Author: Keysiah M. Middleton

School/Organization:

William C. Longstreth Public School

Year: 2014

Seminar: Native American Voices: The People – Here and Now

Grade Level: 7

Keywords: Abraham, African American History, Alachua chief, American History, Andrew Jackson, Asi Yahola, Battle at Hatcheelustee Creek, Battle at Jupiter Inlet, Battle of Lockahatchee, Battle of Okeechobee, Battle of Wahoo Swamp, Ben Bruner, Black Seminoles, Coacoochee, Colonial Florida, Dade’s Massacre, Destruction of St. John’s Sugar Plantations, Duncan Clinch, Edmund P. Gaines, First Battle of Withlacoochee, Francis L. Dade, freedom fighters, Geechee, Gullah, History, John Caesar, John Horse, La Florida, Luis Fatio Pacheco, Micanopy, Micconuppe, Mikasuki, Native American History, Negro Fort Massacre, Osceola, runaway slaves, Second Battle of Withlacoochee, Seige of Camp Izard, Seminole maroons, Seminoles, St. Augustine, St. John Slave Revolt, Thomas Sidney Jesup, Tuskegee, Wild Cat, Zachary Taylor

School Subject(s): African American History, American History

“The Seminole and African Collaboration: An Alliance for Survival” is an interdisciplinary curriculum unit for upper middle and high school students that offers a perspective and details often omitted from textbooks surrounding the union of the Seminoles and Gullah (Lowcountry people of African ancestry). The unit is designed to give students an enhanced understanding of the relationships between indigenous peoples of North America and the Africans they encountered in the Southeastern region of the colonial United States. Classroom lessons examine the union between the two groups and the ways in which their partnerships affected American history utilizing engaging cooperative group activities, video technology and primary source analysis. The unit gives students the opportunity to delve into the lives of the great Seminole leaders and their chief commanders of African descent, the cultural exchanges that occurred between the two groups, and the causes for their collaboration and their military and agricultural alliances. Students will examine how this cooperation within the context of war enabled black and Native peoples to strategically challenge and resist their oppressors. Students will engage in Socratic Circle dialogue that will allow them to analyze questions such as : What is an alliance? Why are alliances created? Who do we choose to align ourselves with? Why do we dissolve our alliances? Who benefits from alliances? and How are alliances negotiated? Additionally, the unit will serve as a tool to get students thinking about- “What is rebellion?” and will open up discussion about the ways in which alliances affect our communities, governments and international affairs. A culminating exercise will assess student understanding of the alliances that ultimately created a distinctive category of freedom fighters – the Black Seminoles.

Download Unit: Middleton-Keysiah-unit.pdf

Did you try this unit in your classroom? Give us your feedback here.

Studies of indigenous Americans commonly focus on the struggle to maintain their homelands, their wars with the Spaniards, British, French, and American colonists, their dispossession of land, forced removals and migrations into “Indian Territory,” The Five Civilized Tribes, the state of Native American reservations and, more recently, questions of who has a right to Native American citizenship. However, the intimate coexistence between the Seminoles and Africans has not been explicitly addressed in our history curriculums or textbooks for our students, at any grade level. The association between the two groups during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries played a pivotal role in the various events surrounding the future of the institution of the American slavocracy and confiscation of North American land from its original inhabitants and created multiple fraudulent treaties and legislative policies that addressed the issue of slavery. Thus, “two parallel institutions joined to create Black Indians: the seizure and mistreatment of Indians and their lands and the enslavement of Africans. In their conquest of the New World, Europeans were determined to use both dark peoples.”[1] In an attempt to preserve their once strong union, the Seminoles and Africans were determined to prevent this from becoming a reality. With all their will and might, along with some cunning, coaxing, and negotiations, both dark peoples forged an alliance and fought fiercely together, for as long as time permitted, to prevent the Europeans from exploiting and destroying them. To understand the collaboration of these two distinctive groups during the colonial period is to understand the backgrounds of the Seminole natives and the Africans that they came into contact with and the circumstances that brought the two together. “Out of the fusion of these various refugee peoples of American and African descent emerged what we have come to understand as the Seminole identity.”[2] Their alliances go as far back as the history of the Spanish colonization in the New World. “Two hundred and fifty years after Juan Ponce de Leon first claimed La Florida for the Spanish crown in 1513, the native societies of coastal South Carolina and Georgia and all of Florida had disappeared. Cusabo, Guale, Apalachee, Timucuans, Calusa, Tequesta- none of these peoples were able to survive in the face of Spanish, French, and English efforts to colonize the New World. Disease and warfare reduced their populations beyond ability of survivors to accommodate the European presence and maintain ethnic identity.”[3] These natives were the ancestors of the people that eventually formed the Seminole Nation since the “Seminole Indians were themselves remnants of aboriginal groups (including Timucua, Apalachee, Oconee, and Yuchis) who fled into the swamplands of Florida.”[4] In fact, Littlefield, goes on to state that “from the Revolutionary War until 1823, the Seminoles were considered a loosely affiliated arm of the Creek Nation. During that period, however, the two groups grew farther apart in their social development and in their attitudes towards the United States. One of the points of greatest disparity concerned close relations with their blacks. When Red Stick Creeks fled to the Seminoles in 1814, a wedge was driven between the two tribes, and the gap was ever widened.”[5] Therefore, “these Indians were runaways themselves, refugees from war and oppression, exiles in a strange land,”[6] seeking asylum, freedom, their own lands, and to just be left alone. “The Seminoles of eighteenth and nineteenth-century Florida had not originated there but came in a series of migrations, which lasted more than a century. They had moved into Florida……and settled on abandoned lands of the earlier inhabitants.”[7] Covington documents the migration of the Seminoles into Florida in three distinctive phases; the first migration, he states occurred between 1702 and ended in 1750. The second migration took place between 1750 and 1812, with the third and final migration taking place from 1812 until 1820.[8] This particular migration is of great importance since it involved the migration of Cowkeeper, the founder of the Seminole Nation, and the Oconee people into the Alachua region of Florida. “Well established there by 1750, it became the nucleus of the principal Seminole tribe, the Alachua band.”[9] The separation of the Creeks and Seminoles took some time to occur. “Creek individuals, families, groups, and perhaps small towns began moving from Georgia and Alabama south into north Florida after they and the English had destroyed the aborigines and limited the area of Spanish control to the immediate environs of Saint Augustine,”[10] so that “by the end of Andrew Jackson’s Florida campaign in 1818, they had made a complete separation.”[11] Additionally, to support this, Sturtevant argues that “the deerskin trade, the introduction of guns and the increase of warfare all encouraged increased mobility and the breakup of the old settled agricultural villages.”[12] “The accession of the Red Stick refugees, Creek collaboration on the American side of the First Seminole War, and the eastward and southward movements of the Seminole settlements combined to establish firmly Seminole independence from the Creek Confederacy.”[13] The natives that broke away from the Creeks were later divided into Lower and Upper Creeks. Specific geographical locations attribute to the usage of these referential terms; for the natives did not know to nor did they address one another by these terms. Each group was referred to according to their aboriginal name. The two bands were constantly at odds with one another. The Upper Creeks were also known as Red Sticks, for they used red sticks whenever in battle. In “1813-14, slavery was one of the issues dividing Creeks in the civil conflict known as the Redstick War. After their defeat, Creek dissidents, or Redsticks, fled from their enemies into Florida, where they took refuge with the Seminoles. This violent war marks a turning point in the history of the Creeks and Seminoles as well as of the Deep South Interior.”[14] The Lower Creeks also sought refuge from the Europeans who made slaves of them and used brutal tactics to dispossess them of their hunting grounds. The Creek labeling of the indigenous peoples comes from the English. “Englishmen in the southern colonies began to use it in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.”[15] The Upper Creeks resided in the northern parts of Florida, while the Lower Creeks tended to hunt in the southern region of Florida. “English traders began to call Muskogees on the Chattahoochee “Lower Creeks” and those on the Coosa and Tallapoosa above the forks of the Alabama River “Upper Creeks.”[16] Although, Lower Creeks and Upper Creeks were constantly at war with one another, the two at some point did settle together. Littlefield writes that, “the bands of Lower and Upper Creeks, along with small groups of Yuchis and others, comprised what was popularly known as the Seminole tribe. Nearly all of the tribes, the Yuchi being a notable exception, were of the Muskogean family, speaking Muskogee or Hitchiti, and all were Creek in cultural background.”[17] It is at this juncture that it is necessary to introduce Twyman’s opposing arguments of how the Seminoles came into existence. His research gives way to a major discrepancy because most of the research on “The Seminoles and Africans” documents the Seminoles as an offshoot of the Creek Nation. Twyman states that ‘there are generally two perspectives on the origin of the Seminoles. The first perspective can be termed “mono-genesis,” and the second “poly-genesis.” The mono-genesis view is more popular. According to this view, the Seminoles are essentially an amalgam of the Creek Confederation, which migrated from Georgia into Florida and incorporated remnants of the early extinct Florida natives. The Seminoles are seen as originating about the time of the British occupation. The African presence is explained as either runaway slaves permitted to settle or as Seminoles’ slaves, who were brought or captured from white settlers.’[18] This view seems likely because it is possible for individuals that are apart of a group to disagree, depart the group and form their own new autonomous group. The information that I have previously laid out regarding the Seminoles discusses this mono-genesis view. However, Twyman states “those who accept mono-genesis are forced to ignore an existing military relationship between the non –Creek Native Americans and the Africans from British colonies, which had existed for several generations.”[19] It is not possible for history to ignore the military alliances created by the Seminoles and Africans of the Southeast region. The alliance must be recognized as a partnership that made them a significant force against the colonial United States government to be reckoned with. Their relationship was not only essential to treaty negotiations that occurred between the Seminoles and the American government, but also relevant to America since many of the treaties included clauses regarding slavery and the return of African runaways. “Even before the Washington administration, the Continental Congress had stipulations in treaties with at least 13 native peoples for the return of escape slaves.”[20] Twyman’s alternative argument states that ‘The second and less popular perspective ascribes to a poly-genesis view. According, to this view, the first Seminoles were Africans and Native Americans who fled to Florida to escape British slavery in South Carolina. From this perspective, it is asserted that the migration of Africans and Yamasees and Apalachees (both said to be branches of the Creek Confederation) began in the 1680s.’[21] The poly-genesis view also seems plausible, not to mention much more accurate based on the fact “that Africans and Americans have been interacting in a variety of settings for at least five hundred years.”[22] Because Native Americans were indigenous to North America prior to European invasions, Forbes uses “the term American for Indians in the colonial era.”[23] My contention is that this lengthy interaction among the two groups would strongly support and contribute to the cohesiveness of the military alliances forged between them from 1800 to 1860. Students will assess how these two perspectives are reconciled to determine if it is possible for both arguments to be accurate or if they may have occurred at different times. However, for all intents and purposes, this unit will follow the mono-genesis view. This view has been well researched and documented in detail. Student lessons and activities will allow for more detailed research of the opposing arguments. The Seminole were not called “Seminole” when they arrived in Florida because they were still considered Creek or by another aboriginal name. “The Exiles were by the Creek called “Seminoles,” which in their dialect signifies “runaways,” and the term being frequently used while conversing with the Indians, came into almost constant practice among the whites; and although it has now come to be applied to a certain tribe of Indians, yet it was originally used in reference to these Exiles long before the Seminole Indians had separated from the Creeks.”[24] The indigenous population had extensive contact with the Spaniards in Spanish Florida prior to and during the colonial period. It is also said that the term “Seminole” is said to be a corrupted version of the Spanish word cimarron meaning “wild” or “runaway.” Seminole is a variation of the Muskogee word “simano-li” also meaning “wild.” The Creeks gave the newly departed members the new name as a result of their gradual withdrawal and prolonged isolation from the Creek Confederation. Wright goes on to discuss the similarities of both terms- Seminole and cimarron- and how it may be possible that one word may have produced the other. He explains that there is no “R” in Hitchiti or in any of the Muskhogean languages. “R” became “l” and “cimarron” became “cimallon”- in time “Simallone” and “Seminole.”[25] This research on the origins and meaning of the term Seminole may have referred to the blacks that coexisted among the natives since the British spelled “cimmaron” as “symeron” during Drake’s 1572 voyage and……there was no change in meaning. Twyman believes there is an etymological link between “Seminole” and “cimmaron,” that scholars of the mono-genesis view argue that Seminole is derived from “cimmaron” and that it does not refer “to runaway slaves, but to Creek migrants from Florida who broke away from the Creek confederacy.” He concludes that “because the term “Seminole” was originated during the British occupation, an English word could have been used if the word was intended to refer only to Creek migrants.”[26] This offers another opportunity for student debate. Was the term Seminole originally used to refer to the Africans or Americans or both? This segues into the Africans that came into contact with Creek descendants in Florida. They too, were runaways from slavery in the British colonies. This serves as tangible proof that “resistance to enslavement took place almost immediately by the relatively powerless African peoples in the Americas, more often than not in cooperation with American Indians (Landers, 1988). The black (and Indian) cimarron communities that were found in the colonial times throughout the Spanish Caribbean……came to Florida in the mid-sixteenth century.”[27] When the Underground Railroad is mentioned, one may think of someone fleeing to the North. However, Africans in South Carolina and Georgia were fleeing south to take advantage of the Spanish crown’s proffer of freedom in La Florida. Some historians argue that it was not an Underground Railroad because Africans remained in bondage, only under Spanish rule as opposed to British. However, the Africans “were frequently aided in their escapes by Indians.”[28] These Africans were known as the Gullah-Geechee people. The names Gullah and Geechee are synonymous terms used to describe the people who are the direct descendants of the Africans who were taken from the Sierra Leonian, Liberian, and Guinea regions of West Africa during the Atlantic slave trade of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Africans from these regions often called the “Rice Coast,” “Winward Coast,” and “The Senegambia or Gambia” were experts in the industry of rice cultivation. These Africans brought with them, on European slavers, the cultivar and technology that would transform the swamps of South Carolina into very prosperous rice plantations. As a result, the Gullah-Geechee resided primarily in South Carolina and Georgia, areas also known as the Lowcountry. Proof of the Gullah-Geechee slaves’ ethnicity has been noted in historian, Joseph A. Opala,’s essay, “The Gullah: Rice, Slavery and Sierra Leone-American Connection” where he indicates that “in 1978, Dr. Ian Hancock discovered that elders among the Texas Scouts still speak a dialect of Gullah- 140 years after their ancestors were exiled from Florida and as much as 200 years after their early ancestors escaped from rice plantations in South Carolina and Georgia.”[29] It was also revealed in this essay that “in 1980, this writer found that elderly people among the Oklahoma Seminole Freedmen also speak Gullah.”[30] To further support Opala’s claim, Alicone, M. Amos in her paper, “Black Seminoles-The Gullah Connection,” asserts that in a letter to linguist Lilith M. Haynes, historian Kenneth W. Porter “admitted that Seminole Negro English……does certainly have Gullah elements.”[31] Amos shows that “Ian Hancock, the linguist who finally identified that the language spoken by them was an older form of Gullah, which he eventually named Afro-Seminole Creole.”[32] Finally, Amos also identifies various words from the Gullah vocabulary and the naming patterns that have been incorporated into the daily lives of the Black Seminole descendants of Brackettville, Texas and in Oklahoma, and notes their striking similarities. The Africans were escaping slaveholders located predominantly in South Carolina and later, in Georgia after that State was added to the Union in 1732. Information tended to circulate rapidly within the slaveholding communities because “enslaved Africans in the British colony of South Carolina had learned quickly that Spanish Florida offered a haven for runaways.”[33] In the eighteenth century, as European and American rice planters of the South Carolina and Georgia regions became more and more wealthy, the quality of life and treatment worsened for the forced laborers, and this caused the runaway slave population to increase in Florida. “Initially South Carolina’s agricultural economy was based on provisions gardening, naval stores, and cattle raising rather than monocrop plantations.”[34] As the planter’s desire for the monocrop plantation system grew, so did the Africans’ desire to flee. Once slaves learned that “runaways coming into Florida from South Carolina could obtain freedom if they embraced the Catholic faith,”[35] and flee they did. ‘Runaways from South Carolina began arriving in Saint Augustine as early as 1687.’[36] The Gullah runaways were running to the Spaniards in St. Augustine in La Florida, Spanish territory in North America during the colonial period. Spain colonized Florida in two different periods of the colonial era before they eventually relinquished the territory to the American colonists in 1821. They controlled the region from 1513 until 1763 when they bartered the territory for Cuba. This era became known as The First Spanish Period. Spain regained control in 1784 until 1821 (when they finally turned the area over to the United States) and this era became known as The Second Spanish Period. Although heavily involved in the African slave trade, the Spanish Crown, during their two periods of control, was not interested in large scale slavery in colonial Florida. Spain’s La Florida, more specifically, “St. Augustine was supported because of its strategic value in maintaining the defenses and economic functions of the Caribbean and the Bahama Channel could be protected from foreign powers. As a northern outpost, St. Augustine was also a buffer between the Spanish empire and the English colonies established in the Southeastern United States during the first decades of the seventeenth century,”[37] So, it was for this reason that the colonial “Spanish settlers has called the runaway black maroons, a West Indian word meaning ‘free Negroes,’ and had allowed them to settle among the Seminole Indians without paying much attention to them.”[38] This is where the Seminoles and Gullah-Geechee people would develop and cultivate their personal relationships as well as their agricultural and military alliances. “It seems likely that Spaniards first introduced blacks to the Seminoles.”[39] The Spaniards had settled St. Augustine in aboriginal territory, so native villages surrounded this fort from every angle. In their escape to the Spaniards, Africans encountered numerous bands of natives. “At the very time the Seminole bands were establishing a separate political identity in Florida,…their friends were treating Africans favorably. The Spaniards welcomed runaways from Southern plantations, gave them their freedom, and asked for little in return save for in their cooperation in repelling elements hostile to both parties. The way the Europeans treated their African associates well may have made an impression upon the Seminoles. The Spaniards allowed Africans to live apart, own arms and property, travel at will, choose their own leaders, organize into military companies under black officers, and generally control their own destinies. It seems probable that the early Seminoles would have been aware of these developments and that their initial perceptions helped determine the course of their own relations with blacks.”[40] The Africans tended to reside in very close proximity to the Seminole villages. Their settling close to their allies was strategic in that it allowed them to gather rather quickly during warfare. “As many as fifty communities of runaway slaves had existed in various times and places in North America from 1672 until 1864, but only those in Florida had lasted any length of time. The communities in Florida had managed to survive because of three factors: first, the Spanish had allowed the Indians driven from their homes in the southern states and the fugitive Negroes to settle on the border and had encouraged them to harass the settlers who were rapidly taking up the Indians’ lands; second, the English, operating from Florida, had actively recruited slaves and displaced Indians as allies in the Revolution and the War of 1812; and third, aborigines in the south, seeing the prestige which accrued to slave owners, had bought and stolen slaves or captured them in war.” There were many Seminole-African villages between 1690 and 1850. These settlements included forts, Seminole villages that housed Africans and independent Black Seminole villages. The two major fort settlements where the Black Seminoles lived were The Negro Fort (former British fort) and Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose also known as Fort Mose (former Spanish fort). There were Seminole villages in which Black Seminoles resided, possibly with their Seminole slave holder. These villages were: Cuscowilla (Bowleg’s Town I), Bowleg’s Town II off near the Suwanee River, Okahumpka, Powell’s Town, Chocahatti, and Sarasota. Sarasota is one of the villages that harbored runaway slaves and where survivors of the Negro Fort escaped to when it was leveled and destroyed by Colonel Duncan Clinch. Some of the autonomous African villages included: Mulatta Girl’s Town, Payne’s Town, King Heijah’s Town, Big Swamp, Pilaklikaha (or Peliklakaha), Buckra Woman’s Town, and Boggy Island. These town were created and developed by Black Seminoles (Landers, 1999). The Seminoles that had extensive contact with the Africans tended to follow the pattern of the Spaniards in their intimate dealings with them. The exact date of the beginning of the Seminole-African relationship is unknown. However, various sources place the beginning of their agricultural and military collaboration sometime around the last two decades of the eighteenth century. It was around this time “after Spanish authority had been restored in Florida in 1783, that the Seminoles first adopted black slavery.”[41] It appears that contact between the two grew as the desire for free labor increased. As human beings, we tend to be more alike than we are diverse. “Negroes and Indians, despite natural differences and white efforts to generate further antagonisms, had in common comparable personal and ancestral experiences in the subtropical coastlands of the southern Atlantic.”[42] Each lived very similarly as the other, in that, they used the land and its resources around them efficiently and effectively. Both incorporated communal agriculture and hunting as their economic arrangement “Moreover, not only were West Africans and Indians more accustomed to the flora and fauna of a subtropical climate generally, but both possessed an orientation toward the kinds of extreme familiarity with their biological environment, the passionate attention……to it and……precise knowledge of it which Europeans in Africa and America have in turn admired, belittled, and ignored.”[43] Each group also influenced the other a great deal. They tended to live in cabins built of palmetto and thatched leaves, dressed the same wearing turbans with plumes, bright hunting shirts, moccasins and polished metal necklaces and gaining nourishment feasting on the same victuals together.[44] Both the Spanish and Seminoles engaged in the institution of slavery in colonial Florida, but they did so with different intentions in mind. It seems very likely that both the Spanish and Seminoles knew how important the Africans as slaves were to the English and the Americans. My contention is that both parties used this knowledge to their advantage. “The Spanish approach to slavery tended to be more lenient than the British, employing less rigorous codes and affording blacks a greater degree of freedom.”[45] The Africans that fled to the Spaniards found acceptance and refuge at St. Augustine. Seminole natives had already lived near and had become allies with the Spanish by this time. This established relationship among the Seminoles and Spaniards made it easier for the Africans who “often escaped from slavery to form proximity to Seminole villages. The locations of the Seminole maroon communities were strategic in that it allowed them to gather quickly to engage in battle when necessary. The Seminoles seemed to have followed the Spaniard’s lead in their enslavement of the runaway blacks. They were said to have drastically altered the system of slavery. “In nearly all studies of slavery among the Indians, the Seminoles are cited as exceptions to the generalizations.”[46] This caused white Southern slaveholders to panic. Often, it is argued that slavery is slavery, however, the natives did not have capitalistic motives in mind when they enslaved another human being. We must keep in mind that “the Seminoles had enslaved other Indians before they encountered Africans, but they associated servitude with capture in warfare rather than an organized system of labor.”[47] The “captives were taken to restore depleted tribal populations and replace fallen kinsmen.”[48] Southern whites tended to fear that the natives and their African vassals would unite against them since ‘the Seminoles permitted Africans to own not only property but also guns for use in defense and for hunting. They could move around at will. There can be little doubt that the Seminole maroons were able to control most aspects of their existence.’[49] Also, according to Virginia Bergman Peters, in her book, The Florida Wars, “in the Florida Territory Negroes and Indians lived together in a rather relaxed relationship. The Negroes built their own villages, laid out and farmed their own fields (more efficiently and effectively than the Indians), and paid an annual tribute of corn, vegetables, beefs and hides to their Indian protectors. In return the Indian would insist that all blacks who paid the tax to him were his property and could not be claimed by slave catchers from the North.”[50] Lastly, “the Seminoles also considered managing slaves beneath the dignity of the warrior and alien to their culture. Thus, they attached new connotations to servitude, determined by their continuing need for a military alliance with the blacks.”[51] Therefore, it can be argued that the Seminoles’ idea of slavery meant something considerably different which may have contributed to their strong military and agricultural alliances with their vassals. Peters goes on to state that “in order to protect their allies, Indians had to insist to white authorities that the blacks were all slaves which they intended to defend from the depredations and claims of Americans.”[52] Initially, upon contact the Seminoles and Africans had established and “practiced a communal system of agriculture, their fields being set apart from those of the Seminoles.”[53] The Africans would share their crop with the Seminoles at harvest time. It would be during their disputes with the American military that the Seminoles would come to realize the significance of using their allies as interpreters/translators, guides, tactical advisors, tribunal counselors and spies.[54] “The first significant military alliance of Seminoles and blacks occurred during the so-called Patriot War of 1812” where a handful of native bands and Africans led by a free man named Prince Witen ambushed Captain John Williams and a group of Georgians seeking seizure of Florida. From this period up until the final battle of the Third Seminole War, the descendants of the Creek and those of the West African people continued to collaborate in the Battle of Burnt Corn, the Fort Mims Massacre, the Battle of the Holy Ground, the Negro Fort Massacre, the Battle of Fowltown, and the Battle of Suwannee during what became known as the First Seminole War. The Africans fighting alongside the Seminoles were not as prominent during this period, but no less significant. It was during the Second Seminole War battles of the Destruction of St. John’s Sugar Plantations (St. John Slave Revolt), Dade’s Massacre, the First Battle of Withlacoochee, the Seige of Camp Izard, the Second Battle of Withlacoochee, the Battle of Wahoo Swamp, the Battle at Hatcheelustee Creek, the Battle of Okeechobee, the Battle at Jupiter Inlet and the Battle of Lockahatchee that the relationships among the Seminole chiefs and their chief commanders of African ancestry became more significant and their military alliance more prominent. Their strong alliances became much clearer in 1835 when Seminole Chief King Philip and Black Seminole leader, John Caesar led natives and African freedom fighters on a raid destroying many of the white planters’ sugar plantations in the St. John’s River region of Florida. Also, in 1835, it was during Dade’s Massacre, that Chief Micanopy, Jumper and Alligator led a band of natives and Africans in a fort attack that killed Major Francis L. Dade, his military companion, his sutler and two clerks. During this attack, Micanopy and his men captured Dade’s guide and interpreter, Luis Pacheco, a slave hired out by his slave holder, Mrs. Antonio Pacheco. Luis Pacheco later served in the same capacity for the Seminoles after Dade’s untimely demise. At the Battle of Withlacoochee, also in 1835, it is said that between thirty and fifty Africans fought with Seminole leaders Osceola and Alligator. Two of the Seminoles’ fallen comrades had been Africans that were apart of Chief Micanopy’s house. During the Seige of Camp Izard in 1836, Abraham, a black Alachua chief, and John Caesar, a Black Seminole leader, both served as interpreters during Seminole negotiations with General Edmund P. Gaines. It must be noted here that Abraham was Micanopy’s chief commander and was said to have had a great influence over him. Micanopy was known to have made no decision without first seeking the counsel of Abraham. Several Africans and natives fought together with Osceola in the Second Battle of Withlacoochee, in 1836, where they were able to get General Winfield Scott and Major Benjamin K. Pierce’s troops to retreat from the Withlacoochee River. Also in 1836, General Thomas Sidney Jesup boldly stated how a runaway slave of a Florida planter was one of the most distinguished leaders fighting alongside the two principal commanders- Yaholoochee and Osuchee at the Battle of Wahoo Swamp. The Seminoles and their African allies had become so fierce an opponent for the United States Army that they brought in the United States Marine Corp. Colonel Archibald Henderson who led an attack against Osceola and his band of natives and Africans. The 1837 Battle of Hatcheelustee, believed to be led by the Alachua chief Abraham, also involved Ben and Primus, two slave messengers and interpreters utilized by Colonel Henderson and General Jesup’s camps to get word to the Seminoles about plans for negotiations to end the war. Again in 1837, there was yet another confrontation. The Battle of Okeechobee in which historians begin to document the collaboration of Mikasuki Seminole, Arpeika (Sam Jones) with Coacoochee (Wild Cat) and Alligator along with Black Seminole sub-chief John Horse and interpreters, John Philip, a slave of King Philip and Pompey. This particular collaboration of Seminoles and Black Seminoles led to a great many Seminole non-combatant captures. However, they gave Colonel Zachary Taylor great difficulty in the process. The Jupiter Inlet in 1838, was a minor incident as compared to previous conflicts that led to the Battle of Lockahatchee. This battle against Colonel Taylor and General Jesup led by Seminole, Tuskegee was the last major battle of the Second Seminole War. Tuskegee and about one hundred to one hundred and fifty Black Seminoles gave it one last fight. They were unsuccessful. Many of the major players for the Seminoles by this time had died, were taken ill or were captured awaiting deportation to Oklahoma via New Orleans.[55] Just when it appeared to have been all over, Holata Micco (Billy Bowlegs) and Ocsen Tustenuggee would rise up with new bands of natives and Black Seminoles only to begin the Third Seminole War. These two major players of this war, before being captured and deported, gave Lieutenant George Hartsuff, General William S. Harvey and Colonel Gustus Loomis a serious fight for the territory they considered home. Ben Bruner, an interpreter for Holata Micco became an important ally during this time. Jim Bowlegs, a slave of Haloto Micco and Sampson, both interpreters also appear at this time. All of the men serving as interpreters and guides were essential and influential during the United States-Seminole negotiations. The Third Seminole War battles between the American military, Seminoles and Black Seminoles only lasted for three years so some scholars of Native American History do not give much weight to its importance. However, the fact that these chiefs along with their vassal allies were able to strongly challenge the military campaigns of Clinch, Gaines, Jackson, Taylor and a few other Americans who were assigned to high level positions speaks volumes and is a testament to their character, military intelligence and bravery. They fought for as long as they possibly could; long, hard and to the bitter end. In each of the three wars, the Seminoles’ ability to promptly rally the Black Seminoles from very nearby villages into battle and their use of guerilla warfare tactics of lying in wait ambuscades, unloading a series of rapid shots and then retreating into the swamps or their hammocks proved very effective in undermining the best American military strategists and caused many casualties for US troops. According to Allman, “the Seminoles had what, in today’s counter-insurgency parlance, is called an integrated command structure.”[56] The capacity in which the Black Seminoles would play served to be fundamental not only in the fighting with the Seminoles against the Americans, but also in serving as their most important allies and interpreters during the negotiation procedures. During slavery, the Seminoles’ presence in Florida would constantly serve as a problem for American slave holders, planters, colonists, military personal and political administrations. For as long the original inhabitants resided on their land and provided safe harbor, Seminole maroons and runaway slaves would be attracted to Florida seeking refuge from the American form of bondage. The Seminole presence threatened the white American’s way of life and their form of slavery was not profitable for them. This is evidenced in their continuous effort during military negotiations, conferences, and treaty procedures where they pressured the Seminoles to return runaways, their determination in trying to keep the two groups apart as well as their alliances with the Lower Creeks and their payments to them to act as slave catchers. Consistently, “the slave question was at the root of the war”[57] and slave holders were in constant fear of the Native American-African alliance, so they forcibly removed the Seminoles from their lands in an effort keep the Africans enslaved, and without consequence. “In the period from 1783 to 1858, the fugitive slaves among the Seminoles in Florida – or the fear among American slave owners of such fugitives- were among the main reasons for, first the American capture of Florida, and second, the wars against the Seminoles and their eventual deportation to Indian Territory in Oklahoma.”[58] The Seminole and African collaboration was an alliance formed for the survival of both parties. Each used the other to accomplish two goals: maintaining a homeland and securing freedom. A uniquely created group- The Black Seminoles evolved from this alliance. No other group in American history has caused more controversy concerning ethnicity than the Black Seminoles. “The term seems self-contradictory simply because race runs too deep in the American psyche to be understood as a social construct.”[59] Micco explains that the “Africans and Seminoles constituted hybridized entities who occupied liminal spaces in metaphorical and physical senses. Specific African tribal origins had been erased from the Middle Passages on, and Seminole identity was a byproduct of an amalgamation of aboriginal tribal remnants. Together, Africans and Seminole identity made up a New People, a multiracial alliance that threatened the neat black-white racial categories of the slave-holding South.”[60] The Black Seminoles of the late eighteenth, early nineteenth centuries seems to be a phenomenon to society. Mulroy cites, Nancie Gonzalez, whose sheds more insight on why. The Black Seminoles fall into what she calls a neoteric group. She defines a neoteric group as ‘a type of society which, springing from the ashes of warfare, forced migration or after calamity, survived by patching together bits and pieces from its cultural heritage while at the same time borrowing and inventing freely and rapidly in order to cope with new completely different circumstances.’[61] This would accurately explain the Black Seminole situation. “When the Seminoles were removed from Florida between 1838 and 1843, nearly five hundred persons of African descent accompanied them to the West.”[62] Their struggle continued in Oklahoma because food rations provided were limited, land was not expeditiously allocated, and money promised by the United States government was not paid in a timely manner. Those that were free consistently attempted to evade slave catchers, some remained in bondage and struggled to gain their freedom, while others lived miserably in poverty. This caused a large number of Black Seminoles to migrate to Nacimiento, Mexico. When they wished to return to Oklahoma from Mexico for various reasons, there was more discrepancy surrounding whether they should be allowed to return to American soil. Finally, the latest controversy being who should be permitted to receive money from the government issued funds to the various Nations. The Natives argue that the Black Seminoles are not of Native ancestry, therefore, should not benefit from the monies paid to their Nations. Court cases have been heard to address this issue. Although, forcibly relocated to a region of the United States not originally suitable to them, Native Americans have received some type of compensation. Unfortunately, the fight for the Black Seminoles has continued well into the twenty-first century. [1] Katz, William Loren, 1986, Black Indians: A Hidden Heritage, New York, Atheneum Books for Young Readers, p. 5 [2] Allman, T.D., op. cit., p. 90 [3] Milanuch, Jerald T., “A Creek Sourcebook; A Seminole Sourcebook” Review by William C. Sturtevant in the Florida Historical Quarterly, 1989, Vol 67, No 3, p. 366 [4] Micco, op. cit., p. 125 [5] Littlefied,Jr., Daniel F., 1979, African and Creeks: From the Colonial Period to the Civil War, Westport, Greenwood Press, p. 255 [6] Mulroy, Kevin, 1993, Freedom on the Border: The Seminole Maroons in Florida, the Indian Territory, Coahuila, and Texas, Lubbock, Texas Tech University Press, p. 7 [7] Wright, Jr., J. Leitch, 1986, Creeks and Seminoles: The Destruction and Regeneration of the Muscogulge People, Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press, p. 3 [8] Covington, James W., “Migration of the Seminoles into Florida, 1700-1820,” The Florida Quarterly, 1968, Vol 46, 4, p. 340 [9] Mahon, John K., 1991, History of the Second Seminole War, 1835-1842, Gainesville, University of Florida Press, p. 4 and Porter, Kenneth W., 1996, The Black Seminoles: History of a Freedom Seeking People, Gainesville, University Press of Florida, p.27 [10] Sturtevant, William C., “Creek Into Seminole,” in Burke-Leacock, Eleanor and Oestreich-Lurie, Nancy, ed., 1971, North American Indians in Historical Perspective, New York, Random House, p. 103 [11] Mahon, op. cit., p. 7 [12] Sturtevant, “Creek Into Seminole,” op. cit., p. 103 [13] Ibid, p. 107 [14] Saunt, Claudio, “The English Has Now a Mind to Make Slaves of Them All”: Creeks, Seminoles, and the Problem of Slavery, American Indian Quarterly, 1990, Vol 22, No 1/2, p. 158 [15] Wright, “Creek into Seminole,” op. cit., p. 2 [16] Ibid, p. 5 [17] Littlefield, Africans and Seminoles, op. cit., p. 4 [18] Twyman, Bruce Edward, 1999, The Black Seminole Legacy and North American Politics, 1693-1845, Washington, D.C., Howard University Press, p. 11-12 [19] Ibid, p. 12 [20] Ibid, p. 15 [21] Ibid., p. 11-12 [22] Forbes, Jack D., 1993, Africans and Native Americans: The Language of Race and the Evolution of Red-Black Peoples, Urbana, University of Illinois Press, p. 63 [23] Ibid, p. 192 [24] Gidding, Joshua R., The Exiles of Florida, op. cit., p. 3 [25] The following discussion on the origin of the term Seminole has been taken primarily from Creeks and Seminoles, Wright (Lincoln, University of Nebraska, 1986) The Seminole Freedmen, Mulroy (Norman, University of Oklahoma Press, 2007 and Africans and Seminoles, Littlefield (Jackson, University Press of Mississippi, 1977) [26] Twyman, op. cit., p. 15 [27] Deagan, Kathleen, “Sixteenth-Century Spanish American Colonization in the Southeastern United States and the Caribbean,” in Thomas, David Hurst, ed., 1990, Columbian Consequences: Archaeological and Historical Perspectives on the Spanish Borderlands East, Washington, Smithsonian Institution Press, p. 231 [28] Landers, Jane, “African Presence in Early Spanish Colonization of the Caribbean and the Southeastern Borderlands,” in Thomas, David Hurst, ed., 1990, Columbian Consequences: Archaeological and Historical Perspectives on the Spanish Borderlands East, Washington, Smithsonian Institution Press, p. 321 [29] Opala, Joseph, A., “The Gullah: Rice, Slavery and Sierra Leone-American Connection,” http://www.yale.edu/glc/gullah/07.htm [30] Ibid [31] Amos, Alcione M., “Black Seminoles-The Gullah Connection,” The Negro Scholar, 2011, Vol 41, 1, p. 32 [32] Ibid [33] Mulroy, Freedon on the Border, op. cit., p. 8 [34] Riordan, Patrick, “Finding Freedom in Florida: Native Peoples, African Americans and Colonists, 1670-1816,” The Florida Historical Quarterly, 1999, Vol 75, No 1, p. 25 [35] TePaske, John J., “The Fugitive Slave: Intercolonial Rivalry and Spanish Slave Policy, 1687-1764,” in Proctor, Samuel, 1975, Eighteenth-Century Florida and It’s Borderlands, Gainesville, University Presses of Florida, p. 3-4 [36] Mulroy, Kevin, 2007, The Seminole Freedmen: A History, Norman, University of Oklahoma Press, p. 7 [37] Deagan, Kathleen A., “Accommodations and Resistance: The Process and Impact of Spanish Colonization in the Southeast” in Thomas, David Hurst, ed., 1990, Columbian Consequences: Archaeological and Historical Perspectives on the Spanish Borderlands East, Washington, Smithsonian Institution Press, p. 302 [38] Peters, Virginia Bergman, 1979, The Florida Wars, Hamden, Archon Books, p. 19 [39] Mulroy, Freedom on the Border, op. cit., p. 8 [40] Ibid, p. 10 [41] Ibid, p. 11 [42] Wood, op. cit., p. 116 [43] Wood, op. cit., p. 117 [44] Mulroy, Freedon on the Border. op. cit., p. 20 [45] Ibid, p. 8 [46] Littlefield, Africans and Seminoles, op. cit., p. 6 [47] Mulroy, Freedom on the Border, op. cit., p. 8 [48] Bolt, Christine, 1987, American Indian Policy and American Reform: Case Studies of the Campaign to Assimilate the American Indians, London, Allen & Unwin, p. 149 [49] Mulroy, Freedom on the Border, op. cit., p. 19 [50] Peters, op. cit., p. 18-19 [51] Mulroy, Freedom on the Border, op. cit., p. 17 [52] Peters, op. cit., p. 98 [53] Mulroy, Freedom on the Border, op. cit., p. 19 [54] The dialogue regarding the usefulness of the Africans has been taken from Sturvetant, “Creek into Semimole,” Mulroy, Freedom on the Border, and Porter, Black Seminoles, passim [55] The Seminole Wars summarization dialogue taken from Porter, The Black Seminoles, Mulroy, The Seminole Freedmen, Mahon, History of the Second Seminole War, and Hatch, Thom, 2012, Osceola and the Great Seminole War: A Struggle for Justice and Freedom, New York, St. Martin’s Press, passim [56] Allman, op. cit., p. 142 [57] Littlefield, Africans and Seminoles, op. cit., p. 19 [58] Sturtevant, William C., “Commentary,” in Proctor, Samuel, ed., 1975, Eighteenth-Century Florida and Its Borderlands, Gainesville, University Press of Florida, p. 40 [59] Allman, op. cit., p. 145 [60] Micco, in Miles, Crossing Waters, Crossing World, op. cit., p. 125 [61] Mulroy, Freedom on the Border, op. cit., p. 23 [62] Littlefield, Africans and Seminoles, op. cit., p 4Who Are the Seminoles?

Seminole Migrations into Florida Territory

The Emergence of the Seminoles: Two Views, Mono and Polygenesis

How the Upper Creeks Became Seminoles

Who Are the Gullah-Geechee?

The Gullah-Geechee Escape South Instead of North

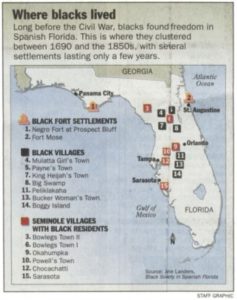

Seminole-African Villages in Florida

African Slavery in the Seminole Nation

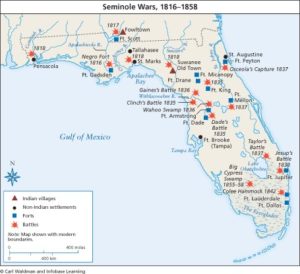

The Seminole-African Collaboration in the Seminole Wars

The Seminole Legacy and Issues Today

The objective of “The Seminole and African Collaboration: An Alliance for Survival” is to introduce our middle grades, specifically seventh and eighth grade students to a segment of Native American history that is intertwined with the histories of Africans and African-Americans Common Core Standards in compliance with the Pennsylvania Common Core Standards for Reading and History. The goal is to implement student lessons that will increase our students’ information base, content comprehension, knowledge retention level and critical thinking skills. The unit is interdisciplinary in that it can serve to supplement the American History, African American History and English curricula. Within the American History curriculum, it can be used to discuss events leading up to the Seminole War and how the American government, via presidential administrations, dispossessed thousands of indigenes of territory they considered their hunting and gathering grounds (CC.8.5.6-8.A., CC.8.5.6-8.B., CC.8.5.6-8.C., CC.8.5.6-8.D., CC.8.5.6-8.CH. and CC.8.5.6-8.J.). Primary source analysis can be utilized effectively here (CC.8.5.6-8.G. and CC.8.5.6-8.I.) This unit can fit within the confines of the African American History curriculum in multiple ways as a consequence of so many missing links of African American history from our textbooks and school curriculums. It can be utilized to tell the story of how the Black Seminole Nation was created, the history of the African and Native American economic, social, political and cultural connections as well as the strong alliances formed that challenged colonial powers. It can address the two groups serving together in European bondage together, name labeling, the Seminole leaders and their chief commanders of African ancestry, Seminole slavery versus Spanish slavery versus English slavery, in addition to primary source document analysis of images of the Seminoles and Africans. (The same above-referenced Common Core Standards utilized for American History in addition to standards CC.8.5.6-8.E and CC.8.5.6-8.F). In the English curriculum, students can engage in various reading passages from the unit to address literary skills such as analyzing text to determine central ideas and text development (CC.1.2.7.A), citing textual evidence (CC.1.2.7.B), supporting details, summarization (CC.1.2.7.A.), how text makes connections and distinctions among events and individuals (CC.1.2.7.C.), vocabulary development that focuses on the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in text (CC.1.2.7.F., CC.1.3.7.F. and CC.1.3.7.G), author’s point of view (CC.1.2.7.D.), comparing and contrasting (CC.1.2.7.G., CC.1.3.7.G. and CC.1.3.7.H.), determining fact from opinion (CC.1.2.7.I.), making inferences and drawing conclusions (CC.1.2.7.B. and CC.1.3.7.B.) and finally, evaluating arguments and specific claims (CC.1.2.7.H.). Dialogue and discussion (CC.1.5.7.A., CC.1.5.7.B., CC.1.5.7.D. and CC.1.5.7.G) using the Socratic Circle method can be useful in all three curriculums to assess whether the reasoning is sound and if the evidence cited is relevant and sufficient. Socratic Circle is important for developing the student’s skills of recognizing when irrelevant evidence is introduced, analyzing when two or more pieces of text provide conflicting information regarding the same topic and identifying where the texts disagree on matters of fact or interpretation. See Content Standards for full description of Common Core Standards.

“The Seminole and African Collaboration: An Alliance for Survival” will incorporate the Common Core Standards for both History and English. The new common core offers greater teacher flexibility in the classroom allowing for more lesson creativity. A diverse level of pedagogical techniques and educational stratagem will be utilized to achieve the above-referenced aims. In addition to text, video technology, the use of films, music and high interest actively engaging activities will be integrated into student lessons. The Seven Step Lesson Plan is used by the School District of Philadelphia and will be implemented in this unit. This teaching strategy involves an Objective, Do Now, Direction Instruction, Guided Practice, Independent Practice, Closure, and Exit Ticket. Homework is assigned daily as an extension of the current skill taught. These seven steps plus the homework is posted daily and referred to repeatedly during the class period to drill students for skill knowledge and comprehension. The posted Objective should begin with IWBAT (I will be able to) followed by the skill and in teacher lesson plans read, SWBAT (student will be able to). The Objective states what knowledge or skill the lesson would like the students to achieve. The Do Now is a brief exercise that precedes the lesson. It should relate to the lesson or be a review of the previous lesson taught. Direction Instruction is the teacher-centered activity of the lesson. It is during this time that lesson content material is introduced. Guided Practice allows the lesson to be modeled for the students. Although, lesson modeling occurs here, the lesson should be modeled for students as many times as needed. Independent Practice allows students to work independently as evidence that they actually understand the lesson that has been taught. There should be no teacher involvement during the independent practice component. This is the opportunity for teacher notes to be taken to determine student comprehension, if the lesson needs to be re-taught and if new pedagogical strategies and techniques need to be incorporated to re-introduce the lesson. Students should be able to answer a relevant question to from the lesson. Closure allows teachers to conduct a mini pre-assessment with brief wrap-up questions. This portion also allows teachers to determine if the lesson should be re-introduced to students. The final piece of the steps is the Exit Ticket. Students should be able to summarize or cite verbatim the objective and provide a brief synopsis of the knowledge they have acquired during the class. This is typically a written piece completed before five –ten minutes before the closure of the lesson. Homework is given daily as an extension of the lesson to improve mastery of the skill or topic taught. Graphic organizers will be used to help organize information from the lesson, primary and secondary source images and documents will be used as visual tools to help make real life connections as well as dialogue and discussion to improve speaking and listening skills. Modifications and accommodations will be made during the implementation of the lessons and activities to address the many student learning styles as well as to differentiate instruction.

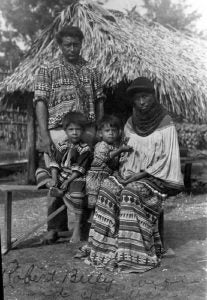

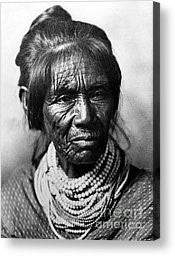

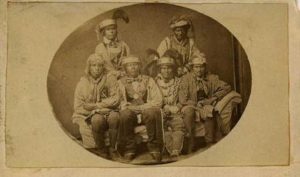

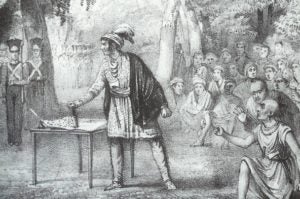

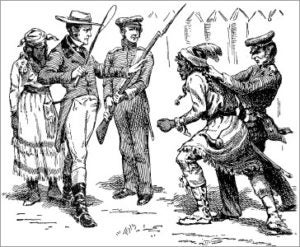

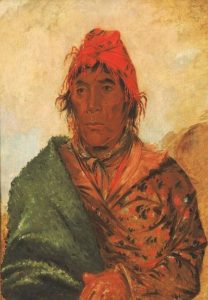

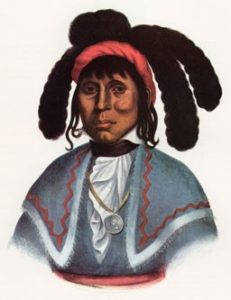

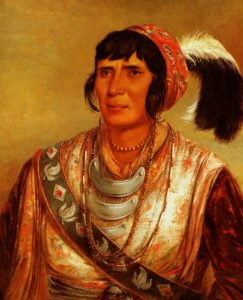

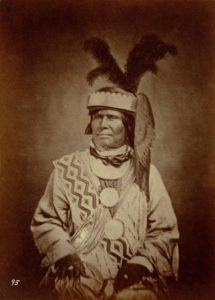

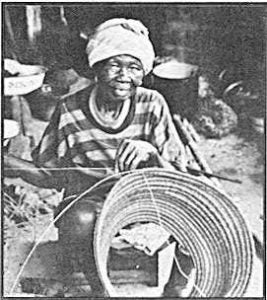

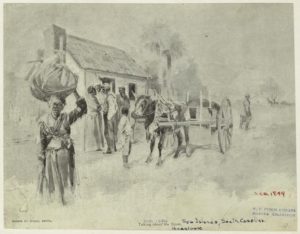

The following lessons are brief introductory lessons to introduce a skill set. They should be modified and extended during implementation. SWBAT explain what an indigenous person is and describe at least one group from each region of the United States using a web and Venn diagram graphic organizers to organize as well as to compare and contrast content information. Vocabulary: indigenous, aboriginal, aborigines, inhabitant, comprise tri-sate Driving Question: Who are the original inhabitants of the Americas? What does the term indigenous mean? Do we still have indigenous people in America today? What groups of people comprise the various indigenous groups of our tri-state region (Pennsylvania, Delaware and New Jersey)? Who are the southeastern Native Americans of the United States? What terms might be considered offensive to the original inhabitants of this country? Should indigenous people be called Indians, natives, Native Americans, or by their aboriginal name? What else would I like to know? SWBAT describe who the Seminoles are using a web graphic organizer and primary source images. Vocabulary: Seminole, originate, primary source, migrate Driving Questions: How did the Seminoles originate as a group? How did they end up in colonial Florida? Do the Seminoles exist today? What regions did they originally migrate from? What language or languages did they speak? Is this language spoken today? Who were their leaders? Why did the United States government remove them to Oklahoma? Where are the Seminoles today? What else would I like to know? Primary Source Document Analysis: Describe the images of the Seminoles. For each primary source answer the following questions: What do you see in the image? Where are the people in the image? What are they wearing? Who is in the image? When do you think the image was taken? Describe the background. Does the photo look current or is it from the past? What else would I like to know? State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory SWBAT to identify and explain the Seminole chiefs who were instrumental in the battles of the Seminole Wars using primary source images, a three column note and triple ring Venn diagram graphic organizers. SWBAT to explain the significance of each war, the role each chief played, military strategy and why they were successful using a three column note graphic organizer and group discussion. Vocabulary: Emathla, Micconuppe, Asi-Yahola, Coacoochee, Yaholoochee, Holata Micco Driving Questions: Who are the great Seminole leaders of the First, Second and Third Seminole Wars? Why were they fighting? How essential was their role as a leader in a particular war? Who were the military authorities they challenged? What else would I like to know? Primary Source Document Analysis: Describe the images of the Seminoles Chiefs. For each primary source answer the following questions: What do you see in the image? Where are the people in the image? What are they wearing? Who is in the image? When do you think the image was taken? Describe the background. Describe their facial expressions. Does the photo look current or is it from the past? What else would I like to know? Ee-mathla (King Philip) Micconuppe (Micanopy) Asi-Yahola (Oseola) Coacoochee (Wild Cat) Yaholoochee (Cloud) Holata Micco (Billy Bowlegs) SWBAT describe who the Gullah-Geechee people are and their background using a web graphic organizer. SWBAT describe the commonalities shared by as well as the differences among the Seminoles and the Gullah-Geechee using a two column note and Venn diagram graphic organizer. SWBAT explain the circumstances that allowed the Gullah-Geechee to use their own agency in securing their freedom using Socratic Circle. Vocabulary: Gullah, Geechee, Lowcountry, weaver, commonalities Driving Questions: Who are the Gullah-Geechee people? Where are they from? What did the Seminole Native Americans and the Gullah-Gechee people have in common? Primary Source Document Analysis: Describe the images of the Gullah people. For each primary source answer the following questions: What do you see in the image? Where are the people in the image? What are they wearing? Who is in the image? When do you think the image was taken? Describe the background. Describe their facial expressions and body language. Does the photo look current or is it from the past? What else would I like to know? South Carolina Gullah, about 1900. Charleston street Vendor Gullah Ring Shouters Gullah Basket Weaver Library of Congress SWBAT explain what an alliance is and the importance of having allies using a cooperative group activity, Socratic Circle and video technology. Vocabulary: Socrates, Socratic Circle, alliance, allies, collaboration, cooperative, efficient, effective, debrief Driving Questions: What is an alliance? Why is it important to form alliances? What else would I like to know? Cooperative Group Activity: Part I: Divide the class evenly into groups of four (4). Distribute a twenty (20) piece puzzle to each group (the amount can vary based on student academic level). Have alternating groups work collaboratively to complete the puzzle with each member responsible for a task (timer, puzzle piecer, organizer, helper, etc.). Have the other groups choose one person in their group to work on the puzzle independently. Assign a “Camera Crew” to video their peers at work using a camcorder, iPad, or laptop. Observe which of the groups completes the task efficiently and effectively. Review the taping using a Smart Board or white wall and a laptop or iPad. Have students debrief the results of what was effective and what was not. NOTE: Puzzles can be purchased from a dollar store. Part II: Using the classroom chairs form a large circle. Have students sit in the circle. Review the guidelines for Socratic Circle prior to the group discussion. Reiterate the guidelines each time dialogue and discussion is conducted to ensure that everyone is familiar with how it is implemented. Extend this lesson based on the previous classroom exercise to discuss: What is an alliance? Why are alliances formed? Why do we align ourselves with certain people or groups? How are alliances formed and negotiated? Why are alliances dissolved? How are alliances maintained? Discuss the circumstances that caused the Seminoles and Africans to collaborate. To make a real life connection, include: Why is it important for people to work together? Have a student jot down student responses on chart paper. Also, have the “Camera Crew” video this exercise and review it later for a student debriefing session. SWBAT to explain what rebellion is and why it occurs using background knowledge and information about the Seminoles and Africans during the Seminole Wars as well as a cooperative group activity. SWBAT explain the various categories of rebellion, how they affect resistance and how the community is disrupted using a written piece that incorporates lesson notes from The Black Seminole Legacy and North American Politics, 1693-1856 by Bruce Edward Twyman and video technology. Vocabulary: rebellion, rebel, resistance, incorporate, disrupt Driving Questions: What is rebellion? Why do people rebel? What level of rebellion did the Seminoles and Africans exhibit during the Seminole Wars? What else would I like to know? Part I: Introduce rebellion, what it is, why it happens and who is involved. Part II: Introduce Twyman’s research on the various categories of rebellion (Levels A, B, C, D and E) and the affect each level has on resistance. This information will be derived from teacher made notes (refer to The Black Seminole Legacy and North American Politics, 1693-1856 by Bruce Edward Twyman, pages 7-10 to develop). Cooperative Group Activity: Part III: Divide the class into groups of 4. Assign a problem and a Level of rebellion (teacher made assignment-TMA) to each group and have the students perform an impromptu skit. Have the assigned “Camera Crew” video the skit performances. Review the tapings for student debriefing and assessment. SWBAT explain the significance of the Black Seminoles’ role for both the Seminoles and white settlers as interpreters, translators, and guides using primary source images, chart graphic organizer, a cooperative group activity and video technology. Vocabulary: interpreter, translator, comrade, prominent, personnel, settler Driving Questions: What were the roles of the Black Seminoles as allies of the Seminole comrades? What was the title and role of Abraham, John Horse, Luis Fatio Pacheco and Ben Bruner? Under which Seminole leader did each command? Which military personnel did each battle? In what time frame was each man prominent? What else would I like to know? Abraham John Horse Ben Bruner Cooperative Group Activity: Divide students into small cooperative groups. Have them discuss how to create a chart showing the military alliances of the Seminoles and Africans. The Second Seminole War exhibited the strongest collaboration of the two. Below is an example of what student work may look like. Student results will vary. Have the “Camera Crew” video the activity. Have students review and debrief the activity. Seminole-African Alliances: Battles of the Second Seminole War (King Philip, Mikasuki-Seminole Chief) (interpreter) (Alachua Chief and interpreter) Luis Pacheco (slave guide and interpreter) Alligator 30-50 black soldiers Alligator Holata Micco John Caesar (interpreter) Captain Ethan Allen Hitchcock General Duncan L. Clinch (slave interpreters) Osuchee Ben (messenger) Primus (messenger) General Thomas Sidney Jesup John Philip (translator) Pompey (interpreter) General Thomas Sidney Jesup SWBAT identify and determine the proximity of the various Seminole villages and maroon communities located throughout Florida using a map of Florida, a list of the villages, a cooperative group activity, video technology and Socratic Circle discussion. Driving Question: Why did the Seminoles and maroons keep their villages near one another? What were the benefits of the Seminole and maroons living in close proximity to one another. How does living in close proximity to an ally reinforce the collaboration of the two? What else would I like to know? Part I: Using a map, have students measure the distance of the Seminole villages from the maroon villages. Based on the calculated distances, have them determine how far in real distance and time the Seminole villages and maroon settlements would have been from one another. Cooperative Group Activity: Part II: In collaboration with colleagues, divide students into four large groups to assimilate Seminole settlements and maroon villages. Station the mock villages in various locations in the school, leave a village in the original classroom. Without using any modern forms of technology (other than the video team), have students work cooperatively to create ways of contacting and physically reaching one another to assemble for an alliance. Have a student “Camera Crew” video the activity. Observe which group is more efficient and effective. Allow students to regroup, review and debrief their results. Map of Florida (part of GA and AL) Courtesy of The Palm Beach Post, 2001 Staff Writer, Scott McCabe SWBAT explain the events of the Seminole Wars, describe the major players of Seminole descent and African ancestry that were involved in these wars, their significance in the wars, the circumstances that led to their military alliances, the affects that their alliances had on the United States government and its military using some form of technology for a class presentation (i.e, Prezi, blog site, video, etc.) or SWBAT address one of the following lesson components listed above using a PowerPoint presentation or a trifold board presentation along with a two-page typed essay.Lesson 1:

Lesson 2:

Lesson 3:

Lesson 4:

Lesson 5:

Lesson 6:

Lesson 7:

Battle (year)

Seminole Chief

Black Seminole

Military Commander

Destruction of St. John’s Sugar Plantation Raids (1835)

Emathla

John Caesar

General Edmund P. Gaines

Dade’s Massacre (1835)

Micconuppe (Micanopy)

Abraham

Major Francis L. Dade

Battle of Withlachochee (1835)

Asi-Yahola (Osceola)

Abraham

General Duncan L. Clinch

Seige of Camp Izard (1836)

Asi-Yahola (Osceola) Jumper

Abraham

General Edmund P. Gaines

Second Battle of Withlacoochee (1836)

Asi-Yahola (Osceola)

Cudjo and Billy

General Winfield Scott Major Bejamin K. Pierce

Wahoo Swamp (1836)

Yaholoochee

“runaway, property of a Florida planter”

Governor Richard Keith Call

Battle of Hatcheelustee (1837)

Asi-Yahola (Osceola)

Abraham

Colonel Archibald Henderson (Marine Corp)

Battle of Okeechobee (1837)

Coacoochee (Wild Cat)

John Horse (sub-Chief and interpreter)

Colonel Zachary Taylor

Jupiter Inlet (1838)

Seminole soldiers

African soldiers

Lieutenant Levi M. Powell

Battle of Locahatchee (1838)

Tuskegee

100-150 Black Seminoles

Colonel Zachary Taylor

Lesson 8:

Lesson 9: