This curriculum unit is an exploration of the aspects of culture brought to this country by German-speaking groups, and specifically the Moravians. The unit is intended for use alongside a high school German language curriculum. Among other related arts, students will make traditional paper stars, paper bells, modular folded stars, and three dimensional Moravian stars. They may experience traditional Moravian foods and music. In addition, students may explore the possibilities for animating their own German stories with pop-up pages. Field trips to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania and the Moravian Archives will complement classroom activities to make the unit rich and meaningful.

This curriculum unit is an exploration of the aspects of culture brought to this country by German-speaking groups, and specifically the Moravians. Originally from the eastern part of what is now the Czech Republic, one part of a religious sect of Moravians fled first to German-speaking Saxony, and then to colonial Pennsylvania. On Christmas Eve, 1741, they founded a mission here and named the place Bethlehem. This unit is intended for use alongside a high school German language curriculum, specifically with students of The U School in mind. Among other related arts, students will make traditional paper stars, paper bells, modular folded stars, and three dimensional Moravian stars. The modular stars are known as Fröbel stars, or Fröbel-inspired stars, named after the early childhood education pioneer, Friedrich Fröbel. In addition, students may explore the possibilities for animating their own German stories with pop-up pages. Field trips will complement classroom activities to make the unit rich and meaningful. The U School is a small high school of about 350 students in the School District of Philadelphia’s Innovation Network. Admission is by lottery. The first freshman class entered in September of 2014, and this year for the first time the school has a full complement of 9th through 12th grades. There are no art or music classes per se, but there is a sophisticated digital design lab. Instruction at The U School is student-centered. Much of the coursework is project-based. All students have either a school Chromebook or bring their own device. The educational model brings together asynchronous learning, grouping by autonomy level, and restorative discipline. We therefore enjoy a rather gentle school climate. Through the cooperation of teachers and community partners, students participate in dance, mural arts, fashion design, and other arts. This unit is written with an eye to creating cross-curricular projects with mathematics and geometry classes.

The learning of a new language inevitably extends beyond just vocabulary and grammar. History and related arts quickly become a secondary focus of study, and often the lasting incentive for learning the language. To that end, the activities have been selected to appeal to as many senses as possible. In traditional western education, we tend to strip skills of their contexts and place them in narrow and discrete compartments. This unit attempts to reconstitute those skills in the context of the cultures that prized them. My German students at The U School chose German for different reasons. Some wanted the challenge of a “hard” language. Others are history buffs or video gamers who regularly come across German phrases. Still others want to explore our local landscape of cultural connections. All of them are still sorting out who the Amish, the Mennonites, and the Moravians are. So that students may explore the cultural mix of our regional heritage, we will examine Moravian documents, learn to write the archaic German script, make paper stars, and even sample traditional sweet rolls. To be sure, there is no Moravian monopoly on the folded star. A web search will turn up the same star under the names Swedish star, Danish star, German star, Nordic star, or Fröbel star. In some places, it is even called the Pennsylvania star. Across Europe and across generations, a galaxy of paper stars, as well as stars from ribbon and straw, may be found in folk arts and crafts. (Czech stars made from straw and red thread) Friedrich Fröbel, the German educator who originated the Kindergarten and whose philosophy for modern education influenced Maria Montessori, among others, incorporated paper folding in his early childhood instruction in order to instill mathematics concepts. Though he most certainly did not invent the German star, Fröbel employed common hand crafts of the day to help children develop motor skills, make cross-curricular connections, and exercise creativity of design, with the result that Fröbel-inspired paper stars are now ubiquitous. Like Fröbel, our own PA state standards call for paper folding for children as early as Pre-K. While some of the students in my German classes may have experience with paper folding, all of them have been happy to discover or rediscover the craft as we worked through these activities with them this spring. While the skills do not support language acquisition directly, they fall squarely in the Pennsylvania state standards for World Language levels I and II, and allow students to make sense of the world from a new perspective. For this reason, I am happy to devote class time to these related arts, since the skills are transferable to other areas of study. With planning, it will be possible to establish cross-curricular connections with my colleagues in STEaM.

Probably the most recognizable community of German-speaking immigrants in our region are the Pennsylvania Dutch, or Pennsylvania Germans. The appellation “Dutch” refers to the German language, “Deutsch,” that they speak. While I would be happy to have my students study the culture and history of our neighbors in Lancaster county, my choice to direct our attention north to Bethlehem is based on the quality of resources available at the Moravian Archives and the variety of German used by the Moravians, which, while it is not modern high German, is nevertheless close to our textbook German. Moravian culture has been known for progressive views of education since the time of Bishop John Amos Comenius (1592-1670). None of the Moravian culture derives from the pedagogical work of Friedrich Fröbel, as Fröbel was born after the first Moravian immigrants came to North America. Yet various groups of immigrants drew from the same sources as Fröbel, and the folk arts ubiquitous across Europe arrived on our continent during that era as a select remix. The same recipes, games, songs, and crafts that Moravian families cherished were gathered and systematized by Fröbel and other educators, and brought to this continent in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. What is interesting is the pedagogical warrant we teachers receive from the foundations laid by Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi, Friedrich Fröbel, Maria Montessori, and others. A predecessor of Friedrich Fröbel, Heinrich Pestalozzi was a Swiss educator and entrepreneur whose revolutionary approach to early childhood education set aside punishment and compulsion, relying instead on the child’s own impetus to seek new experiences. Like The U School, where I teach, Pestalozzi’s schools had no special requirements for admission—a policy unique in its time—and emphasized student autonomy and agency. All instruction was child-centered. Teachers stood ready to supply materials on demand, and pupils were afforded plenty of time and space to innovate, reflect, and revise. It is not hard to appreciate Fröbel’s attraction to Pestalozzi’s model. Friedrich Fröbel’s childhood and youth had been fraught with turmoil. Following the death of his mother in 1783, when he was just an infant, Fröbel’s uncle took him in and provided for his education, including an apprenticeship in forestry. Fröbel’s father died in 1802. After an unsuccessful stint at the University of Jena and a short list of odd jobs, Fröbel finally secured a position as a teacher at the Model School (Musterschule) in Frankfurt. It was here that he was first introduced to Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi’s philosophy of education, and in the process found his calling. He was determined to create a gentle, rich and meaningful childhood education model, and set about to make that education available to young children from all levels of society. Fröbel never managed to finish a university degree, or establish credentials, but he continued to study and teach, traveling to Switzerland to study with Heinrich Pestalozzi’s school, and eventually developing an articulated method of early childhood education all his own, complete with graded sets of rudimentary manipulatives (Spielgaben). This highly effective system for teaching children about nature, the arts, and mathematics Fröbel named Kindergarten. Similar principles of early childhood education were taken up and codified in Rudolf Steiner’s Waldorf School model, and by Maria Montessori’s renowned Montessori method. Even a preschool that does not follow the Montessori method to the letter may incorporate key aspects of the Montessori approach. Her notion of school work, like Fröbel’s, called into question the “prevailing assumptions about the nature of childhood, the roles of teachers, and the purpose of schooling” in much the same way as schools in the Innovation Network of the School District of Philadelphia, and in particular at The U School.

The delight and frustration of this unit is that there is no end to the creative possibility. It’s not that the goals are ill-defined. It’s just that history, mathematics, language, and the related arts all tie in, and all spin out to tantalizing tangents, as it always is when we study cultures. The main point is to discover what life is/was like for another group of people in a different time and/or place, by experiencing what they have enjoyed, with as many of our senses as possible. For the sake of order, I limited our objectives. Drawing from Pennsylvania state standards and the Year at a Glance details for World Language I and II, these are our culminating performance assessments: Any other avenue of inquiry that my students pursue is a bonus. For example, this spring we came up with the following questions:

At The U School, students earn credit by demonstrating what they have learned. We know we have acquired a competency when we can perform a skill, or better yet, when we can teach it to others. In addition to presentational speaking and persuasive writing, students create infographics, slide presentations, dramas, monologues, and other evidence of learning. All of these activities become rich and meaningful, exceeding the parameters of my rubrics, when students take up a base model, evaluate and revise their work, and reformulate the project, finally making their own original creation. At a minimum, students will be able to produce the projects on their own or in collaboration. They will also master the English vocabulary necessary to have a descriptive command of what they have accomplished. While it is certainly a valid learning experience to engage in these activities solely for enrichment, having participated in all the activities, students will prepare a demonstration of one aspect of what they discover—one craft, one recipe, one song, or one story—and teach it to the class for a grade. Key tasks will be to master folding skills through practice, and then to bake, write, design, or compose original work, and finally to reflect on the meaning of community for the target culture. Use a think-pair-share strategy with questions for reflection to hear their speculations. The students’ thought processes are made visible as they predict outcomes, experiment with recipes, compose original music and literature, and design new star configurations. The paper folding activities are arranged in increasing rigor to allow scaffolding of tasks, and to strengthen student perseverance. All lessons invite the student to complete a finished product, allowing curriculum to be delivered in a mode of hands-on discovery. Students are asked to take a concept one step further and come up with their own version of a model, fostering creativity, innovation, and risk-taking. Failures will be celebrated as an opportunity for trouble-shooting. Pastry recipes and folding instructions alike involve multi-step procedures, and all activities may be arranged on a choice board. Finally, integrate technology with instruction and assessment wherever possible. A choice board and a bulletin board display of final projects are great classroom fixtures. Technology adds yet another layer, integrating skills that students are acquiring in other classes. For instruction, use videos as homework in order to flip the classroom, maximizing class time. In class, demonstrate the steps to completing a task using a document camera. For assessment, have students record their songs on GarageBand or Audacity, both free. They may then add tracks and mix their sound. Have students photograph their classmates’ work, crop and adjust the images, and create a photo montage. Be sure they send their favorite images to the coordinator of the school website with a caption or an article. Have a student recruit a sous chef and a videographer and produce a cooking video showcasing a sweet bun recipe with variations. Have students make videos of their paper folding project, complete with captions, video overlay and a full sound track. Use free CAD software, like Inkscape, to bridge student learning to the STEaM fields, then have a student teach the technology or produce a tutorial.

German bells are commonly folded from squares, but they may also be made from triangles and pentagons. Traditionally, the bells are made from colored paper, hung from ribbons, and used as decorations. A bell may also be used as a gift box, especially when decorated or when made with wrapping paper. In preparation for this lesson, you will need scissors and bell templates. Print enough polygons for each student to have one triangle, one square, and one pentagon. Colored paper, wrapping paper, or cardstock are optional, as well as ribbon, yarn, or wire. Print out other kinds of polygons, and set them aside for students who finish early. You can make large equilateral polygons on Word using the shapes function and the shift key. Hold down the shift key when you resize any shape, and it will keep its aspect ratio. Or, if you have lots of class time and a sense of humor, forego the shift key and make polygons with skewed aspect ratios! One 47-minute class period is enough time for each student to make up to three bells. A good description of German bells, complete with patterns, can be found in William A. Miller’s article, “German Bells.” Miller poses the following questions for students: I would add: Here are instructions for the German bells, in case you do not have access to the article. The instructions will be the same for any polygon you use. My students are sure that bells cannot be made from other polygons. Intentionally I withheld that information so that they would spend some extra time testing their various hunches. We also found that the templates in the article were not symmetrical. The three equilateral polygons we used are therefore available in the appendix below. German bells from equilateral square, pentagon, and triangle The common folded Moravian star is a modular star made from four long strips of quilling paper. Unlike many modular stars and medallions, the Moravian star is three-dimensional as opposed to flat-fold. Eight of the points do not get flattened. Any size star is possible, so long as the length of the paper approaches thirty times the width. We used ¾ inch quilling paper. After standing for hours at the paper cutter, trying to get the strips even, I was glad to find a vendor for the quilling paper, and their colors are beautiful. I found the largest collection of modular stars in the book, Folded Paper German Stars, by Armin Täubner. The book is a direct translation of the German volume, Das große Fröbelbuch. Follow the instructions for the Fröbel star starting on page 68. Fröbel stars and quilling paper Materials needed: Most students will find this project challenging, so allow plenty of time for false starts, and have extra paper on hand. It is a good idea to pass out an instruction sheet, in addition to showing the video, because while students will need to see the motion of each step, they will want to have the security of instructions in hand. Be ready to pause the video. Have students work in groups or in pairs for encouragement. Traditionally, these paper stars were dipped in wax and sprinkled with glitter. Waxed stars may be hung outside, and will hold up in wet weather. For the classroom, it might be fun to try glue and glitter or spray glitter. It is also possible to make a modular ball from six modular stars arranged like the six faces of dice. Questions for reflection: Farther Afield If you never attempt the polyhedral stars in the next section, I don’t blame you. Instead of raising the difficulty of your next activity, consider branching out. Try some of the other modular stars in Täubner’s book. Happily, they are no more difficult than the star you just tried, and they have a great many variations. A single medallion can be used as a candle holder (p. 7). A series of flat-folds can be strung in a garland (p. 20). In other cases, six or twelve medallions can be joined into spheres (p.44). These last two projects are ideal for collaborative work, as students who work at different paces can all keep busy together. The modular star is not exclusively Moravian. Nor is it the first shape that comes to mind when I think of Moravian stars. The quintessential Moravian star is something else altogether. Run an image search, and you will find three-dimensional stars of six points or many more, always an even number, usually symmetrical, and based on polyhedra. The book, How to Make Moravian Stars, comes with patterns for six different polyhedral stars, as well instructions for designing additional stars. The simplest star in the set, a North Star, has six points. There is also an eight-point star with triangular points, a twelve-point star with pentagonal points, a twenty-point with triangular points, a 26-point star, the Traditional Moravian Star, and a 26-point Star of Bethlehem with an elongated point at the bottom. In lieu of the book, there are free .pdf instructions available online. Whatever you choose, print the pattern pages on cardstock. And whatever pattern you decide on, try it ahead of time, and have an example for students to examine in their hands. This is a good collaborative activity, as students will need help holding the pieces together. I would recommend that one star be assembled by one group or pair of students. Depending on the complexity of the star you choose, this project could easily take three class periods to complete—but it will be worth it! Materials needed: Even Farther Afield There are a number of interesting paper folding activities that are less daunting for school students than modular stars, and which lend themselves to cross-curricular study—letter locking and pop-up pages, for example. Locked letters are not just for passing note in class. A student may wish to research correspondence between historical figures. If the postal system at the time had no presumption of privacy, there is a good chance the archival papers will show evidence of letter locking. Some German locked letters are extant, but also many more in Italian. For example, the letters from Galileo Galilei to his daughter Maria Celeste are long gone, but hers to him are preserved. You can still see the folds, what appear to be the remains of sealing wax, and occasionally, cuts and scraps of what may have been locks. Look for a telltale triangular piece, or a missing corner of a page. Have students try a letter locking technique. Check at the historical Society of Pennsylvania and at the Moravian Archives for locked letters in the holdings. My students were very productive when making pop-up pages, even if they got a little carried away. Having already written silly little stories in German, students spent time constructing books and illustrating them with pop-up mechanisms. The richest source of pop-up tutorials we found came from Duncan Birmingham. Birmingham has posted over forty videos on his YouTube channel, most of them tutorials. If students have access to computers, it is enough to give a short introduction to a simple pull-tab or V-fold, and then give students paper, scissors, glue, and time to complete their projects. Another tradition that is characteristically Moravian is the Moravian love feast. Moravians base the practice on the agape meals of the early church as described in the Bible, but it is not a sacrament, and should not be confused with Communion. The communal meal demonstrates the Moravian motto: In essentials unity, in non-essentials liberty, and in all things love.” As a practice of the congregation, the love feast fosters goodwill among members, and it will often be celebrated before contentious church business meetings. The “meal” is sometimes held in the sanctuary. While the congregation sings hymns, sweet rolls and milky tea or hot chocolate are served by fellow members. This activity will take less than a class period, and it can be paired with the making of the first German bells. Show the video on the Moravian love feast. Serve sweet buns and hot chocolate. The first time I present a love feast, I come to the desk or table and serve each student. First model the activity in this way. A week later, have students prepare a love feast of buns and chocolate using recipes they find or create, and have students serve each other. When I prepare a love feast, I sometimes use my mother’s recipe for potato bread rolls or cinnamon buns. Use a recipe that is meaningful to you, or an authentic Moravian recipe. I like to use a recipe from the Moravian region of North Carolina. On occasion recipes fail, or there’s no time to bake; in a pinch, substitute Krispy Kreme cinnamon buns. I stress the use of homemade buns or the best store-bought alternative because this activity is not a snack. It’s really an opportunity to afford each other dignity, in the context of a lesson where we observe the Moravian practice of demonstrating care for the wellbeing of all people in the community. Use good quality hot chocolate mix like Ghirardelli double chocolate made with whole milk, or nice quality chocolate milk (e.g. Baily’s Dairy) warmed in a crock pot. Use real mugs and real plates and cloth napkins, if possible. Questions for reflection and further study:Beginning-level Folding Activity – German Bells

7. Glue two adjacent spikes together. If possible, staple the inside flaps to keep the glue from failing.

9. Gently shape and straighten the sides. The interesting folds in the base, and the zig-zag folds around the girth of the polyhedron will need your help. The glue doesn’t always hold well, so you may want to use a loose rubber band around the tip while the glue dries.

10. Ta-daa! You have a German bell! If you like, poke a hole in the base and run string/ribbon/wire through it. Add a tassel and a loop, and it’s ready for display.Intermediate-level Folding Activity – “Fröbel” or “Moravian” Stars (Modular Stars)

quilling paper, four strips per star

paper instructions

projecting equipment and a video

optional glue, glitter, or spray glitter

Advanced Folding Activity – “Bethlehem” or “Moravian” Stars (Polyhedral Stars)

Sweet Buns and Hot Chocolate

[Please see PDF attached above for additional resources]

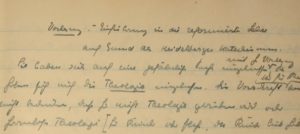

On the one hand, field trips can be quite cost-prohibitive for our students. There is simply no budget for bus transportation. On the other hand, most of the students at The U School are issued a SEPTA Transpass, making a trip within the city affordable. The second-best source of historical documents in German in the area is located in The Historical Society of Pennsylvania, at 300 Locust Street (215-732-6200). Students can begin preliminary investigations online. Then with preparation ahead of time, classes or groups can examine primary source documents at the HSP with the help of HSP education staff. On the HSP web site, students may run a search for any of the following terms, or choose their own: German, Moravian, Sütterlin, Bethlehem, Mennonite, Herrnhuter, Bohemia, Hutterites, Amish, Brethren, Zinzendorf Student instructions for documenting the findings: Tell the title, date, author, language, place of origin, and genre of the document. In a separate section, list avenues of inquiry, writing down the specific questions (for the HSP staff) that need to be addressed for clarity on the document itself, or for understanding its context and implications. Before the class visits the HSP, identify the documents to see, and notify the education staff so that they can pull them in advance and place them in sleeves for you, if necessary. If possible, ask for high quality scans of any manuscript pages, and place them in page protectors. Finally, have students plan a strategy for using their findings as part of a cross-curricular project. By far the richest source of Moravian literature in our region is housed at the Moravian Archives in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. An archive differs from a library primarily in that archival holdings are often unique documents, many of which have a backstory of their own. An archive will also house works of art, paintings, photographs, and even furniture and personal effects of historic figures, all of which help tell a story. Many of the books and documents at the Moravian Archives are hand-written in a beautiful but archaic longhand script. It takes some practice, but it is possible to learn to decipher old German scripts. Students who attend both a session at school and at the archives will learn to form the upper case and lower case letters. In time they may help sustain a dying art and discover a professional niche. The Archives are situated on the campus of Moravian College, making a field trip to Bethlehem a double opportunity for high school students. This spring I was able to secure a mini-grant for bus transportation to Bethlehem. Since my German class barely filled half the bus, I opened up the field trip to any student interested in a campus visit to Moravian College. Our school counselor co-chaperoned, we conducted two field trips in one, and the day was a great success. This is a trip I would do year after year. The Moravian Archives staff are really flexible with their resources. They place a high priority of educational outreach. It is possible to have an archivist come to the school and conduct an educational session. It is also possible to visit the archives, have a class on German scripts, practice writing with quill pens and ink bottles, and tour the vault. We did both. The suggested donation was $50, which covers the cost of quills, ink, handouts, and high resolution scans of primary source documents. We arranged for the assistant archivist to come to our school and teach a session in our classroom. He gave background on the Moravian community in Pennsylvania in general, and then gave instruction on the lower case letters (in pencil) of the archaic German script used in the eighteenth century and up until the early twentieth century. Having learned about the Moravian love feast, we used some of the time to enjoy cinnamon buns and hot chocolate. Then, a week later, we loaded onto a yellow bus and made the trip to Bethlehem to visit the Archive. I’m really pleased with the arrangement. My students already knew a little about what they were going to see, and they already knew the archivist who was going to greet them in Bethlehem. The group engaged readily with the topics and were really happy to see our archivist again. In the Archive, students sat around conference tables and learned the upper case letters. Then they put it all together and wrote in German script with quill pens! Finally they were able to see the volumes of hand written documents produced by the Moravian communities. The group had a tour of the vault, and asked dozens of questions. The archivist was happy to pull items off the shelves and let students poke around. Several times he mentioned career opportunities in his field. He talked about his career progression and his commitment to being a life-long learner, not having much German coursework before he started this job, and encouraged the young people to continue their German studies. Again, I would really recommend having two separate experiences a week apart. The arrangement allows for a little more depth into the material and a better connection for these students who are having an extraordinarily rare experience. I would also, as mentioned, take the opportunity to incorporate a college tour into the field trip. Our school counselor had high praise for the campus tour and the college offerings. Durham School Services (215-537-5405) was the only bus company on the School District of Philadelphia’s list of approved transportation services that could accommodate our schedule and budget. We had a very good experience with Durham. (A sample of German scripts from the 1930s)The Historical Society of Pennsylvania

The Moravian Archives

Here are listed standards that apply mainly to cultural knowledge. Some of these standards are related to language acquisition. There are possibly even more relevant language acquisition standards, depending on how a teacher may choose to implement the curriculum unit. The following World Language standards from the Standards Aligned System (SAS), developed by the Pennsylvania Department of Education, may be addressed in this unit: Standard – 12.1.1.S1.E Find words used in magazines, commercials and advertisements influenced by the target language. Standard – 12.1.1.S2.F Model and represent the cross-curriculum connections in other subject areas for classmates and language teacher through the target language. Standard – 12.1.1.S4.E Select a specific historical event that occurred in the target language/culture and the English/American culture. Demonstrate comparisons and/or contrasts of how target language vocabulary is used in describing the bicultural event. Standard – 12.1.S1.E Identify words from the target language that are commonly used in English. Standard – 12.1.S4.E Describe the influence of historical events in the target culture/language that have an impact on the English language and culture. Standard – 12.1.S4.F Research, analyze and describe the target language’s influence in different areas of the school curriculum. Standard – 12.5.1.S1.D Use speaking, writing and reading to compare and connect the uses of English with the target language spoken in the local, national and global communities. Standards – 12.5.1.S2.A, 12.5.1.S2.B Use target language skills to communicate interactively for practical purposes and for personal enjoyment of the resources in the local community. Standard – 12.5.1.S2.C Use target language skills to communicate interactively for practical purposes and for personal enjoyment in the global community. Standard – 12.5.1.S2.D Use speaking, writing and reading to compare and connect local, national and global resources in English speaking communities with the target language resources in those communities. Standards – 12.5.1.S3.A, 12.5.1.S3.B, 12.5.1.S3.C Name local employment areas in which language skills may be used. Use the language at the necessary language proficiency level to interact with local community members in their occupations. Standard – 12.5.1.S3.D Use speaking, writing and reading to compare and connect local, national and global employment opportunities for those who speak English and those who speak English and a target language. Standards – 12.5.1.S4.A, 12.5.1.S4.B, 12.5.1.S4.C Research, select and use local authentic materials to determine career opportunities, enrichment activities and personal enjoyment. Standard – 12.5.1.S4.D Use speaking, writing and reading to compare and connect available opportunities in the local, national and global English speaking communities with the target language opportunities to continue involvement for lifelong learning and personal enjoyment. Standard – 12.5.S1.A Know where in the local and regional community the target language and culture are useful Standard – 12.5.S1.B Know where in the national community the target language and culture are experienced. Standard – 12.5.S1.C Know where the target language is spoken in the global community. Standard – 12.5.S1.D Know simple comparisons and connections that can be made between the target language and English in the local, national and global communities. Standards – 12.5.S2.A, 12.5.S2.B, 12.5.S2.C Identify local resources for gathering information for practical purposes and for personal enjoyment. Standard – 12.5.S2.D Identify comparisons and connections about resources in the local, national and global communities where the target language is used and resources where English is spoken or written in those same communities. Standards – 12.5.S3.A, 12.5.S3.B, 12.5.S3.C Identify employment areas in the local community where the target language is used and how and why the target language is necessary. Standard – 12.5.S3.D Explain comparisons and connections for employment opportunities that can be made in the local, national and global English-speaking communities with Standards – 12.5.S4.A, 12.5.S4.B, 12.5.S4.C Assess available opportunities in the local community to continue involvement with the target culture for lifelong learning and personal enjoyment. Standard – 12.5.S4.D Assess comparisons and connections of available opportunities in the local, national and global English-speaking communities to continue involvement with the target language for lifelong learning and personal enjoyment.

those who speak a target language.