food behaviors exhibited by low-income families are a reflection of the shortcomings of the built environment and conventional food system,” Our food system seems to be broken. In addition an “issue brief” published by the Philadelphia School District (SDP) detailed extensive food insecurity in a significant percentage (between 11% and 30%) in most of the SDP student households. “Any severity of food insecurity has been shown to have a negative effect on students’ academic outcomes, behavioral health, and emotional wellbeing.” (Household Food Insecurity in the School District of Philadelphia: An Analysis of District-Wide Survey Results, 2021-22, n.d.) No longer surprising to me, but still shocking, is the fact that food insecure students and their families can also suffer the negative health consequences of both poor nutrition and obesity. Cheap calories can fill a person up, while not meeting the requirements of a healthy nutritious diet. Paradoxically it seems “food insecurity can lead to obesity by provoking excessive consumption of energy-dense, low-quality foods high in saturated fats and sugars such as ultra-processed foods.” (Rezaei et al., 2024) I could find no required nutrition education lessons or standards within the Philadelphia School District health (or other) curriculum on the district web-site, nor within my school’s list of health or science competencies. The General Learning Outcomes/experiences for students in Health Education (Curriculum and Instruction | The School District of Philadelphia, 2017) does list “healthy eating” as one that students should “learn information about … that is age appropriate,” a rather general recommendation amongst many. The district does partner with the The Eat Right Philly Program, which is funded (for now) by the USDA Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) program. This program offers schools that sign up, periodic lessons in some classrooms to “support… creating a healthy environment for students to learn and grow. Programs offered include engaging nutrition lessons that support the District’s Academic Framework.” According to the Eat Right Philly website they serve approx 16,000 students a year. This could be just one, or several lessons. For a district with close to 200,000 students, this means that only 8% are exposed to some limited opportunity to explore “healthy eating” in a school lesson context in any given year. As students in an agriculture, food, and natural resources class, I would like my students to consider the multifaceted consequences of food choices—on their personal health, environmental sustainability, and community health. Throughout the one-year intensive Career and Technical Education program that we call AFNR (Agriculture, Food & Natural Resources Management) we have the opportunity to explore the intertwined concepts of Social Determinants of Health and One Health. Social Determinants of Health are non-medical factors that influence a person or community’s health outcomes. For example; poverty can lead to housing options in neighborhoods far from markets selling fresh food. Poverty leads to the kind of financial stress where building repairs and ongoing maintenance is not able to be a priority; and neighborhoods with dense low-income housing will have fewer municipal services that pick up trash and clean streets, both of which leads to closer proximity to vermin, stress, and violence. (Braveman et al., 2011). Low-wealth neighborhoods often have lower levels of education and fewer trees. These factors all contribute to ill-health. One Health, as defined on the CDC web-site “… is an approach that recognizes that the health of people is closely connected to the health of animals and our shared environment.” In the public health sphere this might connect deforestation with habitat loss for animals that then are forced to live closer to humans which then cause an increase in zoonotic disease transmission. Even my well cared for backyard chickens, while a sustainable component of a backyard garden, pose an avian flu vector risk to my family and neighbors. One could also point to many environmental and climate impacts of commercial cattle or hog agricultural practices alongside the dietary impacts on heart disease in humans through the lens of One Health (Zhang et al., 2024). Both the social determinants of health and one-health paradigms expose the many interconnections between food and food supply chains, health of people and the health of our environment. The question of how to mitigate impacts is tangled in a web of connections. What is the carbon footprint of beef versus beans? How does regenerative agriculture offer a pathway toward carbon sequestration? How do I eat just one? These questions are critical, yet answering them is complicated by the overwhelming number of food choices available, and the unfortunate reality that these choices which were once the province of family tables and cultural traditions are now so heavily influenced by food companies, supply chain economics, and corporate profit motive. Ultra-processed foods dominate the modern diet (Martínez Steele et al., 2016). These foods, engineered for convenience, affordability, and hyper-palatability, provide easy access to calories packed with excessive fat, salt, and sugar—often at the expense of long-term health. These foods are implicated in a range of diet-related diseases, such as diabetes and heart disease, and along with unsustainable farming practices, energy use in processing and transportation, and packaging that contribute to a range of environmental climate impacts. Ultra-high processed foods could be the definition of “One-Unhealth.” A clear concise definition of the term ultra-processed foods has been a years-long effort in research and policy on dietary guidelines (Gibney, 2018). The definition I have long used with students is that ultra-high processed foods are products made from ingredients that would not appear in a home kitchen, or available for purchase from a supermarket. These include, but are not limited to, artificial colors, artificial flavors, various preservatives, flavor enhancers, and emulsifiers. By contrast many foods need to be minimally processed to get them from field to market or table, such as wheat that is winnowed, ground and sifted to make white flour; or olives that are pressed for olive oil. Minimally processed foods have been part of the diet of humans for over two million years, “The majority of foods comprising modern diets are processed and have been so for centuries.” (Capozzi et al., 2021). Notching up the processing to meet the demands of food company shareholders at the expense of our health is much more recent. One diet classification system called NOVA sums up UPH food as “snacks, drinks, ready meals and many other products created mostly or entirely from substances extracted from foods or derived from food constituents with little if any intact food” (American Heart Association News, 2020). This NOVA classification system is a widely used, and a useful framework to build and understand how we might influence individual eating habits and public policy around food now that our “modern” food system is so influenced by multinational companies with more regard for profit than health. “Ultra-processed products are not modified foods, recognizable as such, but formulations of industrial sources of dietary energy and nutrients, particularly unhealthy types of fat, starches, free sugars and salt, plus additives including those designed to intensify sensory impact. They typically contain little or even no intact food (Gibney, 2018). It is not only the processing of ingredients, but the flavor profiles themselves, that are engineered to not quite satiate, but that deliver excesses of calories, sodium and fat. It is purposeful that you can not “eat just one.” “Ultra Processed foods are clever manipulations of mostly unhealthy ingredients titrated to appeal to common cravings—tasty by design, but it’s all a trick,” said Dr. Devries.(Berg, 2024) There is so much more to learn about why these foods are problematic, even while they are so very tempting, which I hope students will uncover during their research. Despite the profound implications of diet on both personal and collective well-being, high school students receive little to no formal instruction in nutrition, behavioral economics, or cognitive science—disciplines that offer critical insights into how and why we make food choices. As young adults they should be gaining ever greater autonomy over their diets. They need explicit guidance, resources, and strategies to navigate the complex food landscape. Food choices are shaped not just by nutritional knowledge but by a web of psychological, social, cultural, and economic factors. Every human, from infancy onward, builds associations between flavors and fullness, food and family, meals and memories. Socioeconomic status and cultural background play an undeniable role in determining whether one grows up with home-cooked meals rich in whole foods or, more commonly, a diet dominated by UHP convenience foods. Moreover, an individual’s physiological state (e.g., hungry, tired, anxious), past experiences, and the surrounding food environment all influence decision-making. (Piqueras-Fiszman & Jaeger, 2016). Research shows that factors like sensory appeal, cognitive biases, and marketing tactics heavily impact food selection, often leading people to choose foods that are not in their long-term best interest. (Hawkes, 2007) To truly understand how food choices are made, we will need to take a multidisciplinary approach—considering aspects of sensory science, nutrition, psychology, behavioral economics, and neuroscience. …”[T]here is mounting evidence steering a move away from the conventional stance of food choice as a rational and deliberative act. Interest in opportunities to change diets that do not rely on rational decision-making and engagement of citizens is growing. To this end, the development of theory and evidence-based interventions to actively support citizen access to a sustainable and healthy diet is critical” (Ensaff, 2021). My unit will integrate insights from research in these fields to help students critically evaluate their own decision-making processes, recognize the external forces shaping their eating habits, and develop strategies for making informed, sustainable choices. Some Prior Knowledge Required Students will need to be introduced to some of the foundations of the food system before we begin to explore how decisions about eating are influenced along the food supply chain. Students will have previously been introduced to some of the many steps along the food supply chain from producer to consumer, and the complexities of multiple intersecting chains for many of the common foods we eat. The supply chain for a broiler chicken seems simple. Hen to egg to chick to adult. But of course, there is an adjacent chicken feed supply chain growing grains and soybeans which are harvested, processed and shipped from multiple locations to processing and packing and feeding locations. Even the Chick to Hen to Egg (and back to Chick in some cases) part of the chain are at a minimum three separate businesses, with packing and shipping between them. The cardboard shipping boxes, growhouses, pens, feed and water systems are entire industries with their own adjacent supply chains. Students will have some of this background knowledge when we dig into considering the food supply chain as a series of “value chains.” The idea of a value chain is that raw ingredients have a value that can be increased or decreased by how they are handled or processed. Adding value along the supply chain is always the goal. The goal of processing foods is to preserve or increase economic value, such as to prevent spoilage (drying, canning) or to create a product that is more valuable than the sum of its parts (chocolate bars vs. cocoa beans, sugar and cocoa butter sold as ingredients). Processing can lock in nutritional value – peas harvested and frozen right in the field they were grown, cooked and served months later will likely have many more vitamins than “fresh peas” picked in Florida and sold in Philadelphia two weeks later. Canned tomatoes make use of tomatoes that would spoil before getting to market, and have more lycopene available to the eater than eating a similar quantity of fresh tomatoes. (Rickman et al., 2007) A deeper dive into processing will show a wide range of variation in nutritional and economic values at various stages from harvest through processing and sale. This review will highlight specific places along the food supply chain where value is added, using the lens of social determinants of health or one-health, rather than simply economic value. If strawberries are harvested in a hot field and not cooled promptly they spoil much more quickly. These strawberries clearly have lost significant economic and nutritional value. Strawberries could be harvested, properly cooled, carefully packed and shipped, and then mixed with equal parts sugar and some preservatives and used to fill a strawberry pop tart. This would also be considered a reduction in the strawberries nutritional value, but not economic value. Looking at various specific examples of ingredients morphing and mixing with other ingredients to create products will help students understand the competing priorities faced by farmers, food, businesses, and consumers. Several lessons will cover this food chain, value chain and basics of the concepts of environmental consequences of food production, particularly the contrast between industrial agriculture and regenerative farming. The unit prior to this one will specifically introduce the concept of Social Determinants of Health and the paradigm of “One-Health” as it relates to AFNR. In a unit called Growing a Sustainable Future , students grapple with with the influence that agricultural practices have had on the health of our environment and ourselves. This foundation will hopefully prepare them for the complex questions coming next – why most of us actually make choices regularly that are not optimal for our health despite knowing better. What are the influences that have shifted human’s attention, spending and ultimately eating habits from the most nutritious options to the ones that power a multi-billion dollar industry in unhealthy foods? What Does The Science Around Making Healthy Choices Offer? A very cursory overview. There is evidence that school-based interventions [on dietary health] can be effective. A key theme is the value young people place on choice and autonomy in relation to food. Behavior takes place in social environments, and efforts to change it must therefore take account of the social context and the political and economic forces which act directly on people’s health regardless of any individual choices that they may make about their own conduct (Kelly & Barker, 2016). Knowing that school based interventions should be helpful, I am setting out to offer our students a collection of opportunities to engage with ideas that they might use in the social environment of our shared classroom, and as potential leaders/influencers of our school community. This section is an overview of a wide range of the paradigms and primary and applied research strategies around food choices, that might be useful for students to know about, and then apply, or to guard themselves against. Adolescents are in the midst of significant growth and brain development, especially in areas related to impulse control, planning, and experiences of social pressure. The prefrontal cortex, which will influence long-term decision-making, has not matured fully. The limbic system, which processes rewards and emotions, is active. So teens often prioritize short-term rewards, and can have challenges in self-regulation. Little to no thought of long term health consequences will get between a teen and a taki. While a young person’s brain might not be mature, there is much to be gleaned from cognitive science research related to weight loss and nutrition education. This body of work offers some suggestions for looking at psychological and research based strategies that both teach students how they might implement accumulated research to impact their own dietary choices, and/or to introduce some of these concepts before teaching them and reveal after the fact if changes can be measured to demonstrate a point. Given that “[p]reventing obesity in adolescents and young adults may be particularly critical, as the majority of overweight youth maintain their weight status into adulthood,”(Magarey et al., 2003) these lessons will be useful. One study showed that appealing to teens’ emerging identity, the influence that peers have on their behavior, and their desire for autonomy can be more effective in shifting attitudes than simply providing nutritional information. For instance, framing healthy eating as an act of rebellion against manipulative food industry marketing has been shown to increase resistance to junk food ads (Bryan et al., 2016). Another strategy that has shown to be effective are programs (Maria Elena Capra et al., 2024) that emphasize how healthy eating supports strength, energy, and athletic or academic performance rather than more than abstract messages about health disease prevention. It will be interesting to try introducing students to some behavioral science concepts such as choice architecture—the way choices are presented, such as opt in vs. opt out, or setting things up to have healthy choices more easily accessed—as a means to guide their own, and other’s behavior, without restricting freedom. “The real magic underlying the opt-out, though, is simple: Action is harder than inaction” (Bucher, 2017). Staff could set up situations where students have choices and track student behavior, and then reveal how (if) their behavior changed. Students could also observe how food stores place quick tempting (unhealthy) items at the register and propose strategies to promote healthful choices. Students could then be invited to predict the effect of simple changes in the school environment, or that they could set up at home, or that they could use to counter the marketing plans of every supermarket-which might shift their own food choices: Another interesting idea is learning about the Decoy Effect. Imagine you’re at a movie theater and see these popcorn prices; Small: $3, Large: $7. Maybe you think, “Hmm, $7 is too much. I’ll just get the small one.” But suppose the theater offers a third option: Small: $3, Medium: $6.75 Jumbo: $7 Now the large (jumbo) popcorn looks like a great deal—just 25¢ more than medium—so you’re more likely to buy it. That medium option is a “decoy”: it’s not really meant to be chosen, but it makes the large seem like a smarter choice. This Decoy Effect is used in marketing everything from fast food to iphones, to influence what customers buy—without them realizing it. In the activities section students will engage in a simple activity making purchasing decisions, which will be revealed to have been influenced by this decoy effect. This may help them consider how to use this effect to their advantage, or at least recognize when a business is attempting to manipulate their choices. For success, we need to develop supportive and nurturing food choice architecture that safeguards better choices, in contrast to existing choice architecture which often challenges and, in some cases, undermines favourable diets. (Ensaff, 2021) Other ways to influence food choices, using “choice architecture” techniques include: Convenience and Placement: Place fruits and vegetables at the front of the cafeteria line and at eye level. Make UHP snacks less accessible or require extra steps to access them. Default Options: Serve vegetables as the default side dish, with an option to request something else. Default options tend to be accepted without conscious deliberation. Portion Sizing and Containers: Use smaller containers for UHP snacks and larger bowls or plates for vegetables to encourage different portion norms. Another behavioral economics paradigm is the influence of Social Proof (aka conformity) and Norms: People tend to go with the herd (Pilat & Krastev, 2024). If we were to highlight that “many students at this school eat vegetables daily” we might be able to shift perceived norms and motivate students to “conform” to this norm. I could imagine that once our seniors complete this unit and have actually changed (some) of their eating habits, there could be a social proof ripple effect. Students might be able to track their own behavior changes, and use this data to influence their peers. This opportunity to influence younger peers might even make the work we do “sticky-er.” Students could also gain agency by requesting to implement techniques that they learn about which work because they reduce the cognitive load of making a healthy choice and harness subconscious biases like inertia and conformity. According to Self Determination Theory (SDT) people are more likely to adopt behaviors when they feel autonomous, competent, and connected. “According to SDT, the ways individuals regulate their behaviors vary on a self-determination continuum” (Carbonneau et al., 2021). Our AFNR program and classroom environment has many opportunities for students to participate in more food-related decisions than they may have had elsewhere, and to make connections with each other, with me, with nature and with community partners. During both structured and loosely structured food labs students plan weekly classroom cooking projects, work on multi-week projects with outside partners such as Eat Right Philly, grow vegetables in a school garden, and create social media content about healthy food. Recognizing that these opportunities promote self-determination could help support budgeting time and/or funding for these activities. The concept of cognitive reappraisal, “which involves changing the meaning of a stimulus to modify its emotional impact, has also shown promise for regulating food craving and consumption” (André Mamede et al., 2024). Students exploring this cognitive science concept could consider how one thinks about a stimulus. Maybe by topics such as: exploring the cultural significance and flavors of different vegetables; debunking myths that healthy food is boring or tasteless through cooking demos or taste tests; engaging students in storytelling about food memories and cultural traditions that involve whole, plant-based ingredients using such resources as the Heritage Food Pyramids (Explore Heritage Diets – OLDWAYS – Cultural Food Traditions, 2024). We can teach students about cognitive biases (e.g., present bias, loss aversion) and their role in food decision-making. We can analyze food marketing strategies and their psychological influence on consumer behavior. Perhaps students will investigate how sensory cues (texture, color, smell) and psychological factors, such as stress, impact eating behavior. When students learn how food marketing has co-opted facts, and food companies have used food science around “bliss-point” to sell us more things that are really bad for our health, they might be outraged. Or perhaps they could be motivated to use these techniques to “sell” alternative options (sparkling juices v. soda; home-made popcorn or trail mix v. packaged snacks; baked v. fried pastalitos). Additionally, helping students set and track small, achievable goals (e.g., “I will add one vegetable to lunch this week”) enhances their sense of competence and progress. Making this easier and celebrating small wins (with some self assessment tools – public or private tbd) could help shift internal narratives about what “healthy eating” looks and feels like. This is a complicated subject, and could diverge quickly into conversations about food access, food security, poverty, and other so-called wicked problems that impact what decisions individuals make around food. While much of this unit is looking at the influences on individual choices, we will soon connect to bigger, more wicked, socio-cultural problems. Wicked problems are generally considered to be complex problems with no single solution, and many interconnected causes – think climate change, poverty, homelessness, education. I do have several lessons (The Power of Sustainability: Growing Climate Problem Solvers, 2025) exploring how to think about and engage with wicked problem solving, which includes design thinking strategies, some resources to engage with complexity. Exploring how we can learn to make better individual choices by understanding the way we are manipulated and manipulate ourselves when we make eating (and other) decisions in no way obviates the need to work collectively on addressing the harm caused by food businesses and the real challenge of cheap calories on our individual and collective health. “Don’t eat anything your great-great grandmother wouldn’t recognize as food. There are a great many food-like items in the supermarket your ancestors wouldn’t recognize as food. Stay away from these.” – Michael Pollan

Lessons and Activities: Lesson 1: Food Decisions – Why Do We Eat What We Eat? What Shapes Our Food Choices? We begin with a simple question: “Why did you choose what you chose”? Students jot down everything they remember eating in the past 24 hours. We use this data to build a shared class map of influences (ads, culture, taste, habits, cost, mood), and introduce behavioral science concepts like default options, impulse, and availability bias. Students will start their own food log that they’ll maintain throughout the unit, which will serve as the basis for later reflection and analysis. Lesson 2: Food and Mood – How What We Eat Can Impact our Behavior Mini-Lecture & Ted Talk Ed Puzzle: Overview of what is known about how food affects cognition, mood, focus. Kitchen Lab: Students structure a simple lab to compare how they can monitor how they and their classmates feel after two different afternoon snacks (whole vs. ultra-processed). This might be combined with nature walk, where availability of a healthy snack could impact total energy levels. Lesson 3: Ultra-Processed Foods (UPFs): What Are They and Why Are They Everywhere? Mini-Research Project – small groups each learn about and report out using this tool to the group one food classification system. Lesson 4: Grocery Store Choice Architecture & Cognitive Load We take a grocery store tour. Students are asked to observe where snacks are placed, how pricing works, and which foods are made easier to grab. We unpack strategies like anchoring, upselling, and decoy pricing. Then, using store flyers or online apps, students plan a snack shopping plan – with a group budget, with a goal of balancing nutrition, taste, and marketing traps. Field Trip or Virtual Tour: Supermarket Field Study Discussion: what did they notice? How did the supermarket reinforce what they learned about “choice architecture.” Lesson 5: Sensory Science – Why Taste Matters Students taste and rate vegetables prepared in different ways—raw, roasted, with spices, or dips. We discuss how presentation, color, and smell affect perception. Then students consider how things like hunger, distraction, or peer influence shape taste experience. Review and reflect on their earlier food journals – Food & Mood Journal questions. The takeaway: preferences aren’t fixed—they’re shaped by context and exposure. Taste Test Lab: Sample vegetables cooked different ways. Lesson 6: Social Determinants of Health & One Health We explore the paradox: How can we know so much and make such bad decisions? AND How do structural factors shape what is available and affordable? How are these related? Activity: Snack Audit – investigate ingredients on common snacks. Ingredients, health claims, additives, prices. What influences the choices to eat these foods? What role do marketing, habits, and availability play? Mini-Lecture: Contrast personal choice vs. structural barriers like food deserts, pricing, zoning, and advertising Lesson 8: Cooking for Cognitive Control Students share family or cultural dishes and the stories behind them. Then we pivot: What happens when we have too many choices—or too little time or money? Through case studies, we explore how decision fatigue leads to defaulting to the quickest or most marketed option. In a hands-on cooking session (in class or home kitchen), students prepare simple dishes featuring affordable, nutrient-dense foods: stir-fry, veggie wraps, roasted root veggies, or healthy snacks like hummus and crudite. Each team explains how their dish meets the day’s goals. Reflections tie back to flavor, cost, and behavior: Did prepping food yourself change how you feel about it? Mini-Lesson: make explicit how cultural influences are/could be huge in the question of “what will I make for dinner.” Compare and contrast African, Asian and Latino Heritage food pyramids. Student activity: list your three favorite meals eaten at home, how often are they eaten (in rotation- such as meatloaf mondays, taco tuesdays- or seasonal etc.). Who makes them usually? Who else knows how? Mini-lesson on Cultural_Traditions_Cognitive_Load_Lesson.pptx (make this more interesting): Student Fact Sheet Small Group Discussion – each group takes one of these prompts to consider how cultural traditions lighten cognitive load Lesson 9: Fast & Slow Food Systems We compare shopping receipts or use mobile apps to “shop” for 1 day of meals at different stores—Whole Foods, Save-A-Lot, corner stores, farmers markets. Students build a price-per-calorie and price-per-nutrient table. Then we tackle big questions: Why are chips cheaper than carrots? What role does policy play in food prices? Is it truly a choice if healthy food is inaccessible? We will also consider the ideas within the book “Thinking Fast & Slow” and resources from The Decision Lab to explore system 1 and system 2 thinking (see below) Discussion: Consider both Fast Food & Slow Food. Consider Fast Thinking & Slow Thinking What are “system 1 & system 2 thinking?” How can these concepts help us as we work towards better decision making. Activity: System 1/System 2 Food Choices Quiz & reflection . Visit and answer questions about the Slow Food movement. Performance Task:Guided Reflection on how to use resources from places like the Decision Lab to influence ourselves and/or others to make “better decisions” around food. Lesson 10: Nudge Theory in Action: Small Changes, Big Impact Students work in small groups to identify a food-related challenge in their school or home—then design a “nudge” solution using behavioral principles. Ideas might include signage near cafeteria or B10, setting up healthy food grab-and-go bins, or cafeteria layout tweaks. Students pitch their ideas with sketches, slogans, or mini-posters, and vote on one to potentially pilot in school. This could also be something they design for their own personal life – spend Sunday afternoon batch cooking for a few meals. Design Challenge: Students create and pitch an intervention to improve food choices in school/home. Other lessons to consider/extensions: We present a real challenge: Plan a day’s worth of meals for a family of four on a $25 budget, using SNAP eligibility guidelines. Students work in groups to consider taste, balance, cost, and time. They’ll present their plan and reflect on compromises and creative solutions. Visual aids like MyPlate and Oldways Heritage Pyramids are used for inspiration. Cultural flexibility is encouraged. In a hands-on cooking session (in class or home kitchen), students prepare simple dishes featuring affordable, nutrient-dense foods: stir-fry, veggie wraps, roasted root veggies, or healthy snacks like hummus and dippers. Each team explains how their dish meets the day’s goals. Reflections tie back to flavor, cost, and behavior: Did prepping food yourself change how you feel about it? Students revisit their food logs and write a short reflection: What have I learned about how and why I eat the way I do? What’s one change I want to keep or try? Each student chooses from a choice board of final projects: a poster, infographic, short video, recipe demo, or food story zine. These are displayed in the classroom, school lobby, or shared with families during Green Career Day.

Activity: Students recall their food choices for 24- 48 hours using this mindful eating journal and reflect on what influenced each choice (cost, taste, habit, ads, emotions, etc.). Students complete a quick Decoy Effect Question set.

Discussion/Mini Lesson: Intro to behavioral economic concepts, choice architecture opt in/opt out, decoy effect…

Check for Understanding/Performance Task: Complete Food Decision Worksheet, and add to class collaboration board (post-its on white board) to start to map visible and invisible influences on food choices.

Check for Understanding/Performance Task options: Participate in one of these food & mood challenges or design a food and mood menu for yourself for a day or two. 3-6 meals with reasons why each menu item was chosen.

Activity: Food Audit – include lots of Snack wrappers and fresh food. NOVA classification activity.

Research/Review: Explore the NOVA system and health/environmental impacts of UPFs. Students select one aspect from a choice board, and create a group slide show.

Check for Understanding/Performance Task: Choose: Infographic comparing a whole food vs. an UPF version OR use this audit tool to reflect on one mealBehavioral Economics & the Grocery Game

Check for Understanding/Performance Task: Propose three specific changes to the neighborhood supermarket, corner store or cafeteria to promote healthier choices (Check out Food Trust’s Corner Store initiative). Identify reasons for choices using vocabulary/concepts from lesson content.Taste Tests & the Psychology of Flavor

Discussion: Explore the psychology of taste, “bliss point,” and food engineering. How do companies use the physiology of taste to “manufacture binging” and other unhealthy eating tendencies?

Check for Understanding/Performance task: Quiz on food engineering. Food journal reflections.Obese and Undernourished? Personal Choices in a Broken System

Mapping Activity: Use neighborhood maps to identify food access issues. using USDA Food Access Research Atlas), students identify: Supermarkets vs. corner stores, Fast food density, Transit access (connect or create Story map?)

Check for Understanding/Performance: Guided Notes and/or an annotated map with at least two examples of structural barriers to healthy food access. A brief explanation of how these relate to social determinants of healthCooking Lab – Choices are good, or are they? Cognitive Load & Cultural Traditions

Hands-On: Teams plan and prep simple meals that maximize nutrition, minimize cost/cognitive load.

Discussion: How routines and meal prep reduce decision fatigue.

Check for Understanding/Performance Task: Weekly meal planner (worksheet with budget) with prep strategies (buy and prepare in bulk such as batch of beans to serve with rice and veg one day, burritos another and bean/veg soup for the freezer for a few weeks hence) and/or Too Many Choices, Not Enough BrainpowerThe Price of Eating Well

Research Stations: Students explore intersections of food, climate, equity, and health. Examples of slow food, fast food, slow decisions influence & fast decisions influences..Design a Nudge

Can include: default veggie trays, fridge signs, class taste test, snack swaps.

Check for Understanding/Performance Task: Answer questions that demonstrate an understanding choice architecture strategies and/or present a design challenge idea.

Meal Planning ChallengeCooking Lab – Quick, Affordable & Delicious

Reflection, Posters, and Action Plans

American Heart Association News. (2020, January 29). Processed vs. ultra-processed food, and why it matters to your health. Www.heart.org. https://www.heart.org/en/news/2020/01/29/processed-vs-ultra-processed-food-and-why-it-matters-to-your-health André Mamede, Boffo, M., Gera Noordzij, Semiha Denktaş, & Wieser, M. J. (2024). The effect of cognitive reappraisal on food craving and consumption: Does working memory capacity influence reappraisal ability? An event-related potential study. Appetite, 193, 107112–107112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2023.107112 Berg, S. (2024, November 8). What doctors wish patients knew about ultraprocessed foods. American Medical Association. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/public-health/what-doctors-wish-patients-knew-about-ultraprocessed-foods# Braveman, P., Egerter, S., & Williams, D. R. (2011). The Social Determinants of Health: Coming of Age. Annual Review of Public Health, 32(1), 381–398. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101218 Bucher, A. (2017, August 25). Behavior Change Truth: Action Is Harder Than Inaction | Amy Bucher, Ph.D. Amy Bucher, Ph.D. | Applied Behavioral Science for Health and Well-Being. https://www.amybucherphd.com/behavior-change-truth-action-is-harder-than-inaction/ Capozzi, F., Magkos, F., Fava, F., Milani, G. P., Agostoni, C., Astrup, A., & Saguy, I. S. (2021). A Multidisciplinary Perspective of Ultra-Processed Foods and Associated Food Processing Technologies: A View of the Sustainable Road Ahead. Nutrients, 13(11), 3948. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13113948 Carbonneau, E., Pelletier, L., Bégin, C., Lamarche, B., Bélanger, M., Provencher, V., Desroches, S., Robitaille, J., Vohl, M.-C., Couillard, C., Bouchard, L., Houle, J., Langlois, M.-F., Rabasa-Lhoret, R., Corneau, L., & Lemieux, S. (2021). Individuals with self-determined motivation for eating have better overall diet quality: Results from the PREDISE study. Appetite, 165, 105426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2021.105426 Curriculum and Instruction | The School District of Philadel. (2017). Curriculum and Instruction – the School District of Philadelphia. https://www.philasd.org/curriculum/#health Ensaff, H. (2021). A nudge in the right direction: the role of food choice architecture in changing populations’ diets. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 80(2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0029665120007983 Explore Heritage Diets – OLDWAYS – Cultural Food Traditions. (2024, July 24). OLDWAYS – Cultural Food Traditions. https://oldwayspt.org/explore-heritage-diets/ Gibney, M. J. (2018). Ultra-Processed Foods: Definitions and Policy Issues. Current Developments in Nutrition, 3(2). https://doi.org/10.1093/cdn/nzy077 Hawkes, C. (2007). Regulating and Litigating in the Public Interest. American Journal of Public Health, 97(11), 1962–1973. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2006.101162 Household Food Insecurity in the School District of Philadelphia: An Analysis of District-Wide Survey Results, 2021-22. (n.d.). https://www.philasd.org/research/wp-content/uploads/sites/90/2023/05/Food-Insecurity-in-SDP-2021-22-May-2023.pdf Katre, A., & Raddatz, B. (2023). Low-Income Families’ Direct Participation in Food-Systems Innovation to Promote Healthy Food Behaviors. Nutrients, 15(5), 1271. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15051271 Kelly, M. P., & Barker, M. (2016). Why is changing health-related behaviour so difficult? Public Health, 136(136), 109–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2016.03.030 Kim, E. (2013). The Amazing Multimillion-Year History of Processed Food. Scientific American, 309(3), 50–55. https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican0913-50 Leonard, J. A., Duckworth, A. L., Schulz, L. E., & Mackey, A. P. (2021). Leveraging cognitive science to foster children’s persistence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 25(8), 642–644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2021.05.005 Magarey, A. M., Daniels, L. A., Boulton, T. J., & Cockington, R. A. (2003). Predicting obesity in early adulthood from childhood and parental obesity. International Journal of Obesity, 27(4), 505–513. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0802251 Maria Elena Capra, Stanyevic, B., Giudice, A., Monopoli, D., Nicola Mattia Decarolis, Esposito, S., & Giacomo Biasucci. (2024). Nutrition for Children and Adolescents Who Practice Sport: A Narrative Review. Nutrients, 16(16), 2803–2803. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16162803 Martínez Steele, E., Baraldi, L. G., Louzada, M. L. da C., Moubarac, J.-C., Mozaffarian, D., & Monteiro, C. A. (2016). Ultra-processed foods and added sugars in the US diet: evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 6(3), e009892. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009892 Pilat, D., & Krastev, S. (2024). Social proof. The Decision Lab. https://thedecisionlab.com/reference-guide/psychology/social-proof Piqueras-Fiszman, B., & Jaeger, S. R. (2016). The Incidental Influence of Memories of Past Eating Occasions on Consumers’ Emotional Responses to Food and Food-Related Behaviors. Frontiers in Psychology, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00943 Rezaei, M., Fatemeh Ghadamgahi, Jayedi, A., Pishva Arzhang, Mir Saeed Yekaninejad, & Azadbakht, L. (2024). The association between food insecurity and obesity, a body shape index and body roundness index among US adults. Scientific Reports, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74108-x Rickman, J. C., Barrett, D. M., & Bruhn, C. M. (2007). Nutritional comparison of fresh, frozen and canned fruits and vegetables. Part 1. Vitamins C and B and phenolic compounds. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 87(6), 930–944. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.2825 The 17 Sustainable Development Goals. (2025). United Nations. https://sdgs.un.org/goals The Power of Sustainability: Growing Climate Problem Solvers. (2025a). Teachers Institute of Philadelphia. https://theteachersinstitute.org/curriculum_unit/the-power-of-sustainability-growing-climate-problem-solvers/ The Power of Sustainability: Growing Climate Problem Solvers. (2025b). Teachers Institute of Philadelphia. https://theteachersinstitute.org/curriculum_unit/the-power-of-sustainability-growing-climate-problem-solvers/ Zarnowiecki, D., Ball, K., Parletta, N., & Dollman, J. (2014). Describing socioeconomic gradients in children’s diets – does the socioeconomic indicator used matter? International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 11(1), 44. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-11-44 Zhang, G., Qiu, Y., Pascal Boireau, Zhang, Y., Ma, X., Jiang, H., Xin, T., Zhang, M., Tadesse, Z., Wani, N. A., Song, J., & Ding, J. (2024). Modern agriculture and One Health. Infectious Diseases of Poverty, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-024-01240-1 Thaler, Richard & Sunstein, Cass. Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness Monteiro, Carlos et al. “The Classification of Ultra-Processed Foods” (NOVA framework) Nestle, Marion. Food Politics: How the Food Industry Influences Nutrition and Health Moss, Michael. Salt Sugar Fat: How the Food Giants Hooked Us Pollan, Michael. The Omnivore’s Dilemma (Adult or Youth Edition) Foer, Jonathan Safran. We Are the Weather: Saving the Planet Begins at Breakfast Montgomery, David. Growing a Revolution: Bringing Our Soil Back to Life Training in cognitive strategies reduces eating and improves food choice – PubMed The Neglected Role of Food Processing Companies in Shaping Human and Planetary Health The role of reinforcement learning and value-based decision-making frameworks in understanding food choice and eating behaviorsThe role of reinforcement learning and value-based decision-making frameworks in understanding food choice and eating behaviors How food corporations manipulate you into eating more junk food | U-M LSA Department of Psychology “Nudge” Yourself Toward Better Choices | Psychology Today System 1 and System 2 Thinking – The Decision Lab Other Resources & Readings for Staff & Maybe Students

PA State Standards, Common Core, and AFNR CTE Competencies ELA Science & Technology Career & Technical Education (AFNR Pathway) Career Readiness & Community Engagement