Classroom Context

I am a fifth-grade general education teacher at A.S. Jenks Elementary School. Our school is located in South Philadelphia. It is a culturally diverse school where 20% of our students are English Language Learners.

In my classroom, I teach all four core subjects: English Language Arts, Math, Science, and Social Studies. In English Language Arts class, we engage with fiction and nonfiction texts to write analytical essays, have text-based discussions, and create presentations and creative writing projects. In the fifth-grade math curriculum, we focus on developing our understanding of fraction and decimal operations as well as important geometry concepts. In science, we cover several topics, including ecosystems, outer space, and chemical reactions. Finally, our social studies class focuses on American history from Indigenous peoples to the American Revolution.

Introduction to Cognitive Science Seminar Narrative

Part I: The Role of Logical Reasoning

When I enrolled in the Cognitive Science TIP seminar, I hoped that I would gain new understanding of my students’ learning processes so that I could more efficiently teach the vast amount of content that my students need to master in fifth grade. I thought that perhaps I would use the content of the TIP seminar to rework some lessons that I teach at the beginning of the year about brain plasticity and the importance of adopting a growth mindset.

However, my experience in the seminar took me in a different direction. In the third seminar session, we discussed logical reasoning. Cognitive scientists are interested in logic because it is a normative model for how people should reason. Humans often use logical reasoning imperfectly or do not use logical reasoning for many tasks. However, understanding formal logic models can help us understand how actual people deviate from that model when they are making decisions or solving problems. Understanding formal logic can also help us to build effective artificial intelligence models and understand computational concepts.

During the seminar session on logic, we began by discussing the definition of a valid argument. An argument is deductively valid when its conclusion logically follows from its premises. For instance, the following set of statements is a valid argument:

Premise: It is snowing or it is raining.

Premise: It is not raining.

Conclusion: It is snowing.

Validity is related to the structure and form of the argument rather than its absolute “truth” in the real world. An argument is sound if it is valid and the premises are actually true. However, there are arguments that are valid but not sound. For example, the following set of statements is a valid argument that is not sound:

Premise 1: All plants have flowers.

Premise 2: Corn is a plant.

Conclusion: Corn has flowers.

The argument is structurally valid, but due to the false nature of Premise 1, the argument is not sound.

We continued on to discuss statement logic, a formal language for considering validity. Statement logic uses specific notation to show certain logical connectives, such as conditional statements. For instance, the statement, “If it is raining, then I will stay inside,” could be shown as:

A = It is raining.

B = I will stay inside.

A → B.

Finally, we learned how you can construct truth tables to tell you how the truth-value of a compound statement depends on the truth-values of components. Essentially, truth tables provide a systematic way to determine whether or not an argument is deductively valid. In a row where all of the premises are true, the conclusion must be true as well for the argument to be valid.

This seminar session about logic made me think about areas of the fifth-grade curriculum that relate to formal logic. In my fifth-grade math class, students must employ logical reasoning when we study polygons. Students use conditional statements when they use attributes to categorize shapes (“If it has two sets of parallel sides and four right angles, then it is a rectangle.”). They must also use conditional statements to understand that a shape can fall into multiple categories (“If it is a square, then it is also a rectangle”). This is an example of this type of task in our Illustrative Math curriculum workbook:

| Always, Sometimes, or Never

Write always, sometimes, or never in each blank to make the statements true,

- A rhombus is _________ a square.

- A square is ___________ a rhombus.

- A triangle is ___________ a quadrilateral.

- A square is ____________a rectangle.

|

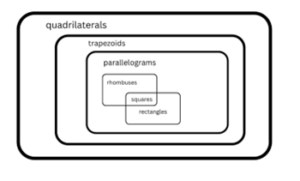

This unit tends to be a challenging one for my students. They struggle to make deductively valid arguments based on a set of premises about a shape. For instance, a question might present them with premises (The shape has four sides. It has two sets of parallel sides) and they have to deductively reason that the shape could be called a polygon, a quadrilateral, or a parallelogram (but not necessarily a rectangle, rhombus, or square). Another aspect of this unit that my students often struggle to understand is that the inverse statement of a true conditional statement is not necessarily valid. For instance, “If it is a square, then it is also a rectangle” is true, but “If it is a rectangle, then it is also a square.” is not true. They also tend to identify a shape with only its most obvious category. For instance, they can recognize that a shape is a square but have difficulty recognizing that it is also a rhombus, rectangle, parallelogram, quadrilateral, and polygon.

While these types of tasks are a relatively small part of the fifth-grade math curriculum, I explored the role of these tasks in my students’ mathematical futures. First, I considered that this geometry unit serves as a prerequisite to future geometry proofs that students will encounter in high school. According to an International Commission on Mathematical Instruction (ICMI) document on the role of proof and proving in math, “For mathematicians, proof varies according to the discipline involved, although one essential principle underlies all its varieties: To specify clearly the assumptions made and to provide an appropriate argument supported by valid reasoning so as to draw necessary conclusions,” (Hanna & de Villiers, 2008, p. 329). This geometry unit clearly meets the ICMI’s definition of proof, as students need to make appropriate arguments based on a set of assumptions to draw conclusions about shapes.

The ICMI has argued that proof and proving, “can provide a way of thinking that deepens mathematical understanding and the broader nature of human reasoning,” (p. 330), and therefore, “are at once foundational and complex, and should be gradually developed starting in the early grades,” (p. 330). This ICMI guidance further emphasized to me that developing my students’ competence with these tasks was a worthwhile pursuit for my curriculum unit.

Additional research convinced me that not only should I focus on my students’ skills related narrowly to mathematical proofs, but also on their logical reasoning skills more generally. According to a 2007 study, “logical competence at the beginning of their school career predicted children’s mathematics learning 16 months later and might therefore be a causal factor in this learning,” (Nunes et al., 2007, p. 157). Logical competence was predictive of students’ growth in mathematics even when researchers controlled for general cognitive ability and working memory. The same study found that it is possible to improve students’ performance on a test of logical competence through a relatively small amount of training. This research indicated to me that designing lessons to directly impact my students’ grasp of logical reasoning might help to improve their overall math achievement in my classroom and in the future.

Overall, the seminar session on logical reasoning and my subsequent independent research led me to think more deeply about the fifth-grade math curriculum’s geometry unit. I began thinking that I could leverage this geometry unit to positively impact my students’ future math success and their ability to use logical reasoning to solve problems across domains.

Part II: Heuristic Detours from Logical Reasoning

While the seminar session on logic covered optimal reasoning methods, the subsequent seminar session examined how humans actually reason and judge. This session shed some light on the difficulty my students have with geometry questions involving proof and proving.

Overall, although cognitive scientists use logical reasoning to model rational ways to solve problems, people are realistically limited by various factors, such as memory and attention. People also use reasoning shortcuts known as heuristics that differ from optimal logical reasoning. While these heuristics are often useful for quickly determining an answer, they do not always yield correct, logical answers.

This session forced me to think about possible heuristics my students may be employing that cause them to struggle with these geometry concepts. It also pointed me toward possible strategies for fostering their logical reasoning development to succeed with these types of problems.

At the beginning of the lecture, Dr. Richie presented us with a task from a study known as the Wason Card Task (Wason, 1968). In this task, participants were presented with the statements: Each card has a letter on one side and a number on the other. If there is a vowel on one side, then there is an even number on the other side. Then, participants were presented with four cards: U, T, 6, 3 and asked which cards they would need to turn over to determine if the statements are true. In the original study, less than 10% of participants chose the correct cards (U and 3). However, a later study with a logically identical task that was related to a social rule instead of an abstract rule had different results. In this study (Cosmides & Tooby, 1992), participants were presented with the rule, “If you are drinking alcohol, then you must be over 18,” and cards that had an age on one side and beverage on the other. When presented with the cards 16, 25, soda, and beer, a higher percentage of participants were able to correctly identify 16 and beer as the cards they would need to turn over to prove the rule true. These studies indicate that reasoning can be domain-dependent. People may use logical reasoning more easily in familiar domains while they struggle to do logically similar tasks in unfamiliar domains.

These studies highlighted a potential reason my students struggle with this geometry topic and a potential strategy for addressing this struggle. Terms like rhombus, parallelogram, and quadrilateral are not “familiar” for my students. Therefore, they struggle to determine the validity of statements such as “All rhombuses are parallelograms,” and “All parallelograms are rhombuses.”

However, my students do not struggle with logically similar statements about familiar domains. After this lecture, I asked my students about the truth of the statements, “All students in our class are students at A.S. Jenks,” and “All students at A.S. Jenks are students in our class.” They were able to quickly and easily determine that the first statement was true while the second statement was not. Even though it is a logically identical task to the statements about rhombuses and parallelograms, the domain influences how well my students use logical reasoning to determine the validity of the statements.

One potential instructional strategy to address this would be to make my students more deeply familiar with the necessary vocabulary, such as parallelogram and rhombus. If I could turn these terms into a “familiar domain” for my students, they may be more equipped to reason logically about the relationship between the terms.

In a subsequent one-on-one meeting with Dr. Richie, he suggested that I look into research about the power of analogies to help my students bridge the gap between the reasoning in familiar domains and unfamiliar domains. Using analogies can help people to map new information onto existing, familiar frameworks. Gick and Holyoak (1980) wrote about how people can solve target problems more easily when they are presented with “story analogies.” They proposed that there are three steps people take to use “story analogies” to solve an unfamiliar problem: 1) Construct a representation of the story analogy and of the target problem, 2) Map the relationship between the corresponding terms in the story analogy and in the target problem, and 3) Use the mapping relationship to translate the solution from the story analogy into a parallel solution to the target problem (p. 314 – 315).

My discussion with Dr. Richie and this article led me to think about the potential of teaching my students how to reason about quadrilaterals with clear analogies that are logically similar but about content that is more familiar to them. For instance, I could present students with the statements:

- All cats are animals (true).

- All animals are cats (false).

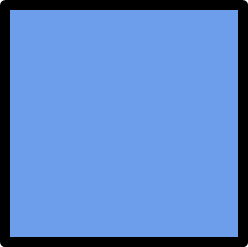

Based on Glick and Holyoak’s (1980) work, I would also provide students with a visual representation of this relationship. For example, a box within a box that shows the relationship between the two categories:

As discussed above, my students can easily understand the logic of the above statements since they relate to a familiar context. Then, I could substitute words from the geometry unit to present students with these statements and ask them to determine their validity:

- All rhombuses are parallelograms (true).

- All parallelograms are rhombuses (false).

By presenting the information this way, students would be able to use a familiar situation with an analogous structure to solve a new problem. They would be able to map the term “rhombuses” onto the familiar concept of “cats” and the term “parallelograms” onto the concept of “animals” to gain a deeper understanding of the relationship between the terms. This would help them to logically determine that the first statement is true and the second statement is false.

In the seminar session on heuristics, we also learned about the availability heuristic. When people use this “shortcut,” they judge events that are more easily remembered as more likely than events that are harder to remember (Tversky & Kahneman, 1973). For example, most people say that there are more words that start with “r” than words that have “r” as the third letter, even though three times as many words have “r” as the third letter. Since remembering words that start with “r” is easier, people judge those words as more frequent.

Learning about the availability heuristic gave me some insight into why my students struggle to identify certain quadrilaterals by all of their appropriate categories. Students are heavily exposed to terms like “rectangle” and “square” throughout their elementary education, while terms like quadrilateral, parallelogram, trapezoid, and rhombus are introduced in fourth grade. While the availability heuristic tends to address tasks that have to do with frequency and likelihood, it occurred to me that the terms “square” and “rectangle” might be more “available” in students’ memory. Therefore, when presented with a square, they can usually identify it as a square and often identify it as a rectangle as well. However, they struggle to identify it as a parallelogram, rhombus, and quadrilateral, since those terms are less “available” in their memory. This potential cause for students’ struggles once again indicated that I needed to try to immerse students into the less familiar terms of the unit so they might become just as “available” in their memory as more familiar terms.

Finally, learning about the representativeness heuristic provided more insight into why my students often struggle to identify a shape by all of its categories. The representativeness heuristic refers to the “shortcut” people take when they judge the probability of an event based on comparing it to a prototype or stereotype. This can help to speed up decisions or judgments, but can lead to illogical thinking.

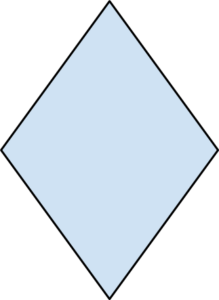

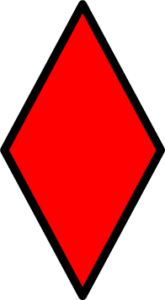

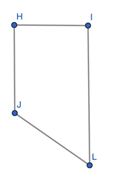

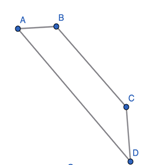

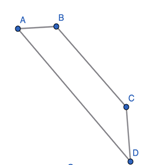

Learning about this heuristic made me wonder if students hold “prototypes” of each shape in their minds. For instance, the rhombus shape is often described as a “diamond,” so students may picture this when they think of “rhombus”:

However, the mathematical definition of a rhombus is any parallelogram with four equal sides. Therefore, this shape also meets the criteria of being a rhombus:

If students are presented with a statement such as, “The blue shape is a rhombus,” they frequently respond that the statement is false. They may be quickly comparing the shape to the prototype they have of a rhombus and determining that it does not match the prototype.

To address this, I may need to teach students about a more deliberate process for categorizing shapes. For instance, students could consider a checklist of attributes (Does it have 4 sides? Does it have opposite pairs of parallel sides? Does it have equal sides?) when classifying shapes rather than quickly jumping to their first idea. I also may need to purposely expose them to shapes that do not resemble the “prototype” for that shape and foster discussion about how the shape still meets the criteria for that category.

Part III. Categories, Concepts, and Words

Although we did not cover the topic during the TIP seminar, I was able to watch recordings of Dr. Richie’s lectures on concepts. While statement logic requires us to understand the meaning of sentences (“If it rains, I will bring an umbrella”), cognitive scientists are also interested in our understanding of the underlying concepts in a sentence (rain, umbrella, etc.). How do we understand the concept “umbrella?” How do we recognize umbrellas in the world? How do we determine whether something is or is not an umbrella?

First, cognitive scientists distinguish between categories, concepts, and words. A category is a set of things in the world that are usually regarded as having a particular shared set of characteristics. Categories may be described with a single word (cats) or with several words (things you need to go camping).

A concept is a mental construct that describes or hypothesizes about a category’s shared characteristics. Concepts do not necessarily need word labels. For instance, if you are shown images of an animal, you do not know the name of, you will still be able to make generalizations about that animal (It has pointy ears, it has furs, it has spots) and form a concept of that animal in your mind.

Once you form the mental concept of the animal, you can learn the name of the animal and label the concept with a word. Words act as labels for concepts. There is some evidence that learning a distinct name or word for an object enhances an infant’s encoding and memory of the object, indicating that the naming process is an important part of learning a concept (LaTourrette & Waxman, 2020).

I thought about how the distinctions between categories, concepts, and words may apply to my unit. In the unit, students are required to take shapes that exist in the world and sort them into categories. This task requires that they develop concepts that they label with the terms square, rectangle, rhombus, parallelogram, trapezoid and quadrilateral in their minds. Therefore, I need to understand how they develop concepts in order to help them develop complete and accurate concepts of these shapes.

The idea that we develop concepts and then label them with words also interested me. In a typical instruction model, students are presented with the terms (rhombus) and the definitions or characteristics (four equal sides) simultaneously. Perhaps it would be more helpful to show students many images that have the characteristics of a rhombus, therefore allowing them to develop the concept, before labeling that concept with a word.

Two important theories of concepts are the prototype theory of concepts and the exemplar theory of concepts. The prototype theory of concepts posits that we hold a central or idealized representation of a concept. For instance, if we consider the concept of a “bird,” we might picture a robin in our mind. Our speed and accuracy for categorizing something as a bird depends on how closely it resembles the prototypical image of a bird that we hold in our minds. We can quickly identify an oriole as a bird since it resembles the prototype, but we might need to take a moment to identify a penguin or an ostrich as a bird, since they do not resemble the prototype as closely. Studies that ask participants to list members of a category, rate examples by their level of “typicality,” verify sentences, and quickly identify whether pictures fit into a category have supported this theory. The prototype theory reminded me of the representativeness heuristic, since both ideas prompted me to think about how students hold prototypes of each shape in their head. Students’ ability to identify certain shapes may hinge on the math problem’s level of resemblance to the prototypical version of that shape that students hold in their minds.

The exemplar theory proposes that rather than constructing a single prototype for a concept, a concept consists of all of the exemplars of that concept that we have encountered. Our likelihood or speed of categorizing something as falling within a concept is proportional to the total similarity the object has to all of the exemplars we have stored.

The exemplar theory and prototype theory of concepts align with research about how young children learn shapes. The “shape bias” refers to young children’s tendency to categorize objects by shape once they learn that objects are often defined by their shape rather than by other attributes. For instance, a large, red cup and a small, blue cup are both “cups” because of their shape. While the “shape bias” helps children to learn new concepts, it can also be a hindrance when trying to teach children more refined shape concepts. Due to repeated exposure to “canonical” versions of a shape, children often do not include non-standard versions of shapes in a shape category (Verdine et al., 2016).

The ideas about prototype theory, exemplar theory, and shape bias pointed me towards a potential strategy for overcoming difficulty with the geometry concepts in this unit. I need to expose my students to varied exemplars of each shape in order to help them build more complete, accurate concepts.

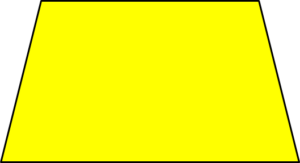

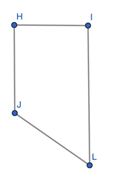

For instance, students may hold only a single exemplar of a trapezoid in their mind. The image below represents this “typical” trapezoid that they have repeatedly encountered in previous grades. It is horizontally oriented with the top and bottom sides running parallel to each other. Students often use geometry tiles that only present a trapezoid like this:

However, in fifth grade, students are expected to recognize the shapes to the right as trapezoids as well. By repeatedly and meaningfully exposing my students to these trapezoids that differ from the exemplar above, they may build their concept of a trapezoid to include more varied exemplars. This aligns with research that exposing learning to more variable input when they are learning a skill improves their ability to generalize the skill to new stimuli (Raviv et al, 2022).

However, simply seeing more varied examples of the different shapes may not be sufficient to help students to master this content. I also need to teach students that proving something in geometry is a deliberate, precise process that requires them to carefully consider various information. Challenges to the prototype theory and the exemplar theory of concepts helped me to understand how to approach this process with my students.

Armstrong et al. (1983) challenged prototype and exemplar theory by pointing out that some concepts do not have a prototype. For instance, there is no “prototypical” even or odd number. However, the same types of experiments that seemed to confirm the prototype or exemplar theory were recreated with concepts that do not have a prototype. For example, people consistently rated lower odd numbers, such as 3, as more “typical” odd numbers than higher odd numbers, such as 91. People also have faster reaction times when identifying these lower odd numbers than when they are identifying higher numbers. The fact that people have the same results with concepts that are based on a definition as they do with concepts that may be based on a prototype challenges the prototype theory and the exemplar theory of concepts.

An alternate view about concepts is that concepts are theories. This “theory theory” says that as we experience the world, we develop theories that explain how something works. Even before we are explicitly taught how things work, we develop theories about the relevant features that will help us to categorize things. For instance, over time we may develop a theory that being sick causes you to blow your nose. Therefore, when we see a person blowing their nose, we can categorize them as a sick person.

Learning about how cognitive scientists think about how we use concepts to categorize things and label them with words further emphasized to me how I need to explicitly teach students how to logically categorize quadrilaterals. Doing so will ideally ensure that students are not simply quickly comparing a shape to a “prototype” in their minds, but rather developing full, accurate theories about what makes something a rhombus or a parallelogram and then using those theories to precisely categorize shapes.

Content Objectives

As a result of my experience in the Cognitive Science seminar and my independent research, I decided to create a unit that would address my students’ difficulty with using logical reasoning to solve geometry problems, particularly problems related to classifying quadrilaterals and understanding the hierarchical relationships between different quadrilaterals.

The unit will address the following objectives:

- Students will know the definitions of the terms quadrilateral, trapezoid, parallelogram, rhombus, rectangle, square, parallel, right angle, acute angle, and obtuse angle.

- Students will adopt a process for classifying quadrilaterals that uses the properties of quadrilaterals to identify a quadrilateral by all of its appropriate categories.

- Students will use visual models and analogies to deductively reason about the hierarchical relationships between categories of quadrilaterals.

One major gap in the existing curriculum is that students are only explicitly taught the definitions of rhombuses and trapezoids, as it is assumed that they learned the definition of quadrilateral, parallelogram, squares, and rectangles in previous grades. Another gap in the existing curriculum is that while it does provide this visual model to represent the hierarchical relationships between categories of quadrilaterals, it does not provide any explicit instruction about how to use that model to logically categorize shapes or to reason about the relationships between shapes.

One major gap in the existing curriculum is that students are only explicitly taught the definitions of rhombuses and trapezoids, as it is assumed that they learned the definition of quadrilateral, parallelogram, squares, and rectangles in previous grades. Another gap in the existing curriculum is that while it does provide this visual model to represent the hierarchical relationships between categories of quadrilaterals, it does not provide any explicit instruction about how to use that model to logically categorize shapes or to reason about the relationships between shapes.