Most American diets include industrially produced meat. Because this kind of meat production has significant impacts on greenhouse gas emissions, deforestation, and water pollution, reducing or eliminating its consumption is often targeted as one of the personal choices people can make to lessen their environmental impact. However, the choice itself does little to change the underlying industrial system. By inviting students to have strong emotional and visceral reactions to the reality of “how animals become meat,” this unit asks them to reflect on where their food comes from and how their values are violated or supported while watching and listening to industrialized slaughter. Groups of students then compare their personal value systems with the values espoused by the economic systems that created these industries, e.g. capitalism and communism, and discuss whose power and priorities are considered during decision making.

Turn off the lights! Conserve water! Recycle! These are just a few of the Fifty Simple Ways Kids Can Save the Earth (The EarthWorks Group, 1990). A little too simple for such a big outcome, no? Of course, these are satisfying and important ways of connecting with nature, but someone’s personal choices having planet-scale impact is largely determined by the political system around them and how much power they have within it. For the vast majority of American public school students, “environmental science” never mentions those larger systems, let alone subjects them to the critical inquiry that should be fostered by the sciences. For ninth graders at Furness High School, it has been much easier to focus on environmentalism as personal choice. We clean up litter together. We go outside and write about the garden. We generate electricity to show it’s a resource worth conserving. When these young people, who are largely from low-income families, are asked to use a carbon footprint calculator, most will be told that the best way to help the Earth is to eat less meat, that every kilogram of beef produces 100kg of “carbon dioxide equivalents” (Poore & Nemeck, 2018). While this may be true, it is unsettling. For one, British Petroleum coined the phrase “carbon footprint” as a way to shift responsibility from companies to consumers (Ackerman & Chakrabarti, 2023). It is an unfair and a disproportion responsibility to task public school students in Philadelphia with “saving the planet.” For two, even if someone makes that choice, it does almost nothing to change the underlying system or outcomes. They are no more equipped to evaluate how things got that way or to advocate for political change. Academic standards have left little room to focus on this kind of analysis. However, in July of 2025, Pennsylvania moves to a new set of science standards, including a requirement for students to: Demonstrate how systems thinking involves considering relationships between every part, as well as how the systems interact with the environment in which it is used. (PA STEELS 3.5.6-8.FF) “Environment” includes social structures like culture and the economy. By contrasting two different economics systems and their history of industrial meat production, I propose three activities to help students explore how society’s priorities shape our values, bodies, and environment. The first gets students talking about “value” and what they find valuable. In the second, they describe aspects of meat production intentionally kept out of sight and mind. Finally, students evaluate different priorities in decision-making for one of their own choice. The Rise of the Soviet Union In simple terms, an economic system is a way of distributing goods and resources in society. There are many different theories of how to accomplish “ideal” or “more optimized” distributions, and thinking about what to value has been a human occupation since almost the beginning of writing (Karahashi, 2020). A direct influence on those arguments has been the increase in material wealth brought about by the Industrial Revolution. From the 1760s through the 1840s, new social relationships emerged as increasing demand for labor by mills and factories concentrated populations and power in urban centers (Yuko, 2021). It also exacerbated income inequality (Blohkin, 2023). People who owned “the means of production” became richer, while people who sold their labor for wages were exploited at work and by the newly formed “other portions of the bourgeoisie, the landlord, the shopkeeper, the pawnbroker, etc.” (Marx, 1848). This is the world that birthed The Communist Manifesto. First published by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in February 1848, it analyzed how the beneficiaries of Modern Industry, the bourgeoisie, had reshaped both systems of value and the material world itself. With great poetic flair, they declared all “idyllic relations” between communities and families had been put to an end, replaced with “naked self-interest” and “callous cash payment.” All relationships could be reduced to power dynamics, a pattern of superiority and domination that applied to the Earth as well as fellow humans. This included, Subjection of Nature’s forces to man, machinery, application of chemistry to industry and agriculture, … clearing of whole continents for cultivation (Marx & Engels, 1848). Not only was the natural world cleared in pursuit of profit, it was replaced by vast urban centers that dramatically changed how people experienced “the land.” A Russian peasant relocating to Moscow in the 1890s described “inexplicable terror before the grandiose appearance and cold indifference” of his surroundings (Kanatchikov, 1986). His multi-unit apartment building was noisy and crowded. He missed “the meadows, the brooks, the bright country sun” that had been replaced by the turpentine of the factory and the acrid stench of courtyards. For the generations of people who have only known urban living, that sensuous knowledge of meadows or brooks has no replacement. The Industrial Revolution and its subsequent urbanization contributed hugely to how everyday people experience and value the environment. While acknowledging the miseries of this new world, Marx and Engels also identified a solution. They proposed social classes would be eliminated by an inevitable revolution of laborers, the proletariat, thus ending a division of power whose conflicts had been the source of history for “all hitherto existing society” (Marx & Engels, 1848). In this classless utopia, production would not be directed by individuals with capital. Rather, the means of production would be “concentrated in the hands of a vast association….” Once this cooperative arrangement had the springs of wealth flowing more freely, Marx describes a simple distribution strategy, “to each according to his need” (Marx, Engels, Lenin, 1970). This new system attempted to move the power of decision making from people with capital to the people who did the work. While incendiary in terms of theory and history, the Manifesto said little about how to actually administer that process. This was the situation Bolsheviks found themselves in after taking over Russia’s Provisional Government in October of 1917 (November 6th and 7th, under the Gregorian calendar). Guided by Marxist theory and hastened along by the “crisis and catastrophe” of an interim power structure following the tsar’s abdication, immediate negotiations of the revolution were conducted amidst gunfire and cigarette strewn floors (Mstislavskii, 1988). What resulted was a bloody civil war, millions of deaths in a country already devastated by WWI, and, in 1922, The Treaty on the Creation of the Soviet Union. Adopted in Moscow on December 30th (though never actually voted on by the Congress of Soviets), this text consolidated four republics into one nation, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, or USSR (Roudik, 2013). The largest country to ever exist, its sixty-nine-year lifespan proved an economic and social experiment with profound implications for the world. Landmarks in Soviet Meat Production “The food question” was immediately on the mind of these early revolutionaries. Nearing the end of the nineteenth century, more than half the land in tsarist Russia had been held in a form of collective ownership by peasants, called the “obshchina” (Marx & Engels, 1882). In a preface to the Russian translation of The Communist Manifesto, its authors wondered if this “primeval” system of ownership could transition directly to communism or if its feudal legacy would need to be dissolved before being brought into “the higher form of Communist ownership.” During the Civil War years under Lenin, violent grain seizures put the two systems into frequent opposition with terrible harvests and widespread scarcity as a result (Fainsod, 1970). Recognizing concessions needed to be made, the New Economic Policy was adopted from 1921 to 1928 (Fainsod, 1970). Although it still largely put agricultural policy in the hands of centralized bureaucrats instead of farmers, it was generally well received by peasants for allowing them to lease their land, hire labor, and sell surplus grain. These anti-Communist practices, however, were not well received by urban Party members and caused political friction for Lenin. It also did not solve the problem of producing enough grain for urban consumption and export. Because there were so few consumer goods to buy, peasants did not always have incentive to sell their grain. With the first Five-Year Plan committed to heavy industry and industrialization, the regime needed another way to supply grain at low prices (Fainsod, 1970). At the hands of general secretary Joseph Stalin, the human toll of this solution would be devastating. The new policy of collectivization started voluntarily in 1928 (Fainsod, 1970). State-owned farms, called sovkhozes, were introduced in arid, sparsely settled regions of the USSR. A lack of water and intense labor demands resulted in frequent crop failures, and huge investments in tractors and combines were met with ineffective operators and frequent breakdowns. Meanwhile, the collective farms, called kolkhozes, were slow in starting out. Only about 4% of peasants voluntarily collectivized between 1928 and October 1929, in response to which Stalin used force, threats, and discriminatory taxation to great statistical success, yielding 58% enrollment by March 1930. The reality, as reports soon showed, was that peasants were only enrolled on paper. Instead, they were refusing to work and slaughtering their livestock ahead of confiscation. The results were disastrous. Total number of livestock fell by half (Hubbard, 1939). Despite abysmal harvests in 1931 and 1932, grain was seized by compulsory “contracts,” and deaths directly attributed to starvation are estimated at four million peasants (Applebaum, 2017). It was in the midst of this “everyday experience of paucity” that the government began trumpeting the arrival of “plenitude and happiness” (Goscilo, 2009). While the early years of Bolshevik rule had celebrated self-sacrifice and self-denial, visions of “the good life” under Stalin were reoriented toward kul’turnost, “cultured living and consumption” (LeBlanc, 2016). Paintings and literature of abundance replaced the asceticism and scarcity of the War Communism years. This change in culture cast meat as a status symbol of “well-being and economic prosperity,” and was accompanied by significant investments making it more accessible (LeBlanc, 2016). From the early 1930s into the 1960s, most Soviet meat processing was done on-site at the collectivized farms with about thirty percent of slaughter taking place in urban, industrial meat facilities (American Federation of American Scientists, 1973). A modern processing facility was opened in Moscow in 1930, and in the years between 1932 and 1936, government production of meat nearly doubled (LeBlanc, 2016). Sausage production increased fourfold, from 36,000 tons to 170,000 tons. With an aim to cement new political values and celebrate this fantastic progress in meat production, the People’s Commissar of the Food Industry, Anastas Mikoyan, commissioned a politically suspect author, Boris Pilnyak, to write a Soviet Realist novel doing so. For Pilnyak, it was his shot at rehabilitation. During the 1930s, Soviet literature was an apparatus of state influence or, as Stalin put it, the “engineering of human souls” (LeBlanc, 2016). Pilnyak opposed this “social mandate,” calling it a castration, and had “slanderous” ideas about the regime of the 1920s. Describing the transition from tsarist horror to Soviet progress was his opportunity to atone for his opinions (LeBlanc, 2016). Contracted in 1935, Meat: A Novel, is similar to Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, about Chicago’s Union Stock Yards, and many horrors of the pre-revolutionary slaughterhouses are graphically similar. “Dogs urinate into bloody puddles.” Men are driven to theft and desperation, living in horrifying conditions and, “like the animals they slaughter,” suffering at the brink of starvation. Against this exploitation, the protagonist rallies toward socialist liberation, prompting efficient industrialization with human dignity and comfort. Despite its seeming alignment with Soviet values, the serialized novel was received as a tongue-and-cheek critique rather than a sincere fulfillment of the mandate. Three months after its publication in 1936, Meat was put on the list of “unacceptable” works. Within eighteen months, Pilnyak was arrested, convicted and executed, himself a victim of the totalitarian “meat grinder” that devoured so many literary artists during the Great Terror (LeBlanc, 2016). An important limitation on the quality and quantity of Soviet meat production was grain production. While the cropland of the USSR might have been about forty percent larger than cropland in the US, almost all of it lay north of Minnesota (Bell, 1961). High latitudes and vast distances from water created shorter, drier, and more severe growing conditions than the fertile prairies of middle America. Importantly, the infrastructure and labor force to work that land had been relatively sheltered during the first world war. Shielded from financial costs of rebuilding a devastated society, greater capital investment in agriculture also supported the US to outproduce the large collective and state-run farms of the USSR by about sixty percent by the 1950s (Bell, 1961). An investigation into why “agriculture, America’s biggest success, [was] communism’s biggest failure” was at the heart of another exchange of Soviet and US ideas under Khrushchev (Frese, 2004). Taking over at first secretary of the Communist Party after the death of Stalin 1953, Khrushchev had been born into a peasant family and raised sheep as a young man. In the Five-Year Plan of 1955-1960, he committed to an eight-fold increase in corn production and growing more grains for food animals. Khrushchev praised the “Corn Belt” of the United States in his well-publicized speech. This prompted an editorial in the Des Moines Register in February of 1955 inviting a Soviet delegation to Iowa, “to get the lowdown on raising high quality cattle, hogs, sheep and chickens.” The first exchange happened that summer, including a visit by Deputy Minister of Agriculture, Vladimir Matskevitch, to the largest “cutting edge” seed operation of its kind owned by Roswell Garst. Garst’s 5000 acre farm included, “hybrid seed corn, intensive use of nitrogen fertilizers, and cellulose-enriched cattle feed.” Notes about these developments were given to Khrushchev, who extended an invitation for Garst and his wife, Elizabeth, to visit the USSR that September. This led to the first Soviet order of 5000 tons of hybrid seed and permission from the State Department for Garst to export modern corn planters. Despite the many successful reforms that resulted from these exchanges, Khrushchev’s 1957 pledge to overtake US agricultural production was ultimately a failure, pushed through “with too few resources and inadequate infrastructure” (Frese, 2004). Growing food was one limitation of the Soviet agriculture system. Another limited was the amount of food lost in processing and transportation. Khrushchev had been replaced as first secretary by Brezhnev from 1965 until 1982, with quick succession of leadership until stabilizing with Gorbachev as first secretary in 1986. At the 27th CPSU Congress, Gorbachev said that harvest, transportation, storage and processing had such significant losses at each step that correcting each of them could increase the amount of food eaten by civilians by 20% (Gray, 1985). In terms of policy, this shifted financial commitment from farm production to greater investments in processing machinery. However, for all its focus on increasing consumption, per capita meat consumption in the USSR was double that of France or Belgium in the latter half of the 1970s. Although generally wealthier, the UK and Sweden only consumed 10 to 15% more meat than their Soviet counterparts (Gray, 1985). Slaughterhouse-1905: Meat Production in the United States In contrast to the collective farming of the obshchina and kolkhoz, farms in the U.S. before the 1950s were for the most part smaller and independently owned (USDA, 2024). The industrial processing of meat, however, was an early deviation from this model. Starting in Cincinnati in 1818, the first large-scale meat packing plant annually slaughtered 85,000 pigs by 1833 (Lisa, 2020). Cincinnati had been favored for this “Porkopolis” because of its transportation access and low-cost immigrant labor. With the first train shipment of cattle in 1867 and introduction of a practical refrigerated rail car in 1877, the slaughterhouse industry came to be concentrated in just a few cities (Lisa, 2020). In 1900, just five companies slaughtered about eighty percent of American cows (Carstensen, 1989). With more reliable markets for ranchers and industrial technology to increase efficiency, Americans in the early 20th century were able to access a greater variety and quality of meats while prices decreased relative to small town butchers who processed livestock on site (Cronon, 2009). Figure 1. Cattle at the Chicago Union Stockyards (Vachon, 1941). Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives The cost of this cheap abundance was filth and misery. The probable inspiration for Pilnyak’s Meat, Upton Sinclair’s 1905 novel, The Jungle, described these urban slaughterhouses as places of horrifying acts against people and animals. The newly introduced conveyor belt had mechanized slaughter into something “relentless, remorseless,” “pork-making by applied mathematics.” Places with “an odor so bad that a man could hardly bear to be in the room with them” and “wails of agony” so appalling, “one feared there was too much sound for the room to hold–that the walls must give way or the ceiling crack.” Visitors were brought to tears or nervous laughter. Laborers were often immigrants, men “hanging on the verge of starvation” who might work in one shop for thirty years, never save a penny, leave home at 6am and “come back at night too tired to take his clothes off” (Sinclair, 1905). If these working conditions sound familiar, it’s been suggested that animal slaughtering was the US’s first mass-production industry which inspired Henry Ford’s assembly-line that would reshape labor in the US and around the world (Fitzgerald, 2010). Figure 2. Untitled photos from a slaughterhouse in Pennsylvania (Dick, 1938ab). Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives “I aimed at the public’s heart, and by accident I hit it in the stomach.” Sinclair’s visceral description of men and pigs was an intentional critique of capitalist labor practices, but it was the descriptions of hygiene that prompted a public outcry (Francis, 2020). The rats were particularly compelling; “a man could run his hand over these piles of meat and sweep off handfuls of the dried dung” “…the packers would put poisoned bread out for them; they would die, and then rats, bread, and meat would go into the hoppers together.” The public demanded government intervention. After a Congressional investigation proved the novel’s claims well founded, the federal government passed two regulatory laws in 1906, the “Pure Food and Drug Act” and the “Meat Inspection Act” (Francis, 2020). Eventually leading to the formation of the Food and Drug Administration, these acts were a huge precedent for government intervention into the “private affairs” of business (Roots, 2001). Other state intervention into private agriculture arose in following decades. During World War I, farmers had been given favorable terms under the Federal Farm Loan Act of 1916 to grow food for the war economy (Metych, 2024). When overproduction dropped the price of a bushel of wheat from $1.02 in the early 1920s to $0.29 in 1932, farmers were unable to pay their mortgages and nearly 750,000 farms were foreclosed. To keep consumer prices low but farm income able to meet production expenses, Franklin Delano Roosevelt passed the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) as part of the New Deal in 1933. Paying farmers to voluntarily reduce their acreage or production, at least six million pigs were killed and ten million acres of cotton were destroyed (Metych, 2024). These interventions and their amendments, which would later be called the Farm Bill, extended into the 21st century and underpin a productivity and affordability that is not possible by market economics alone (Alizamir, Iravani, & Mamani, 2019). Other aspects of socialism in the US meat industry were fought more actively. Starting in the Great Depression of the 1930s, unionizing efforts achieved membership for 95% of northern slaughterhouse workers by the 1960s (Fitzgerald, 2010). These advances were not long held. After the 1973 OPEC oil embargo the price of beef and veal increased 65%, large companies dominating the industry began to actively change their practices toward cheaper meat production and higher profits (Hansen, 2023). Moving from the union-strong northern cities into the rural South, they also changed work processes to favor unskilled labor, shut down unionized factories, and intimidate on-going organizing efforts. By 1981, wages across the industry had fallen forty percent (Hansen, 2023). Alongside the “slaughter” of union wages, other commercial innovations would forever change American meat. The first industrialized grocery store, the Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company (A&P), opened in New York in 1912 (Hansen, 2023). Doing “for retailing what Henry Ford’s Model-T did for automobiles” (Ellickson, 2011), this new type of store only had one employee and allowed consumers to select from low-cost, pre-packaged products from multiple options (Levinson, 2011). This model would overtake fifty percent of US grocery market share by 1958, and nearly seventy percent in 1972 (Hansen, 2023). Prices were on-average lower at these stores, while suburbanization and American investment in roads favored parking-lot grocery stores over the specialized urban shopping that had been the destination for most meat products at the time of Upton Sinclair. The explosion of car culture also expanded the number and influence of fast food restaurants as major consumers of agricultural products. Together, the purchasing power of these two industries gave them unprecedented influence on the structure of US agriculture. A 2024 report by the Union of Concerned Scientists found that agribusiness, food and agricultural trade associations and other special interest groups spent more than $523 million dollars lobbying the Farm Bill (Negin, 2024). When overlaid on the history of the Cold War, this century of material abundance has been framed as a “triumph” or “victory” of capitalism and even given partial credit in the peaceful collapse of the Soviet Union. In his 2007 New York Times obituary, Boris Yeltsin’s visit to a Texan grocery store in 1990 is supposed to have left him overwhelmed at the “kaleidoscopic variety of meats and vegetables available to ordinary Americans” (Berger, 2007). According to biographer Leon Aron, the man who would become the first leader of the post-Soviet Russian Federation reflected after his visit, “I think we have committed a crime against our people by making their standard of living so incomparably lower than that of the Americans.” Figure 3. Boris Yeltsin in Randall’s Grocery, 1990. Copyright Paul Yirga. …And Meat Shall Make You Free: Values of Consumption …a man with his choice of a hundred kinds of salami is freer than one who only has ten to choose from. (Alexievich, 2016) A Russian observation after the fall of the Soviet Union, there’s both laughter and truth to this statement. A whole new field of values is required for the man with a hundred different kinds of salami. Consulting a former Di Bruno Brothers cheese monger, even these change depending on material conditions. Hors d’oeuvres? Try the fennel sweetness of Genoa. Frying it crispy? The “salty, smoky, richness of a hard salami would be ideal. For adding to scrambled eggs, the loose texture and slow brown sugar cure of a cotto would probably be my choice” (Gaffield, 2024). The man sensually distinguishing his preferences among deli meats is also distinguishing himself from the preferences and opinions of others. This sense of one’s uniqueness contributes to an increased sense of individualism (Realo et al, 2002). Although the term individualism has been used ‘in many different contexts and with an exceptional lack of precision’ (Lukes, 1971), its first definition in the Merriam-Webster Dictionary (n.d.) states, “the interests of the individual are or ought to be ethically paramount.” This prioritization of the individual aligns well with capitalist ideas about freedom but is a contrast to the Marxist collective endorsed by the Soviet Union. If there is only one type of salami (or none at all), no one can elevate themselves through exceptional taste in charcuterie. What’s suggested by this hundred-salami thesis is that a society providing greater abundance is also providing greater freedom. (It doesn’t consider the freedom of pigs, but there are other papers for that.) What Yeltsin called a crime was not depriving Soviet citizens of “regional Italian spices” and “slow air-curing,” but security, choice, sensuality, the capacity to enjoy and express oneself, to devote more time to living and less time to waiting in lines. Let them Eat Salami! Values of Production Deciding what society “ought” to do is called normative economics (Ancheta, 2023), and there are many different ways to assess society’s values for decision making (Dietz et al., 2005). US agricultural policy is increasingly considering the environment. In 2006, the global meat industry was estimated to produce between 15% and 24% of all greenhouse gas emissions (Steinfeld et al, 2006). There are about 213,000 Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) in the United States, and the amount of manure produced by these large operations can be seriously dangerous to humans and the environment if the nitrogen and phosphorous enter the local water systems in large quantities (Fitzgerald, 2010). There are “ethical,” emotional impacts to this industry as well. The worst thing, worse than the physical danger, is the emotional toll. …You may look a hog in the eye that’s walking around in the blood pit with you and think, ‘God, that really isn’t a bad-looking animal.’ You may want to pet it. Pigs down on the kill floor have come up to nuzzle me like a puppy. Two minutes later I had to kill them—beat them to death with a pipe. I can’t care (Eisnitz, 1997). Conclusion I used to think that top environmental problems were biodiversity loss, ecosystem collapse and climate change. I thought that thirty years of good science could address these problems. I was wrong. The top environmental problems are selfishness, greed and apathy, and to deal with these we need a cultural and spiritual transformation. And we scientists don’t know how to do that (Speth, 2016). I found myself thinking about the grotesque in so much abundance. A colleague who lived through the 1982 Lebanon War described coming back to America and experiencing what she would later learn was Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Her body, adapted to siege warfare, was physically sickened to enter a pet store and see how much food the United States devoted to “pets” (Murphy, M., 2015). A similar story is related in Sheryl WuDunn’s TEDtalk, “Our Century’s Greatest Injustice” (2010). She described an aid worker in Darfur who had maintained composure during all her witness of horror, and who finally broke down seeing something in her grandmother’s backyard: What that was was a bird feeder. And she realized that she had the great fortune to be born in a country where we take security for granted, where we not only can feed, clothe and house ourselves, but also provide for wild birds so they don’t go hungry in the winter. (WuDunn, 2010). I was born in that world. I have taken those things for granted. I have also been faced with a system so desperately violent and shameless that I am overwhelmed and reduced to paralysis in the face of it all. What is important as both environment and education verge on collapse? I set out on this research to discover by writing, a process I hope my students can one day practice; I learned, connected, saw gaps where I didn’t understand and thought about how my choices fit in to what I want for the world. “Ourselves we can change; others we can only love.”

Social Emotional Learning Only a Soviet can understand another Soviet (Alexievich, 2016). As I write, I am aware of my position as an American who has lived near-exclusively under some form of capitalism. Can I name the water I’m living in and encourage students to do so thoughtfully as well? I’m not a philosopher or anthropologist, so forgive any failures of grappling. I hope that asking students to discuss values, culture, and history will resonate with them emotionally, but it might do so in ways I don’t expect. That means taking special care to make sure cultures and feelings are respected as best as can be accomplished in the classroom. Social anxiety is at least as old as Hippocrates observations of shy men who would not leave their homes in 400 B.C.E. (Penn Psychiatry, n.d.), but its recent statistical increase is staggering. In 2022, the World Health Organization reported that anxiety and depression were up 25% globally after the COVID-19 pandemic compared with pre-pandemic levels (WHO, 2022). Among adolescents, findings are even more dramatic. In a longitudinal survey of 311 adolescent females conducted at Stoneybrook University, 49% reported “clinically elevated generalized anxiety during COVID-19” (Hawes et al., 2021). There have always been students who were comfortable interacting socially and others who experienced more anxiety around their peers. The pandemic has provided educators with encouragement from administrators to intentionally devote classroom time to lessons with social emotional support as the focus. Because feelings of connectedness are an essential driver of mental health, this may be critical for the well-being of students (Wickramaratne et al., 2022). The reverse is also true, that social anxiety contributes to young people’s ongoing perceptions of isolation. A 2007 study found that adolescents who experience higher levels of social anxiety are indeed treated more negatively by their peers (Blöte, 2007). For people with diagnosed Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD), it has been put forward that this feedback cycle contributes to maintaining the condition (Voncken & Dijk, 2013). Those same researchers, however, demonstrated that self-disclosure, or “how open one is about oneself to another person,” can increase likeability and thus reduce the experience of anxiety in social settings (Voncken & Dijk, 2013). In order for students to have meaningful discussions about the economic systems in their lives, they must feel comfortable participating in discussions. One strategy for achieving that comfort is to have students disclose personal information in a way that is considerate of young people who are increasingly more likely to experience social anxiety. In these activities, students are asked to learn about each other and vocabulary words through use of photographs on their phone highlighting “abundance” or “value” and a short explanation about why the photo matches the term. Total Participation Techniques Another way to support shy students is “total participation techniques.” Rather than asking for one volunteer to give an answer to a question or calling on names, this technique prompts the whole class to respond with nonverbal cues such as pointing, showing fingers, or raising a hand. This allows quick identification of who is not participating and possibly gives whole-class assessment of a simple concept. Sentence Stems Many students at my school are English Language Learners. One of the supports to help them organize content ideas while also exposing them to English grammar structures is the use of sentence stems, partially or mostly complete sentences that ask students to use word banks or independently generate words to finish the ideas (Polk, 2021). These can be combined to create small conversations to be shared aloud for speaking practice. Together, these activities practice the four key aspects of language acquisition: reading, writing, speaking, and listening.

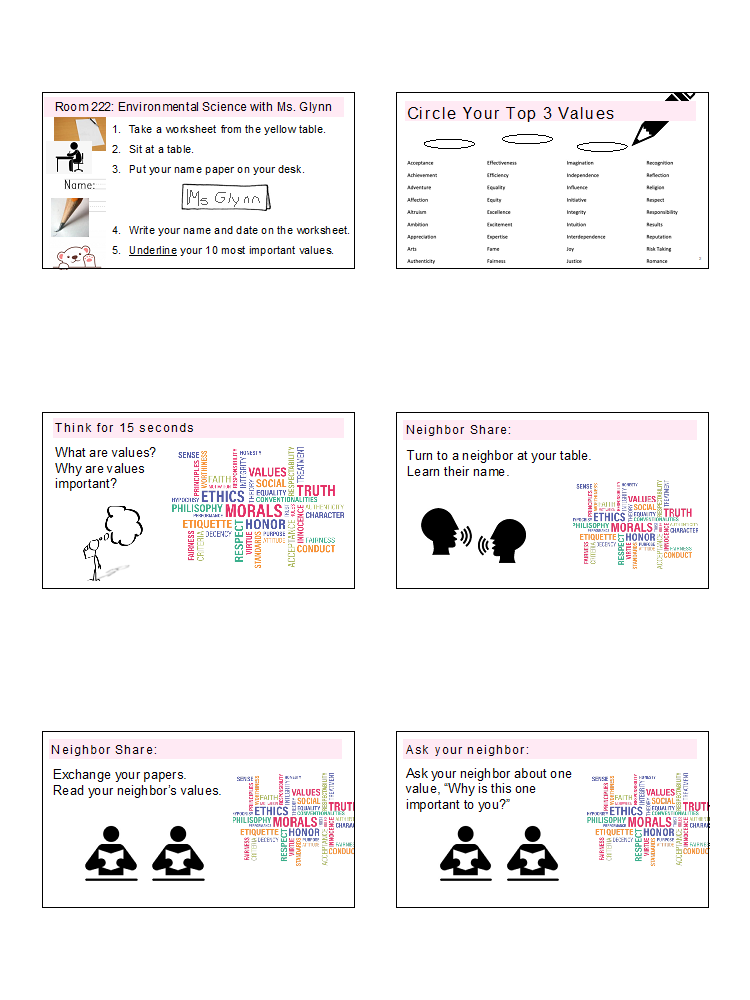

PA STEELS 3.4.9-12.H Design and evaluate solutions in which individuals and societies can promote stewardship in environmental quality and community well-being. At the beginning of the school year, students will be asked to identify their top ten guiding values, further identifying their top five, top three, and sharing them with classmates. Tables will then be asked to identify one value they think would help make a nicer classroom and to explain what actions students can do to realize that value. Working together, they will cut out the letters of that word and make banners to hang around our classroom so we can refer to them when students are making decisions that go against those values (see Appendix for value sheets and slides). Another activity for this standard introduces the idea of abundance as related to value system. After introducing the vocabulary word with pictures from my own life celebrating an abundance of friendship, food, and family, I will ask students to select one photo on their phone that represents “abundance” to them and to share that photo and story with a classmate. This serves as a basis for evaluating different aspects of decision making for the culminating activity. Common Core ELA W.8.3d Use precise words and phrases, relevant descriptive details, and sensory language to capture the action and convey experiences and events. On paper or digitally, students will listen to the audio of a pig on a slaughterhouse hook and describe what it sounds like. They will then read others’ writing and identify what made more or less emotionally compelling writing. After listening to the audio file, students will then be given images of “idyllic pastoral” farms and modern industrial agriculture and asked to describe both on paper. Once finished, they will be given a sheet of values and asked to assign five value words to each condition. Once collected, the descriptions of industrial agriculture will be “put into a hat” or some other method for students to randomly draw a paper. Because 99% of American meat is produced in the industrial system (Fox, 2023), there will be one “idyllic” description added to the hat. Once everyone has drawn a card, students will use a word cloud generator to highlight what values they think are optimized under that system. 3.5.6-8.FF Demonstrate how systems thinking involves considering relationships between every part, as well as how the systems interact with the environment in which it is used. When defined for my students, a system is a set of things working together. In environmental science, this includes physical science concepts like matter and energy, as well as human structures like government and culture. This activity builds on previous lessons about atoms, elements, macromolecules, food webs and food chains. Asking students to describe their favorite meals, they will be asked to find ingredient lists and identify which macromolecules make up three major ingredients. Then, they will look up one article and one video explaining industrial methods of growing those foods, whether animal or plant products. Revisiting the previous activity to identify the values that direct those systems, they will consult Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs as one guide for ranking values, then manipulate sentence stems and paper cut-outs with different values to identify what is more or less valuable for themselves.

ABC News. (2007, March 8). Saving the world, one plastic bag at a time. ABC News https://abcnews.go.com/Technology/story?id=2935417 Alexievich, S. (2016). Secondhand time: the last of the Soviets (First U.S. edition.). Random House. Applebaum, A. (2017). Red famine: Stalin’s war on Ukraine. Berger, M. (2007, April 23), Boris Yeltsin, Russia’s first post-Soviet leader, is dead. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2007/04/23/world/europe/23cnd- yeltsin.html Blöte, Anke & Westenberg, P. (2007). Socially anxious adolescents’ perception of treatment by classmates. Behaviour research and therapy. 45. 189-98. 10.1016/j.brat.2006.02.002. Collopy, E. (2005, June 4). The Communal Apartment in the Works of Irina Grekova and Nina Sadur. Journal of International Women’s Studies. vol. 6 Issue 2,. https://vc.bridgew.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1493&context=jiws Cozzi, L., Chen, O., Kim, H. (2023). The world’s top 1% of emitters produce over 1000times more CO2 than the bottom 1%. Wealth and carbon footprint. Energy Information Agency. https://www.iea.org/commentaries/the-world-s-top-1-of emitters-produce-over-1000-times-more-co2-than-the-bottom-1 Ellickson, Paul B., The Evolution of the Supermarket Industry: From A&P to Wal-Mart (April 1, 2011). Handbook on the Economics of Retail and Distribution, Chapter 15, Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, pp. 368-391, 2016., http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1814166 Eschel, G. & Martin, P. (2006). Diet, energy, and global warming. Earth Interactions. https://doi.org/10.1175/EI167.1 Federation of American Scientists. (1981, November). The Soviet Electric Power Industry. Technology and Soviet Energy Availability. ch. 5. https://www.princeton.edu/~ota/disk3/1981/8127/812707.PDF Fitzgerald, A. J. (2010). A Social History of the Slaughterhouse: From Inception to Contemporary Implications. Human Ecology Review. Vol. 17, No 1. https://humanecologyreview.org/pastissues/her171/Fitzgerald.pdf Frese, S. J. (2004, Nov). Comrade Khrushchev and Farmer Garst: East-West Encounters Foster Agricultural Exchange. The History Teacher: Society for History Education. Vol. 38, No. 1. pp. 37-65 https://www.jstor.org/stable/1555626 Gaffield, J. (2024, May 30). Personal communication. Goscilo, Helena. 2009. “Luxuriating in Lack: Plenitude and Consuming Happiness in Soviet Paintings and Posters, 1930– 1953.” In Petrified Utopia: Happiness Soviet Style, ed. Marina Balina and Evgeny Dobrenko, 53–78. New York: Anthem Press Gray, K. (1985). Soviet Utilization of Food: Focus on Meat and Dairy Processing. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Soviet Interview Project. Guerin, K. & McArthur, J. (2020, April 2). The Sounds of a Slaughterhouse. We Animals Media. https://weanimalsmedia.org/2020/04/02/the-sounds-of-a-slaughterhouse/ Hagerty, M., (2020, February 21). Houston Public Media. [IMG]. https://www.houstonpublicmedia.org/articles/shows/houston-matters/2020/02/21/361467/boris-yelstins-1989-visit-to-a-houston-grocery-store-is-now-an-opera/ Hansen, Randall, ‘What We Eat I: The Rise and Fall of Meatpacking Unions’, War, Work, and Want: How the OPEC Oil Crisis Caused Mass Migration and Revolution (New York, 2023; online edn, Oxford Academic, 24 Aug. 2023), https://doi-org.proxy.library.upenn.edu/10.1093/oso/9780197657690.003.0015, accessed 9 June 2024. Hawes MT, Szenczy AK, Klein DN, Hajcak G, Nelson BD. Increases in depression and anxiety symptoms in adolescents and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Med. 2022 Oct. 52(14): 3222-3230. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720005358. Hubbard, L. E. (1939). The Economics of Soviet Agriculture. Macmillan and Co. pp. 117–18. Joshi, I., Param, S., Gadre, M. (2015, November 10). Saving the Planet: The Market for Sustainable Meat Alternatives. Sutardja Center for Entrepreneurship and Technology. Berkeley Engineering. https://scet.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/CopyofFINALSavingThePlanetSustainableMeatAlternatives.pdf Karahashi, F. (2020). On the Cultic Aspect of the “Reforms of Urukagina”: Some Changes in the Festival of the Goddess Baba. Orient. vol. 55. https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/orient/55/0/55_63/_pdf/-char/en Kelloway, C. (2024, February 7). The Farm Bill Hall of Shame. Mother Jones. https://www.motherjones.com/food/2024/02/farm-bill-racism-black-farmers consolidation-crop-insurance/ LeBlanc, R. D. (2016, May 1). The Mikoyan Mini-Hamburger, or How the Socialist Realist Novel about the Soviet Meat Industry Was Created. Gastronomia 16(2): 31-44. doi.org/10.1525/gfc.2016.16.2.31 Levinson, M. (2011, August 23). How The A&P Changed The Way We Shop. Fresh Air. https://www.npr.org/2011/08/23/139761274/how-the-a-p-changed-the-way-we-shop Lisa, A. (2020, August 20). History of America’s Meat Processing Industry. Stacker. https://stacker.com/business-economy/history-americas-meat-processing-industry Lukes, S. (1971). The meanings of individualism. Journal of the History of Ideas. 32: 45–66 Marx, K. & Engels, F. (1848). The Communist Manifesto. Marxist Internet Archives. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1848/communist-manifesto/ Marx, K., Engels, F., Lenin, V. I., & Institut marksizma-leninizma (Moscow, Russia) (1970). Critique of the Gotha programme (E. Czobel, Ed.; A rev. translation). International Publishers. Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Individualism. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved June 2, 2024, from https://www.merriamwebster.com/dictionary/individualism Metych, M. (2024, May 8). Agricultural Adjustment Act. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Agricultural-Adjustment-Act Negin, (2024, May 14). Ask a Scientist: Stopping Big Ag from Hijacking US Farm and Food Policy. The Equation. Union of Concerned Scientists. https://blog.ucsusa.org/elliott-negin/ask-a-scientist-stopping-big-ag-from-hijacking-us-farm-and-food-policy/ Painter, K. (2024, April 30). Personal communication. Penn Psychiatry Center for the Treatment and Study of Anxiety. (n.d.) Social Anxiety Disorder. https://www.med.upenn.edu/ctsa/social_anxiety_symptoms.html Pennsylvania Department of Education (n.d.). “Pennsylvania’s Science, Technology, Engineering, Environmental Literacy & Sustainability Standards” https://www.education.pa.gov/Teachers%20%20Administrators/Curriculum/Science/Pages/Science-Standards.aspx Polk, M. (2021, January 25). The Power of Sentence Stems. The Literacy Dive Podcast. https://theliteracydive.com/podcast-episode15/ Realo, A., Koido, K. Ceulemans, E. & Allik, J. (2002). Three Components of Individualism. European Journal of Personality. online. 16: pg. 163-184. doi:10.1002/per.437. https://journals-sagepub- com.proxy.library.upenn.edu/doi/epdf/10.1002/per.437 Roots, Roger I. (2001) “A Muckraker’s Aftermath: The Jungle of Meat-packing Regulation after a Century,” William Mitchell Law Review: Vol. 27: Iss. 4, Article 1. Available at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr/vol27/iss4/1 Roudik, P. (2013, January 8). Treaty on the Creation of the Soviet Union- Signed, Sealed, Delivered? Library of Congress Blogs. Law Library of Congress. https://blogs.loc.gov/law/2013/01/treaty-on-the-creation-of-the-soviet-union- signed-sealed-and-delivered/ Russopedia. (n.d.). Avoska. RT.com. https://russiapedia.rt.com/of-russian origin/avoska/index.html Siegelbaum, L. (n.d.). The Kruschev Slums. 17 Moments in Soviet History. https://soviethistory.msu.edu/1961-2/the-khrushchev-slums/ Speth, G. (2016). “We scientists don’t know how to do that” ……what a commentary! Wine and Water Watch. https://winewaterwatch.org/2016/05/we-scientists-dont-know-how-to-do-that-what-a-commentary/ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. (2020, December 21) Karl Marx. Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/marx/ UN Environment Programme (2021, December 20). From birth to ban: a history of the plastic shopping bag. https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/birth-ban-history-plastic-shopping-bag USDA. (2024, February 29). The number of US farms continues slow decline. United States Department of Agriculture: Economic Research Services. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/chart-gallery/gallery/chart-detail/?chartId=58268 Wickramaratne PJ, Yangchen T, Lepow L, Patra BG, Glicksburg B, Talati A, Adekkanattu P, Ryu E, Biernacka JM, Charney A, Mann JJ, Pathak J, Olfson M, Weissman MM. Social connectedness as a determinant of mental health: A scoping review. PLoS One. 2022 Oct 13;17(10):e0275004. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0275004. PMID: 36228007; PMCID: PMC9560615. World Health Organization (2022, March 2). COVID-19 pandemic triggers 25% increase in prevalence of anxiety and depression worldwide. https://www.who.int/news/item/02-03-2022-covid-19-pandemic-triggers-25-increase-in-prevalence-of-anxiety-and-depression-worldwide Yuko, E. (2021, November 18). How the Industrial Revolution Fueled the Growth of Cities. History.com. https://www.history.com/news/industrial-revolution-cities

Since 2002, the School District of Philadelphia environmental science curriculum has been guided by relevant content areas in the Pennsylvania Keystone Biology Anchors. Effective June 30th, 2025, those standards will be replaced by the Pennsylvania Science, Technology, Engineering, Environmental Literacy & Sustainability standards (STEELS)(Department of Education, n.d.). PA STEELS Standards: 3.4.9-12.H Design and evaluate solutions in which individuals and societies can promote stewardship in environmental quality and community well-being. 3.5.6-8.FF Demonstrate how systems thinking involves considering relationships between every part, as well as how the systems interact with the environment in which it is used. Common Core ELA W.8.3d Use precise words and phrases, relevant descriptive details, and sensory language to capture the action and convey experiences and events. Name: Date: 3. Draw a circle (◯) for your 5 most important values. 4. Draw a star (☆) for your 3 most important values 5. Choose one thing to write about: a. How do you feel when you help someone? b. Write about someone who has good values. c. Choose one value. How does a student act if they have that value? d. Write about a time you did not live up to your values. ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ Aceptación Eficacia Imaginación Reconocimiento Logro Eficiencia Independencia Reflexión Aventura Igualdad Influencia Religión Afecto Equidad Iniciativa Respeto Altruismo Excelencia Integridad Responsabilidad Ambición Excitación Intuición Resultados Apreciación Pericia Interdependencia Reputación Letras Fama Alegría Tomar riesgos Autenticidad Justicia Romance Autoridad Fe Amabilidad Autoexpresión Autonomía Familia Conocimiento Respeto a ti mismo Balance Flexibilidad Liderazgo Servicio Belleza Enfocar Lealtad Intercambio Pertenencia Perdón Hacer una diferencia Soledad Cariñoso Libertad Trabajo significativo Espiritualidad Celebracion Amistad Consciencia Éxito Desafío Divertido Naturaleza Apoyo Elección Objetivos Criando Trabajo en equipo Colaboración Gratitud Orden Tiempo Compromiso Crecimiento Pasión Tolerancia Comunidad Felicidad Paz Unión Comunicación Salud Crecimiento personal Tradición Compasión Ayudando a otros Perserverancia Viajar Conexión Altas expectativas Desarrollo personal Confianza Contribución Honestidad Placer Verdad Cooperación Esperanza Actitud positiva Unidad Creatividad Humildad Orgullo Variedad Democracia Humor Productividad Ánimo Editable Google slides available here: https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1ov4UuD5_A8j-a-7qdJVDXp-Mfx0g80Lv3wWyAotVxjE/edit?usp=sharing\